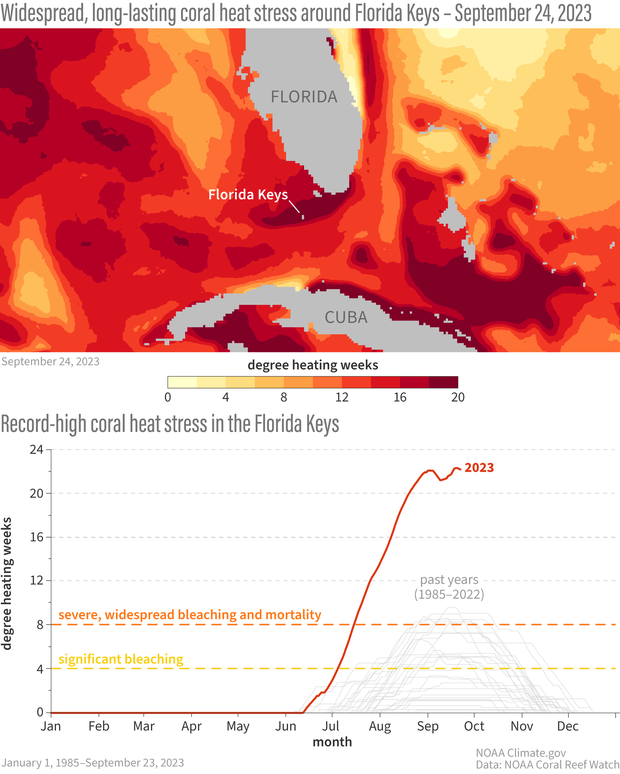

This summer, portions of the Florida Keys experienced an extreme marine heat wave. The cumulative heat stress to area corals was nearly triple the previous record. (See data for individual locations throughout the Keys.) In response to this heat wave, the coral reefs located in the Keys experienced an unprecedented amount of bleaching—expelling their partner algae and risking starvation. During dives on July 31 and August 1, NOAA scientists found the Cheeca Rocks reef in the Keys completely bleached. The widespread extent of the bleaching at this location shocked scientists, who have spent over a decade studying the corals there.

A record-high 22 Degree Heating Weeks (DHW) occurred this summer, nearly tripling the previous record of 8.5 DHW for the same region. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on data from Coral Reef Watch.

Marine heat waves and global warming

The ocean is storing an estimated 91 percent of the excess heat energy trapped in the Earth’s climate system by human-produced greenhouse gases. Recent studies (in Nature and Science) indicate that marine heat waves over the past century are becoming longer and more frequent, and these trends are expected to continue as the oceans continue to warm due to human-induced climate change. Experts have also implicated global warming as a major influence in specific events, including a 2021 Northwest Pacific marine heat wave that coincided with the Summer Olympics in Japan and a 2015/16 marine heat wave in the Tasman Sea. They have even concluded that some individual marine heat waves would not have been possible in a pre-industrial climate.

Coral reefs worldwide are facing a serious threat to their existence due to these extreme heat events and ocean acidification (the drop in ocean water pH as it absorbs atmospheric carbon dioxide). It is becoming increasingly important for scientists to track, monitor, and respond to how the ocean’s climate is changing as this can have great consequences for the life, ecosystems and biodiversity of these regions.

We spoke with Ian Enochs about some of these efforts. Enochs is the lead of the Coral Program at the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory’s (AOML) and principal investigator for climate monitoring in the western Atlantic and Caribbean as part of the NOAA’s National Coral Reef Monitoring Program (NCRMP), a coordinated cross-ocean effort for monitoring coral reefs in U.S. jurisdictions.

In late July and early August, Enochs (pictured here) and his team dove at Cheeca Rocks and found it severely bleached. NOAA photo.

“We monitor temperature and carbon dioxide levels to characterize the acidification of coral reefs. We also measure coral cover and their ability to produce habitat, which are linked both to warming as well as acidification,” Enochs said. “The reason we focus on these things, in particular the habitat formation and production, is because that reef framework is ultimately what is responsible for all of the ecosystem services that we rely on. The storm surge protection, the diving, fisheries, all of the remarkable biodiversity depends on that habitat. Without it, those services disappear.”

He went on to explain as ocean acidification progresses, it increases the rate at which the habitat erodes, also known as bioerosion, which slows down the growth of coral eventually leading to a net loss in that habitat.

“This is why we are so laser focused on these processes and the progression of climate.”

Adaptation and resilience strategies

There are several different adaptation and resilience strategies that NOAA scientists are engaged in and studying while this year’s coral bleaching event persists.

1. Data Coordination

“One the things we are involved with is data coordination. We have created tools for sharing data across different existing coral nurseries with different state, government, academic, and nonprofit partners as they grow different coral individuals for restoration,” Enochs said. “We compile this data and compare it across different genotypes and individuals so we have a good understanding of what the performance of a specific genotype or individual is.”

He compared it to planting a garden, saying if you have a full-sun garden you would not want to plant a shade-loving species there, as they would not be capable of thriving under sunny conditions. It is similar with corals: his team compiles and compares data to see what conditions certain corals will thrive under.

2. Strengthening resilience

Enochs and his team are also conducting different experiments to test and perhaps strengthen the resilience of corals within their labs.

“We are also involved with the evaluation of stress-hardening techniques. One of the multiple ways we have been investigating is looking at how environmental variability, specifically intermittent exposure to [heat] stress, can lead to greater thermal tolerance,” Enochs said. “We are focused on using natural mechanisms of resilience. For instance, in the wild, corals that have been in tidal pools that get really hot during the day and cool down at night, can be more thermal tolerant. We want to know if we can effectively operationalize that and make it a tool for making corals more tolerant to stress.”

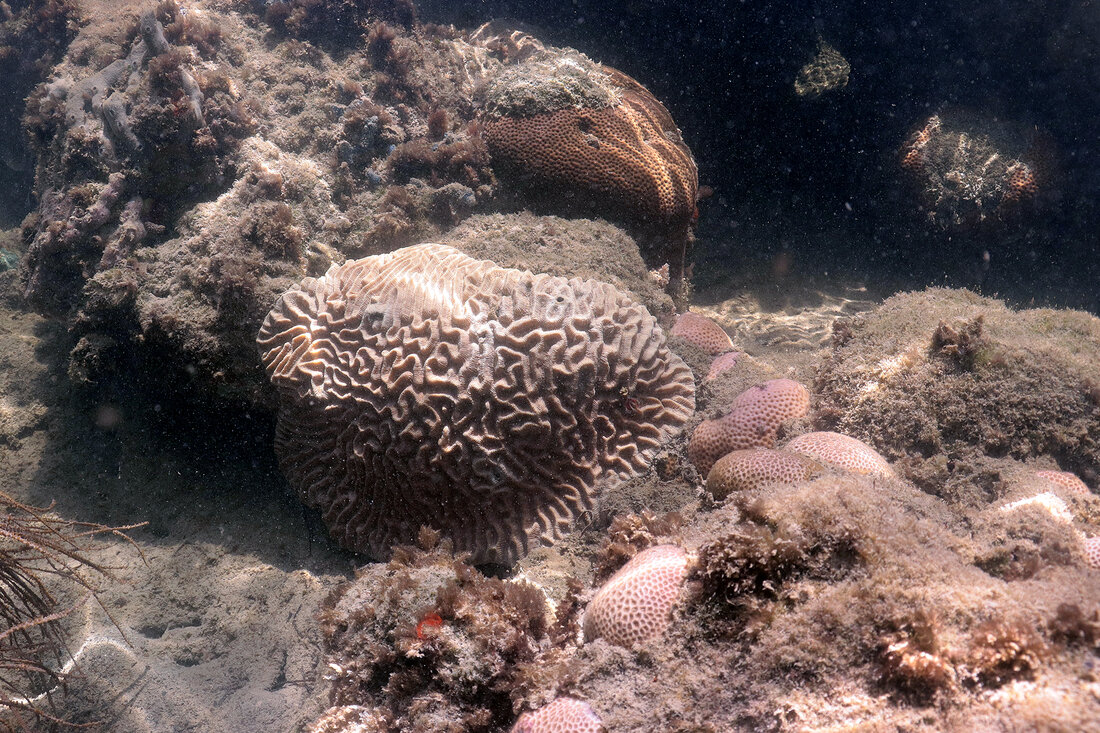

A paling colony of brain coral (middle) with multiple bleached colonies of starlet coral in the foreground – instead of becoming a pale white like many other species when bleached, this species produces a fluorescent sunscreen-like compound that appears bright pink or purple. NOAA and University of Miami photo.

Twice a day they shocked the corals in the lab by subjecting them to higher temperatures, followed by more tolerable conditions and found that after some time the corals were able to better withstand longer-term temperature stress. He cautions that although this tool has shown some degree of success, it is not a silver bullet and needs to be integrated into a larger restoration approach.

The researchers are also looking into how nutrition may be used to fatten corals up before a heat stress event in order to make them more capable of dealing with stressful events better. So far, this technique is one that needs additional evaluation in a lab setting before being utilized on a wild reef.

3. Automation and expansion

Enochs explained his team and many other scientists across the world’s reefs are also working on automation and robotics in terms of how they can be more efficient in the coral restoration process.

“The scale of the problem that we are dealing with is one that is not simply going to be addressed by people growing things on a small scale, so we are interested in techniques to scale up production [of resilient corals for transplanting].”

4. Relocation and shading

In a NOAA media call in August, Andy Bruckner, a research coordinator with NOAA’s Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, outlined additional practices that were being done this year. One of which was relocating coral nurseries from shallow waters to deeper and cooler waters offshore.

They were also conducting some pilot interventions, like small scale shading experiments on land based coral production facilities as well as in the Great Barrier Reef among other locations. Bruckner explained that the shading is meant to reduce light, not temperature. “What we have seen is when these corals are exposed to really high temperature stress, if there is a compounding impact from high light level, that tends to make bleaching much more severe.”

These techniques represent just a fraction of some of the ongoing efforts to try to study and save these coral reefs in a time of record heat and unprecedented bleaching.

A little help from nature

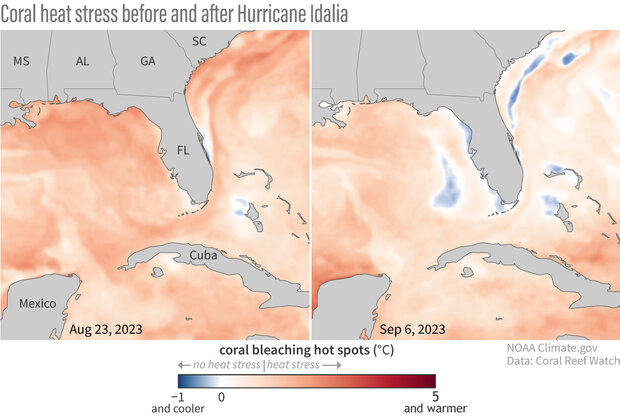

One event in recent weeks that has helped out the Florida Keys coral reefs was Hurricane Idalia. Idalia tracked across the Gulf of Mexico, just west of the Keys while rapidly intensifying. The hurricane utilized the extremely warm sea surface temperatures in the area to gather strength but in doing so left behind a wake of much cooler water.

“Hurricane Idalia caused strong cooling of the entirety of Florida’s Coral Reef and pushed temperatures below the bleaching threshold for the first time since late June/early July,” Derek Manzello, coordinator of NOAAs Coral Reef Watch Program said. “The storm effectively cooled sea surface temperatures around the Florida Keys by 1.7 degrees Fahrenheit (0.92 Celsius).”

(left) In late August, before Hurricane Idalia, much of the water surrounding Florida and the Keys was experiencing departures from average temperature high enough to cause heat stress. (right) In early September, after Hurricane Idalia, many cooled below heat stress values. These images are based on the NOAA Coral Reef Watch daily global 5km Coral Bleaching HotSpot product. Values of 1 °C or more indicate heat stress capable of causing coral bleaching, while values less than 1 °C indicate no heat stress. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on Coral Reef Watch data.

Enochs’ team returned to Cheeca Rocks in mid-September and while they did observe some dead coral colonies, they also saw color returning to some of the colonies that had bleached earlier this summer.

“This is wonderful news and is definitely associated with the cooler water conditions we have been experiencing. It does not, however, mean that we are out of the woods,” Enochs warned. He explained that during past bleaching events a lot of mortality occurred after the fact, with weakened corals being consumed by disease. Additionally, he noted that bleaching and thermal stress can lead to other issues with growth and reproduction down the line, even if the corals do not die.

Unfortunately, this cooling was short-lived and by mid-September sea surface temperature anomalies already rebounded to 2 to 4 degrees Celsius above normal. This has prompted a Level 2 Bleaching Alert to return to the Keys, meaning that severe bleaching and significant mortality continues to be likely, according to NOAAs Coral Reef Watch.

Hope remains

This year has been an incredibly tough year for many coral reefs globally, but especially those near Florida and in the Caribbean. For Enochs and other scientists, this cause is deeply personal.

“I have never seen people so motivated to do positive good to restore these reefs and make sure that we are not losing the last reefs that we have. In the face of all this doom and gloom, we still need to hold on to some hope,” Enochs said. “We all can, we all have to work together to lower our carbon footprint. The problem is big enough that it will not be solved by a single individual, rather we ALL need to tackle this together at scale.”