Slow slosh of warm water across Pacific hints El Niño is brewing

Details

The El Niño / La Niña climate pattern that alternately warms and cools the eastern tropical Pacific is the 800-pound gorilla of Earth’s climate system. On a global scale, no other single phenomenon has a greater influence on whether a year will be warmer, cooler, wetter, or drier than average. Naturally, then, the ears of seasonal forecasters and natural resource managers around the world perked up back in early March when NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center issued an “El Niño Watch.”

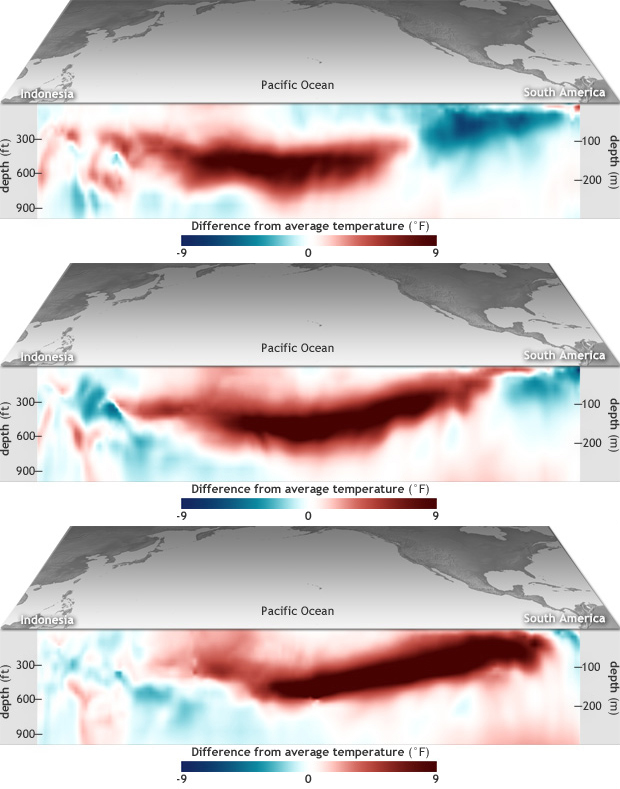

The “watch” means that oceanic and atmospheric conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean are favorable for the development of El Niño within the next six months. These maps reveal one of the most significant of those favorable signs: a deep pool of warm water sliding eastward along the equator since late January.

The maps show a cross-sectional view of five-day-average temperature in the top 300 meters* of the Pacific Ocean in mid-February, mid-March, and mid-April 2014 compared to the long-term average (1981-2010). (Mouse over tabs below the image to see different dates.) Warmer than average waters are red; cooler than average waters are blue. Each map represents a 5-day average centered on the date shown.

The pool of warm water was lurking in the western Pacific in mid-February, but it shifted progressively eastward in the subsequent two months. By mid-April, the unusually warm water was close to breaching the surface in the eastern Pacific off South America. NOAA declares El Niño underway when the monthly average temperature in the eastern Pacific is 0.5° Celsius or more above average.

Such warm surface waters are unusual in the eastern Pacific because the prevailing wind direction across the tropics is east to west: from South America to Indonesia. The easterly winds pile up sun-warmed surface waters in the western Pacific like gusty winds build snow into drifts. Average sea level is literally higher in the western Pacific than the eastern Pacific.

As the warm surface water is pushed westward by the prevailing winds, cool water from deeper in the ocean rises to the surface near South America. This temperature gradient—warm waters around Indonesia and cooler waters off South America—lasts only as long as the easterly winds are blowing.

If those winds go slack or reverse direction in the western Pacific, the warm pool of water around Indonesia is released and begins a slow slosh back toward South America. The slosh is called a Kelvin wave. If the Kelvin wave has a strong impact on the surface waters in the central and eastern Pacific, then it can help change the atmospheric circulation and trigger a cascade of climatic side effects that reverberate across the globe.

Will the odds of an El Niño event increase or decrease as summer arrives? How can one climate pattern have such a powerful effect on weather far away? For answers to these and other questions, keep an eye out for a new blog planned for launch on Climate.gov in coming weeks. Produced by scientists from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, the blog will follow the developing El Niño from the perspective of scientists at the United States’ operational climate prediction center.

*The surface map part of this image and the ocean depth part are not to relative scale. The Pacific Ocean is thousands of kilometers across at the equator. If we showed the sub-surface temperature anomaly data at that scale, 300 meters of depth would not even occupy a single row of pixels in the image!