Strawberry growers reap profits with less spray, more science

A healthy strawberry on the vine at Ferris Farms, a central Florida strawberry farm managed by Dudley Calfee. Photo courtesy the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

The Florida morning was cool and damp; raindrops from a predawn shower shone on the strawberry leaves like little cabochon diamonds. Dudley Calfee, surveying his strawberry crop, knew that if the weather warmed up before the raindrops dried fruit rot could get a hold and, instead of gleaming red berries to bring to market, he would have a moldy grey fuzz of a disaster on his hands.

The subtropical climate of Florida makes growing strawberries a constant battle against at least two kinds of fruit rot: Anthracnose and Botrytis. Traditionally, Florida strawberry farmers have sprayed fungicide to prevent rot. They sprayed every week or ten days throughout the growing season, just in case rot was even thinking of appearing. The costs of spraying—including fungicides, equipment, and personnel—cut into profits, and also gave Florida strawberries a reputation that doesn’t square with customers’ demand for more natural berries.

Strawberry farmers in Florida fight against fruit rot, two of the most common forms being Anthracnose (left) and Botrytis (right). Photo courtesy the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Calfee himself used to be a spray-every-week farmer. Then one day he got a call from Natalia Peres, a plant disease scientist with the Gulf Coast Research and Education Center at the University of Florida. Funded by the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Peres and her team were researching strawberry disease, and they were wondering if Calfee would be willing to be a guinea pig. They wanted to test a system to allow growers to raise strawberries with less fungicide. The system they had developed used an algorithm to process temperature data, leaf wetness readings, humidity, and the local weather forecast together to tell if conditions would be favorable for fruit rot fungus to grow. Using the algorithm, their system would predict whether spraying with fungicide was necessary.

Peres and her team proposed to tell Calfee when to spray fungicide and when to hold off. She asked him to promise not to spray unless they said so. If the system was successful he could cut fungicide sprays by 50 percent while keeping berry yields the same, Peres predicted. If she was right, Calfee would save both time and money and end up with a strawberry yield as good as if he had sprayed every week.

Farmer Dudley Calfee and Dr. Natalia Peres, a plant diseases scientist with the University of Florida’s Gulf Coast Research and Education Center, check sensors on the farm. These sensors process temperature data, leaf wetness readings, humidity, and local weather forecasts. Photo courtesy the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Calfee was skeptical. In fact, there was no way he would trust his berry crop to some scientist. On the other hand, he wanted to find out if she was right. So he agreed to run Peres’ test on a quarter-acre plot—just nine strawberry beds for one season. He agreed to spray that one area only when told. To be safe, Calfee carefully placed his test plot where it wouldn’t contaminate the rest of the crop if it went to rot.

The first year Calfee was pretty impressed. The test plot grew no more Anthracnose and Botrytis fungus than the rest of his crop, though he sprayed it about 30% less than the surrounding fields. Still, he remained skeptical. Perhaps the test plot was protected by the 82 regularly sprayed acres of berries around it. The next year he agreed to quadruple the test area to an acre. Again the results were the same on the science-advised plot as on the fields he sprayed weekly. Sometimes a bit of the fungus would start to show, but if the weather was too cool or dry for it to thrive, it would clear up on its own.

A hazy morning in a central Floridian field. The high humidity associated with central Florida’s subtropical climate means that farmers constantly battle against fruit rot. Photo courtesy Traveling Crab Photography.

The third year, Calfee managed five of his 83 acres by following the Strawberry Advisory System, informed by Peres and her team. The system worked! By the fifth year, Peres had to convince Calfee to keep spraying one quarter-acre test plot weekly as a control in their experiment. He only sprayed the rest of his 83 acres when the science team sent him an alert. “We believed it after we watched it with our own eyes,” he said.

Florida farmers grow about 11,000 acres of strawberries. Peres’ team estimates that spraying only when needed, and spraying the best product for the problem, can save up to $400 per acre per year. If all growers in Central Florida used the system for their 7,500 acres of winter strawberries, they could reduce their costs by up to $3 million per year.

A farmer sprays a strawberry field with pesticides. Photo courtesy Mark Bolda, University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

Calfee says that, in addition to saving money, he appreciates that he can now say he grows strawberries that are as close to organic as possible in Florida—a claim he knows his customers appreciate. There was quite a bit of reluctance among neighboring farmers at first, but after five years word spread about the success of the system. Just over half of strawberry growers in Florida have adopted the Strawberry Advisory System in its first decade of existence, reducing their use of fungicides by 30-50%. That’s a good adoption rate, notes Peres, adding that less spraying also helps the fungus avoid developing resistance to the chemicals.

That damp fall morning, another farmer might have called in his sprayers, but Calfee chose to trust in science. He checked his phone. No alerts from the Strawberry Advisory System; the weather was expected to stay too cool for fruit rot to thrive. These days, he is confident that if the Advisory System doesn’t send an alert, his strawberries will be safe without spraying.

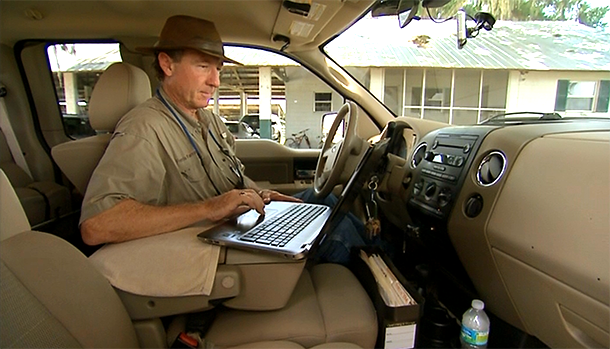

Dudley Calfee checks the Southeast Climate Consortium website for Strawberry Advisory System alerts. The system provides recommendations for timing fungicide applications. Photo courtesy the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Dudley Calfee has become chairman of the research committee of the Florida Strawberry Growers’ Association. Last year the association invested nearly $1 million in research for what Calfee calls “increasing precision agriculture to optimize yields.” And Calfee won the prestigious Commissioner’s Agricultural Environmental Leadership Award. The award site says, “Dudley Calfee has emerged as an authority in utilizing environmental programs, technologies, and best management practices to preserve our land while producing quality crops.”

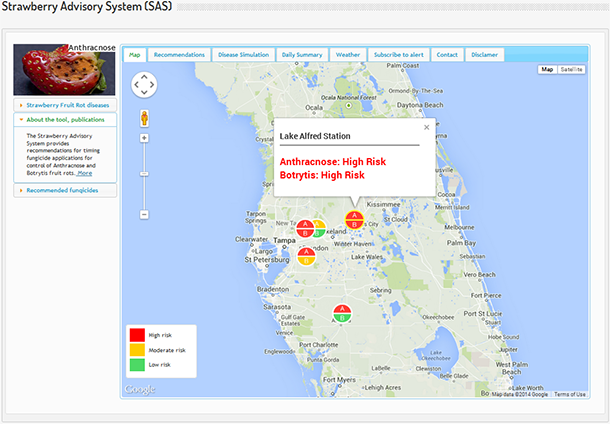

The Strawberry Advisory System provides farmers with color-coded fungicide application recommendations from their nearest weather station. Green indicates that crops are at low risk, yellow indicates moderate risk, and red indicates high risk. Courtesy the Southeast Climate Consortium.

Peres’ Strawberry Advisory System is part of a suite of online tools known as AgroClimate. Funded in part by NOAA’s Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments (RISA), AgroClimate is a climate forecast and decision-support system for farmers in the Southeast.

Today, Peres’ team is looking to collaborate with berry farmers in other states while also expanding to the next challenge: blueberries.

Links

AgroClimate Strawberry Advisory System