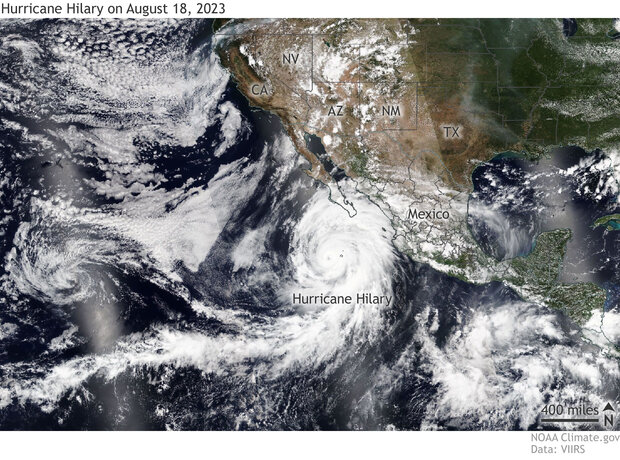

Hurricane Hilary made waves last week as it churned off the west coast of Mexico and tracked north toward Southern California. The tropical cyclone rapidly intensified, which is an increase in maximum sustained winds at least 30 knots (35 mph) in a 24-hour period, peaking at major, Category 4 hurricane status on Friday. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) issued its first ever tropical storm watch for parts of southern California (later changed to a warning) as the system approached the coast.

Hurricane Hilary in the eastern North Pacific south of California on August 18, 2023. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on NOAA-20/VIIRS data.

While Hilary did not make landfall in southern California, it did make landfall over the northern Baja California Peninsula in Mexico as a tropical storm on Sunday according to the NHC, and maintained tropical storm status as it crossed into Southern California on Sunday.

Hilary has made a very short list of storms that have maintained at least tropical storm status while tracking across parts of Southern California, the last of which was Hurricane Nora in 1997, according to NOAA historical hurricane track data.

[Editor's note (update February 20, 2024): A final analysis concludes Hilary was not a tropical storm over California. From the National Hurricane Center (pdf):

Operationally, Hilary was shown to have moved into southern California as a tropical storm. For each tropical cyclone, the NHC performs a routine post-analysis to analyze all available data (some of which were not available in real time) and determine if changes to a storm’s location, intensity, or status are necessary. As Hilary approached land, significant interaction with an upper-level trough disrupted the convective organization of Hilary and caused the cyclone to lose tropical characteristics shortly after landfall. Thus, it is determined in post-analysis that Hilary degenerated to a post-tropical low over northern Baja California.]

It is quite rare for a tropical storm or hurricane to maintain its strength and tropical characteristics in this part of the world, due to cool ocean waters and currents as well as prevailing trade winds that blow from east to west in this area.

Cool ocean waters

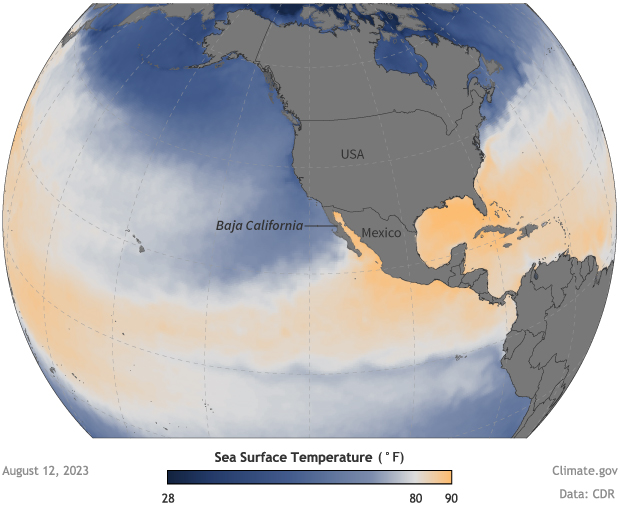

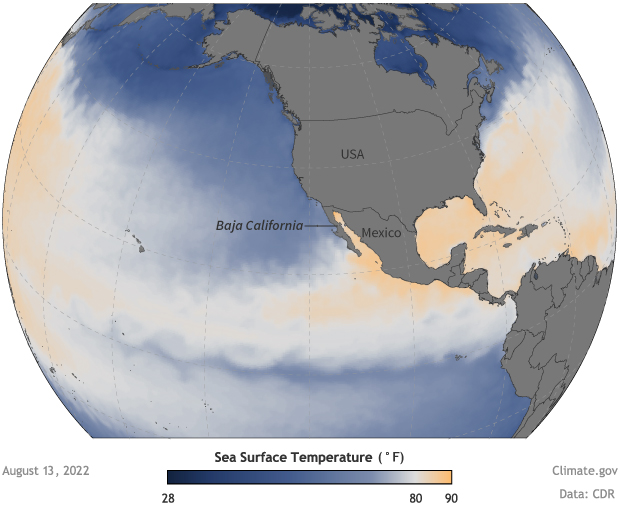

Tropical cyclones need warm ocean waters, of at least 79 degrees Fahrenheit (26 degrees Celsius), to develop and/or maintain their strength. Waters off the U.S. West Coast generally do not reach this threshold in large part due to the California Current which brings cold waters from Alaska south along the West Coast and northern Baja California.

Sea surface temperatures are typically in the 50s and 60s off the central and southern Pacific Coast, according to data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information. However, in late summer and into September, the waters may sneak into low 70-degree territory, which is the most common time to see remnants of tropical systems impact this region.

Waters in the eastern North Pacific near California are generally too cool to support hurricane formation. This comparison shows how even though there was a larger pool of hurricane-friendly water (yellow and orange colors) south of Baja California in mid-August 2023 than this time last year, waters off Southern California were still too cool (blue) to allow Hilary to maintain strength. NOAA Climate.gov images, based on Climate Data Record data from NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information.

Despite current sea surface temperatures being slightly warmer than normal just off the Baja California Coast and portions of the Southern California Coast, according to NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, sea surface temperatures were only registering between 65 and 72 degrees over the weekend. This is one reason Hilary was weakening as it approached Mexico and the United States.

Prevailing winds

Another reason it is very rare to see tropical cyclones impact the US West Coast is that the region’s prevailing winds—the northeast trade winds—blow generally westward, away from the coasts of the United States and Mexico. These winds tend to steer any tropical systems toward the open Pacific Ocean. They also aid upwelling ocean currents along the coast. The winds push water from the ocean’s surface westward, which allows deeper and cooler ocean waters to rise to the surface.

With Hilary, the normal easterly winds were shifted farther away from the coastline. Instead there was a strong ridge of high pressure over the south-central United States and mid- to upper-level low-pressure system off the West Coast, which allowed the storm to be pulled much farther north in the flow between the two systems, as was noted by a NHC discussion on Friday.

Despite weakening, Hilary brought flooding rains and gusty winds to Baja California and Southern California an area that is not used to seeing tropical rainfall, especially in their dry season, which typically runs from May to September.

So even though direct hurricane or tropical storm landfalls to the West Coast are quite rare, even indirect impacts from tropical cyclones can have a major impact, especially when it comes to rainfall. For rainfall and other forecast information for your area, visit Weather.gov.