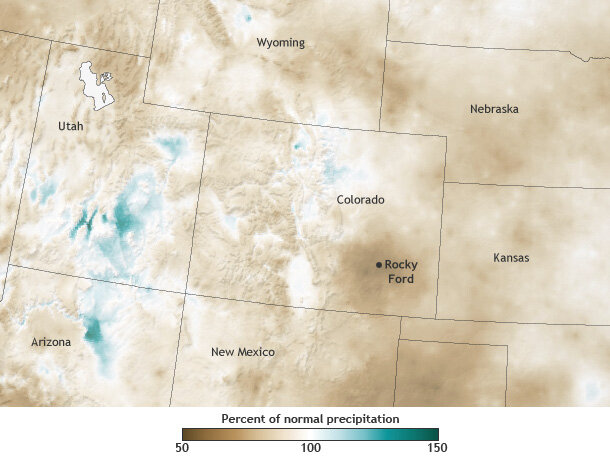

Before severe flooding struck Boulder, Colorado, and the surrounding area in September 2013, abnormally dry or drought conditions enveloped almost the entire state. The southeastern corner of the state was particularly parched. September rains eased the drought's grip over a large portion of north-central Colorado, including much of the heavily populated Front Range. But even after that historic rainfall, the plains of southeastern Colorado remained deep in drought.

Percent of normal precipitation for July 2011-December 2013 as compared to the 1981-2010 average. Map by NOAA Climate.gov, based on PRISM data. Data from most recent 6 months are provisional.

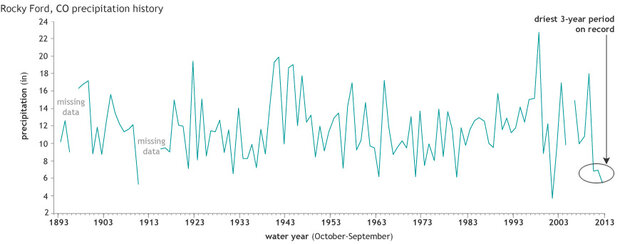

Colorado State Climatologist Nolan Doesken explained that drought conditions descended on southeastern Colorado in the autumn of 2010, with the driest conditions occurring in May and June of 2013. The worst-affected area was Rocky Ford, a community roughly 50 miles east-southeast of the city of Pueblo. Over the late summer of 2013, Doesken said, "rainfall improved—one storm at a time—in surrounding areas, but not in the immediate vicinity of Rocky Ford."

Doesken wasn't surprised by Rocky Ford's relative aridity. It has often been the driest part of southeastern Colorado, and in 2013, the region was "disproportionately drier than all regions around it." September 9-15, 2013—the week that brought rains to Boulder that some people characterized as "biblical"—had a modest effect on Rocky Ford's persistent dryness. The area received only about a half inch of rain.

Precipitation in Rocky Ford, Colorado, for "water years"—October-September periods—since 1893. Although precipitation in 2002 was also quite low, the past three years are the driest consecutive 3-year period on record. Graph by NOAA.Climate.gov, based on data provided by Wendy Ryan.

And after the flooding stopped, southeastern Colorado remained stuck in persistent drought. Although the heavy rains elsewhere in the state deposited more water into the nearby Arkansas River, "only the irrigated areas saw improvement" in southeastern Colorado, Doesken said. Only a few days after the rains, dust storms strong enough to force local road closures struck the region.

Dust storm brewing over the plains of eastern Colorado near Keota on March 17, 2013. Photo © Alan Szalwinski. Used with permission.

A history of dryness and drought

Dryness and drought are no strangers to this region. From 1981 through 2010, average annual precipitation for southeastern Colorado was between roughly 10 and 16 inches. (For comparison, some parts of northern California received well over 60 inches per year during the same period.)

Further, southeastern Colorado experienced some of the most severe effects of the 1930s Dust Bowl, and even the worst droughts documented in the historical record don't compare to the megadroughts that affected North America between the 10th and 15th centuries. Tree-ring data and archaeological evidence suggest that some of those droughts lasted decades.

Future of drought

Given the natural climate’s tendency toward drought, it's reasonable to wonder whether droughts in southeastern Colorado will worsen in a warming climate. But that question is not easy to answer.

For one thing, terrain has a large influence on climate conditions. Stretching over more than 100,000 square miles, Colorado is the eighth-largest U.S. state. It ranges in elevation from 3,315 to more than 14,000 feet above sea level, and it encompasses a wide variety of landscapes with differing precipitation patterns: conifer forest, alpine tundra, grassland, and high desert. Each may respond to climate change in different ways.

In addition, Colorado lies along a boundary between areas projected to receive more precipitation and areas expected to receive less precipitation in the coming decades. A 2008 report for the Colorado Water Conservation Board pointed out that, while climate models indicate a temperature increase of about 4°F by 2050, individual model projections show poor agreement about whether the state's annual mean precipitation will rise or drop by the same year.

Whether drought will be worse remains uncertain, but meteorologists, climatologists, and water managers agree that drought and southeastern Colorado are likely to remain on familiar terms for decades to come.

In near-term, little improvement expected

As for southeastern Colorado, Doesken doubted the region would emerge from its current dry conditions for months. In early November 2013, he stated, "The area typically only averages about 1 inch of precipitation from now until the first of March, and the three-year deficit for the region is about 15 inches or so."

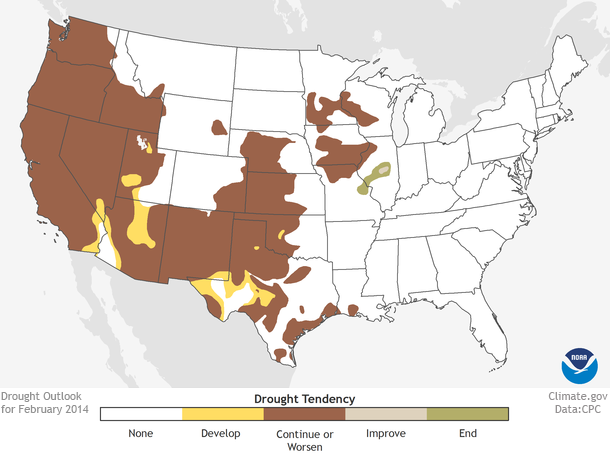

True to Doeskin's predictions, drought conditions didn't budge from southeastern Colorado for months after the September floods. Through the end of 2013 and into early 2014, the U.S. Drought Monitor showed dry conditions lingering in that quadrant of the state, including a persistent area of exceptional drought. NOAA’s drought outlook for February included southeastern Colorado in the area where drought was likely to continue or worsen.

Drought outlook for February 2014, based on data provided by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

According to Doesken, the region did get a small break early in the month, when a couple of wet snows finally settled major dust storms, at least temporarily.

References

Center for Air Pollution Impact & Trend Analysis. (n.d.). Dust Storm Damage, 1930-1940. Accessed February 4, 2014.

Freedman, A. (2013, September 14). Colorado's "biblical" flood in line with climate trends. Climate Central. Accessed February 4, 2014.

McKee, T.B., Doesken, N.J., Kleist, J., Shrier, C.J., Stanton, W.P. (2000, February) A History of Drought in Colorado. Accessed February 4, 2014.

NOAA. (2013, January). NOAA Technical Report NESDIS 142-5. Accessed February 4, 2014.

Raabe, S. (2013, June 6). Southeastern Colorado wheat crop a disaster from drought, freezes. The Denver Post. Accessed February 4, 2014.

Ray, A.J., Barsugli, J.J., Averyt, K.B. (2008).Climate Change in Colorado: A Synthesis to Support Water Resources Management and Adaptation. University of Colorado at Boulder. Accessed February 4, 2014.

Seager, R., Herweijer, C.,Cook, E. (2011). The characteristics and likely causes of the Medieval megadroughts in North America. Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University. Accessed February 4, 2014.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln. (2013, November 12). U.S. Drought Monitor. Accessed February 4, 2014.