The road to resilience

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of Coastwatch magazine, published by North Carolina Sea Grant.

Durwood Stephenson’s cell phone lit up with calls when Hurricane Matthew battered North Carolina in October 2016. As the director of the U.S. Highway 70 Corridor Commission, he was a go-to for eastern North Carolinians worried about road conditions.

For example, a caller in New Bern who had encountered flooding on U.S. 70 lamented, “I don’t know where to go or how to go. What do I do?” The driver was en route to Goldsboro to pick up his mother and take her to the hospital. “I suggested he call 911 in Wayne County,” Stephenson says.

Matthew caused more than 1,760 road closures in the state, according to the North Carolina Department of Transportation Statewide Operations Center. A section of Interstate 40 in Johnston County was shut down for a week, while portions of Interstate 95 in Robeson and Cumberland counties were closed for 10 days. The storm’s costliest impacts stemmed from river flooding in eastern North Carolina, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information. The state hadn’t seen such devastation from inland flooding since 1999, with Hurricane Floyd.

“Matthew made it popular again in eastern North Carolina to start thinking about flood mitigation,” Stephenson says. “It flooded everything east of Raleigh, all the way to the coast. Smithfield was not passable; I couldn’t get to my office, and I don’t live but five or six miles away.”

North Carolina was still recovering from Matthew when Hurricane Florence arrived in 2018. Its drenching rains caused rivers to overtop their banks, crushing many previous record flood heights. The storm caused more than 2,500 road closures, again including sections of Interstates 95 and 40.

Short-term closures occurred because of standing water and overtopping from streams. Meanwhile, road washouts that required repairs or complete reconstruction forced long-term closures. Hurricanes Floyd, Matthew, and Florence together cost the state tens of billions of dollars, mainly because of damages from major flooding in the Neuse, Cape Fear, Lumber, Cashie, and Tar-Pamlico river basins of the Coastal Plain.

As the climate warms, North Carolinians can likely expect more frequent and severe inland flooding, fueled by more frequent, intense precipitation, according to the North Carolina Climate Science Report, released this past March by the North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies.

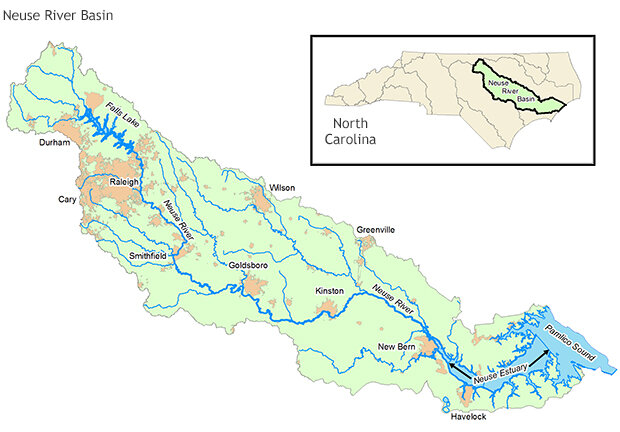

To better understand transportation-related impacts and other problems associated with Coastal Plain flooding, North Carolina Sea Grant and NC State University’s Biological & Agricultural Engineering Department collaborated with the N.C. Department of Transportation (NCDOT), N.C. Emergency Management (NCEM), and local governments on a multifaceted study now wrapping up. The team also investigated potential mitigation strategies. Their research centered on three municipalities in the Neuse River basin: Smithfield, Goldsboro, and Kinston.

The Neuse River flows from the North Carolina Piedmont to the Coastal Plain, where it empties into Pamlico Sound. Map by Lower Neuse River Basin Association.

“They had suffered a lot in the last couple floods,” says NCDOT’s LeiLani Paugh of the communities. “They had reached out to DOT, they had reached out to other officials.”

Stephenson, a self-described “eastern North Carolina boy,” is an active community member. “I’ve been interested in and concerned about the flood issue for a long time,” he says. “It is a major problem for eastern North Carolina.”

Lay of the land

The Neuse River begins at Falls Lake Reservoir Dam in the Piedmont and empties more than 200 miles later into Pamlico Sound. Its course traces rolling hills and eroded valleys that transition to sand hills and more level land at a geographic feature known as the fall line, or fall zone.

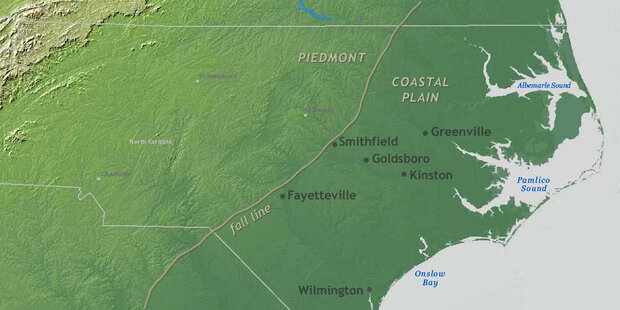

The fall line in North Carolina separates the Piedmont from the Coastal Plain. East of the line, there is little high ground, and many cities and towns sit in or next to the floodplains of the region's many rivers. NOAA Climate.gov image, adapted from digital elevation model data from NOAA NCEI's bathymetric data viewer.

“As soon as you get in the Coastal Plain, there’s really not a lot of relief to speak of,” says Jonathan Page, a hydraulic engineer who was part of the study team. In rivers, the fall line manifests as rapids, which prevent boats from navigating farther upstream. As North Carolina developed, the fall line significantly affected where people settled, according to the Encyclopedia of North Carolina. “The fall line was a first frontier,” wrote the journalist T. Edward Nickens for Our State in 2016. “The river shallows made for convenient crossings — first for Native Americans, and then for settlers, and later for bridges that carried cars across the rivers. It was the place where towns were planted.”

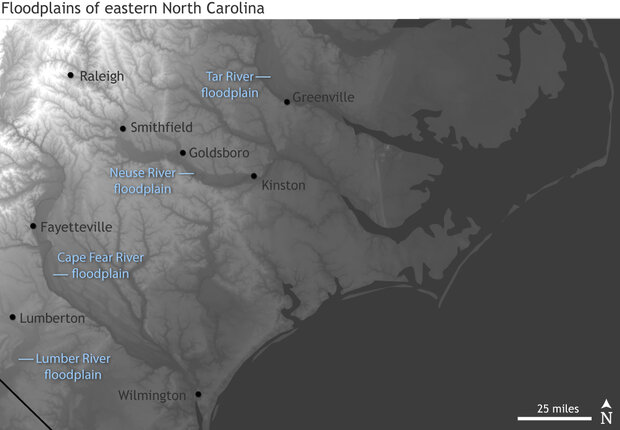

A digital elevation map of North Carolina shows the higher elevations (white) and narrower stream channels of the Piedmont part of the state and the nearly flat terrain of the Coastal Plain with its numerous broad floodplains (dark gray). Many cities sit within their adjacent river's floodplain. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on data from the USGS.

As it flows eastward from the fall line, the Neuse flattens, and the floodplain significantly widens. By virtue of their location, parts of Smithfield, Goldsboro, and Kinston exist in that floodplain. As many North Carolinians know all too well, flooding imperils life, health, and livelihoods, in part because it can debilitate transportation infrastructure.

“Road closures — especially extended road closures, when the road is completely washed away — have big impacts,” says Barbara Doll, an extension specialist with North Carolina Sea Grant and NC State faculty member, who led the study.

Washout on NC Highway 210 at Moore's Creek on October 1, 2018, following Hurricane Florence. NOAA photo by Carl Morgan, National Weather Service.

To kick off their project in 2018, Doll’s team first needed to familiarize themselves with how land use and land cover have evolved over time in each study area. They asked questions such as, What’s the soil like? How have rainfall patterns changed? To develop a detailed picture, the researchers used geospatial data; historical precipitation and discharge records; satellite imagery; soil surveys; and topographic data.

Then they hosted stakeholder meetings in Smithfield, Goldsboro, and Kinston. At each workshop, they invited local officials, emergency responders, utility operators, and other specialists to identify locations where they were concerned about flooding, with a focus on the transportation network. Doll’s team also shared what they had learned in their background research.

“It really provided a unique opportunity to say, ‘Hey, here’s what we’re seeing from all of the information, data, that we’ve gathered; give us your thoughts and feedback,’” Page says.

That stakeholder feedback informed the scope of the study. “We really let what they said in those meetings drive a lot of what we did,” Doll says.

Over the river

During the workshops, stakeholders expressed concerns that various bridges were contributing to flooding in their municipalities. More than 10 road, highway, and railroad bridges straddle the Neuse River between Smithfield and Kinston. Those bridges have embankments to elevate the road surface across the floodplain leading up to the river channel. Embankments obstruct water flow on the floodplain. During an extreme event such as a hurricane, it’s possible that embankments create a backwater effect that potentially exacerbates upstream flooding.

Doll’s team decided to investigate the influence of bridges on water surface elevation using hydraulic modeling, a computational way of predicting flooding based on different scenarios. What if bridge span or elevation were increased, or an embankment were removed?

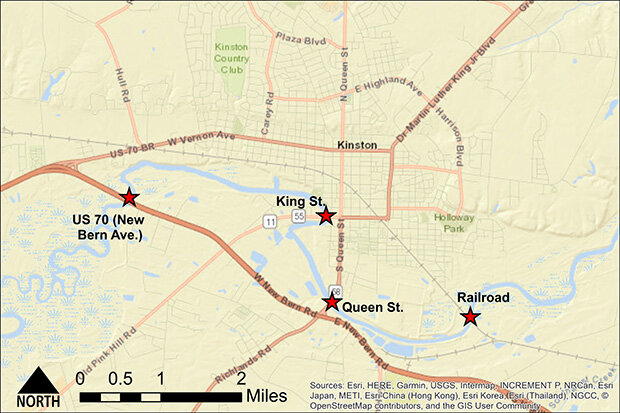

Based on residents' concerns, researchers modeled how modifications to three road bridges and a railroad bridge (red stars) in the Kinston area would affect upstream flooding. Map by N.C. Sea Grant/NC State University Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering.

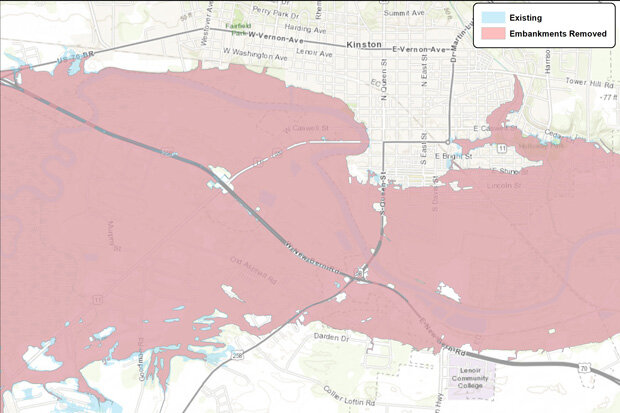

In Smithfield, they studied U.S. 301 and I-95 bridges and a railroad bridge. Near Goldsboro, they focused on the Arrington Bridge Road crossing. And in Kinston, they examined bridges along U.S. 70 (also called New Bern Avenue), King Street, Queen Street, and a railroad southeast of town.

Through modeling, they experimented with modifying one bridge or multiple in tandem. In Goldsboro and Kinston, they also tried removing bridges entirely. Overall, modeling suggested that substantially altering bridges would have minimal impact on upstream flooding. For most of the bridge modification scenarios, the change in water surface upstream was less than a foot, and often less than half of a foot for a storm like Matthew.

Flooding (pink) during a Matthew-scale event if the U.S. 70, King Street, and Queen Street bridges were modified. The extent is only slightly less than the flooding that would occur under existing conditions (blue). North Carolina Sea Grant/NC State University Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering.

“We saw that investing millions and millions of dollars in increasing the spans of those bridges provided limited flood reduction benefits upstream,” says Jack Kurki-Fox, a team member who worked on the hydraulic modeling. “This money could be better spent on strategic transportation infrastructure upgrades and moving people out of flood-prone areas through buyouts, especially given the likelihood of more extreme events in the future.”

In many of the modeling scenarios, the primary reason bridge modification had limited advantages appears to stem from the very nature of the surrounding environment. Because the Coastal Plain gradually slopes toward the sea, rising floodwaters move sluggishly eastward. The resulting backwater eclipses any limited relief on upstream flooding from bridge modification, according to Doll.

“In many areas, the river itself is a relatively small channel when compared to its wide floodplain,” Doll says. “During these huge flows, the water is already spread way out onto the floodplain downstream of the bridges. So, even if the bridges were modified, the flow is blocked by all the water that is pooled downstream.”

Beyond bridges

Smithfield, Goldsboro, and Kinston also reported severe flash flooding along tributary creeks to the Neuse River. In many cases the flooding — which often occurs much earlier than when the river crests — forces road closures and restricts access to important areas of town. As the river discharge peaks, it creates backwater that floods the creeks again.

Doll’s team inventoried culverts and bridges along all tributaries that experience flash flooding that had been identified by stakeholders. Their aim was to determine if any updates could alleviate flooding. They found that most structures were in decent condition. To have any effect on flood mitigation, costly modifications—namely, raising roads—would be necessary.

U.S. Highway 70 in Kinston, NC, in September 2018. The road was among the hundreds of roads closed in North Carolina due to flooding or damage from heavy rain during Hurricane Florence. Photo by NC Department of Transportation.

Another common concern in all three municipalities was that development upstream in and around Raleigh has worsened flooding in their communities during large rain events. As the thinking goes, more impervious surfaces cause greater amounts of runoff that eventually wends its way downstream.

The team found through modeling that development near the state capital isn’t a major culprit. A large rain event in the Neuse River basin will create runoff regardless of where the precipitation falls.

“If you get 10 to 15 inches of rain covering a large portion of the watershed, it runs off of everything, especially when the ground is already wet. It doesn’t have to fall on the pavement and developed areas of Raleigh,” says Dan Line, who modeled watershed hydrology for the study. “In fact, much of the rain during Hurricane Matthew fell on Johnston County and areas southeast of Raleigh.”

Line also investigated how future urban sprawl south and east of Raleigh might contribute to downstream flooding. His modeling showed that continued build-out would result in only a moderate rise in peak flow. Indeed, most of that area is farmland, which already generates substantial runoff when fully saturated.

Falls Lake Reservoir, which in part provides drinking water to the City of Raleigh, was a hot topic as well. The team confirmed that the water body doesn’t contribute to downstream flooding, however. In fact, says hydraulic engineer Jonathan Page, “the primary purpose and overwhelming majority of the storage within the lake is used for flood control.”

Alternate routes

The very fact that Smithfield, Goldsboro, and Kinston lie along a floodplain makes a degree of flooding inevitable. And the problem will likely get worse.

For example, Doll’s team also looked at the effect of future storms on Neuse River flooding. Using climate data from the United States Environmental Protection Agency and assistance from the Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center, they found that, under warmer conditions, another hurricane like Matthew would produce more rainfall, resulting in flooding of greater extent and depth along the river.

As Doll’s study suggests, certain infrastructure updates, such as modifying bridges, would have virtually no effect on alleviating flooding, while other upgrades, like raising roads, are cost- and technically prohibitive. Short of moving whole communities to higher ground, what other options exist?

“We can’t just leave people hanging,” Paugh of NC DOT says.

There are various strategies to consider. For instance, early warning systems that indicate when important routes will flood could prove vital to steering people away from dangerous streets. For their part, Doll’s team investigated locations where new stream gauges could be installed as part of an early-warning network.

Analysis indicates that the state can't possibly afford to move all roadways out of the floodplain. But more sophisticated monitoring could provide early warning of flooded roads—such as this section of I-40 near Wallace, NC, that flooded during Hurricane Florence in September 2018—that would increase safety. Photo by North Carolina Department of Transportation. Used under a Creative Commons license.

In response to prolonged closures of important thoroughfares, the concept of “resilient routes” also has emerged. Instead of attempting to fix all roads, so the idea goes, attention should be on identifying critical transportation routes that experience minimal flooding, and then upgrading them to withstand extreme events, such as 500-year or 1,000-year floods.

“We can’t pick every road up out of the floodway,” Paugh says. “What are those safe routes, and can we make those more resilient?” Such a network would provide access to important areas, such as hospitals, during extreme flooding, as well as enable emergency response, evacuations, and supply delivery.

“It’s not going to prevent flooding,” Page says, “but it is going to maintain access and continue to allow those emergency services to occur.”

Finally, one relatively simple approach to minimize damage from flooding is to curb development in susceptible areas. For example, an earlier study commissioned by NCEM found that from 2001 to 2016, development in the 100-year floodplain increased by an average of 17% in Smithfield, Goldsboro, and Kinston.

To help those communities plan better, Doll’s team enlisted researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to review floodplain ordinances across the country in order to make recommendations to the municipalities on how to modify their own language.

Ultimately, Doll’s study is one element of a larger, ongoing effort by partners such as NC DOT to address resilience in the face of climate change. “It’s not just an engineering issue, it’s not just an environmental or a natural resource issue. The impacts, the problems, and the solutions all have multidisciplinary components,” Paugh says.

“That study is not necessarily the end — it’s maybe the beginning of additional studies and collaboration,” adds Stephen Morgan, the state hydraulics engineer for NC DOT. “I think through that process we will continue being a leader in forward-thinking approaches to our most challenging problems.”

For more information on the Neuse River flood mitigation study, and for details on improving resilience to flooding, go to go.ncsu.edu/flood-mitigation.

Original Editor's note: This article relies in large part on summaries and reports written by Jack Kurki-Fox, Dan Line, and Barbara Doll.