What's it like to be an author for the IPCC report?

Today, Working Group I of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) presented 14 chapters, a Technical Summary, and a Summary for Policymakers to IPCC member governments for approval and acceptance. This report represents the first of four sections that will make up the IPCC's 5th Assessment Report. The Summary for Policymakers is available here, and the full Working Group 1 report, “Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis,” is available here.

For this latest report, more than 250 scientists from around the world evaluated all the peer-reviewed studies about climate change that were published or accepted for publication before April 2013. They presented new evidence to support a series of scientific conclusions: that climate change is real and caused by human activity, and that the need to address it is more urgent than ever.

Ron Stouffer and Gabriel Vecchi of NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) in Princeton, N.J., share their experiences working on one of the most comprehensive scientific documents in history.

Ron Stouffer and Gabriel Vecchi of NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory.

Gabe, this was your first time being a lead author for the IPCC report. How is this different from your day-to-day job at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory?

Gabe: It’s a whole host of commitments, being a lead author. My son was one year old when I left on my first IPCC trip. I didn’t want to be gone from my family for a week at that stage. And now he’s four years old and getting his first big boy bike. So it’s a really long-term commitment: four years of your professional life.

[Another difference is] the assessment report is not our own research. It’s our synthesis of the research that is in the published literature, some of which may be your own personal research and interpretations of the data. A fraction of your own work might make it into the report, or it might not. So you have to read a lot of papers—many more than you end up actually citing, because you’re trying to find some coherent structure within them or inconsistencies. And then, there’s the international aspect. There is a lot of travel, and there are a lot of phone meetings at weird hours because you want to involve people across all continents...

Ron: You haven’t mentioned the 50 million emails.

Gabe: Oh, and the emails! Emails and emails. What’s interesting is that as these emails come in, you can see the work day move around the planet. Because you’ll wake up in the morning and check your email and see the first email comes from your colleague in Hawaii, then your colleague in New Zealand, and then your colleague in Japan — all the way around. By the time a document has been handed off to you, it’s already been edited many times and you better do it in a hurry before your colleague in Chicago gets it.

So it's a big commitment, but it also seems like a big honor. How did you both come to be a lead author?

Ron: I was at one of the first lead author meetings for Working Group I held anywhere on the planet. It was at GFDL in the late 1980s. I sat in on that meeting and I got interested in it. One of the following lead author meetings was in Brisbane, Australia, and my boss was a convening lead author. He didn’t want to fly all the way to Brisbane so instead, he sent me! That’s how I got involved in the process.

For the next three reports, I was involved in the process the whole time, serving as an author. I was also was involved in writing the Summary for Policymakers [for Working Group I] and the Summary for Policymakers for the Synthesis Report. For this latest report, I served as a reviewer.

Gabe: I first heard about [the IPCC] when I was in college in the ‘90s. In the news, they were talking about a climate change report that came out but I didn’t really know what it meant. I don’t think I ever thought I’d be a part of it. At the time, I was more focused on things like El Niño and variability in my research. Climate change wasn’t on my scientific radar. Then I came to GFDL and was surrounded by a lot of different people who did climate change research. Little by little, I started shifting my research interests to include more and more the climate change problem.

At the laboratory, an email went around asking us if any of us were interested in being lead authors, contributing authors, or review editors, and for which chapters we were willing to do it. So I submitted my name and listed the chapters that I would want to do. From that point, a collection of nominations must have gone up the chain. The United States State Department sent a set of names out to be evaluated by the United Nations so that they could see if they had the right combination of experts and so forth.

At some point, in early 2010, I got an email that I had been selected and asked if I would still be willing to be a lead author on Chapter 11 [of the 5th Assessment Report]. This chapter wasn’t in the previous reports. It focuses on how variability and change come together to give you the climate that you’re likely to see over the next few decades. It was a broadening of my horizons and a broadening of the IPCC’s horizons. It was a neat opportunity.

So at first, there’s this feeling: “Wow, they selected me, how nice.“ And then: ”Wait a second, now I have to decide. Am I really willing to do this or not?” It actually took a while to decide because it’s not just a commitment of my time, it’s a commitment from my family. We eventually decided that yes, it was going to be a lot of work, but it was worth it and an important contribution. So I accepted.

Are you glad you did it?

Gabe: Ha! Ask me in a few weeks…. Personally, by the time the review round came around, I was so burnt out I had a hard time providing feedback for other chapters. It was tough. Going into it, you think you know what you’re getting into but you don’t really know until you’ve done it. I think now I can reflect a little because my role in it is pretty much done.

But in addition to the sense of participating in what is a very important enterprise, I think there have been some interesting questions that I’ve thought about for future work. There are some interesting relationships I’ve developed throughout this process that are good for me, some potential collaborations.

Ron, for this latest report, you helped design and evaluate the IPCC modeling experiments that took place in advance of the forthcoming report. Why must modeling experiments be designed specifically for the IPCC process?

Ron: The way you phrased it is a very common misconception. Actually, the CMIP [Coupled Model Intercomparison Project] panel—a subcommittee of the World Climate Research Programme—designs experiments to get at the science, to understand: why do models behave like they do? The lead authors of the IPCC can use that data, but so can other scientists who write papers on what they find. Those papers end up being a part of the assessment process that Gabe went through this time. But CMIP doesn’t design experiments for the IPCC per se; it designs them for the science.

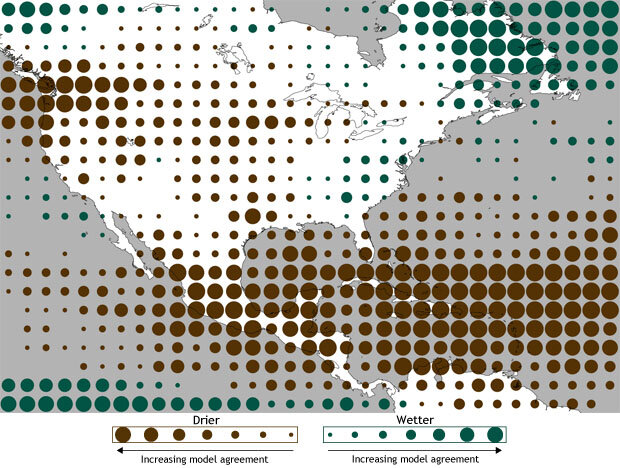

Do models agree on how global warming will change precipitation across North America? In one CMIP experiment, fourteen global climate models projected how summer (June-August) precipitation would change by 2070-2099 compared to modeled precipitation from 1961-1990. Our featured image has more detail. Map by NOAA Climate.gov, based on data from Baird Langenbrunner and David Neelin, Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of California - Los Angeles.

Gabe: So, for example, rather than have this report scattered about with, for example, one figure that is an anomaly relevant to 1971-2000, and another that is an anomaly relevant to pre-industrial climate, you have to come up with some consistent way of showing the results. The CMIP models become a tool by which you can do that. But then, you shouldn’t be making figures that present some sort of new result or level of understanding that is not contained in previously published papers.

Most scientific papers in journals are the collaboration between a small group of scientists, and are peer-reviewed by two or three experts. The IPCC report, on the other hand, is based on the work of more than 250 scientists and experts from nearly 40 countries who receive more than 50,000 review comments. How do the report’s authors work together to ultimately reach the scientific conclusions that make it into the final report?

Gabe: Before the IPCC lead authors are even contacted and decided upon, there’s a scoping meeting that occurs that identifies what the layout of the IPCC report will be, what the chapters will be and what the scope of each chapter will be.

Then comes the process of combing the literature. Papers start trickling in. You and your co-authors share them with each other, you start collecting them, you put them in piles, and your office ends up looking like a horror show. In this whole process, you’re writing what will be become the zero order draft. It’s called zero order because it’s really rough, it hasn’t had much feedback. So you write that, and you send that in for review. The review is usually incredibly harsh, and rightly so.

Ron: It’s called a ”friendly” review because it’s only a select handful of scientists that are invited to comment on specific chapters in this review round. It’s not like the other reviews where anyone can ask to be a reviewer. I think Gabe had the misfortune of having me as one of his reviewers this last time. I had the easy job!

Gabe: Yeah, Ron had the easy time. His job was to read the report and just start hurling things over the fence at me saying, “Fix it.” And then I had to fix it. With every draft’s review process, you argue, you debate with your co-authors, and you try to figure out how you’re going to respond to the comments. Each draft has more references, a cleaner structure, cleaner results, cleaner assessments.

Ron: The first draft goes out for expert review — only people who can claim some level of expertise on the manner. That’s a big group of people. Climate science is a very integrative science. There are statisticians, civil engineers, amateur scientists, physicists — they can all claim expertise, and rightly so. The second draft goes out to experts as well as reviewers selected by all the countries involved, and the third extends the circle to non-governmental organizations.

Gabe: Meanwhile, you’ve got to make sure that your chapter is consistent with the other chapters. You argue with other chapter authors over who is going to say what. Each chapter has a certain number of words and certain things need to be included. We’re fighting under a tight space constraint. Well, I shouldn’t say fight…

Ron: It’s a negotiated settlement!

Gabe: Right! And then the fourth draft, or last draft, is what comes out [this week], along with the Summary for Policymakers. Whatever ends up in the Summary for Policymakers must match what’s in the assessment chapters. And each bit of text in those chapters is supported by published literature. So you can see, these statements are incredibly buttressed. Literally every line has been reviewed.

Wow, it sounds like there is a lot of debate throughout this process. How do disputes get resolved?

Gabe: I think where there are truly scientific disagreements, in my experience, we highlight it in the report. If we can’t come to consensus, we don’t come to consensus. We explain that this particular topic remains a challenge and explain why it is a challenge. And then somebody researching this down the line will hopefully come and take a look at that, and find a way to reconcile the disagreement, maybe by proving somebody wrong.

Ron: For example, during the process when the Summary for Policymakers is approved, if the representatives can’t agree on specific words or phrasing or points, what will happen is they will actually make footnotes and they’ll say “Countries A, B, and C do not agree to this statement.” That has not happened on Working Group I reports but it’s happened on Working Group II and III reports.

You know, I’ve always said that scientists are trained to not talk about what they agree on but focus on their disagreements. But the IPCC is a process that is about 180 degrees off of that. The idea is to find consensus among a group of authors and then to clearly define the places of disagreement. Scientists love to spend all their time arguing about the disagreements rather than the agreements. But in the IPCC writing, most of the writing should be about the agreement part, the consensus part. It’s a different kind of process for most scientists and one that we’re not well trained for. You have to learn how to do it.

Gabe: What we do, our main topics of research, and our own main interpretations of the data and the theory, are generally foremost in our mind. But this is a process that is much more explicit about considering the other — looking at the big picture and the broad evidence. This is one aspect that is very unique about this report: the extent to which it considers many different points of view. It makes you have to take a much humbler view of your own work. It’s very, very different. What comes out of the process is a much more robust assessment of our state of understanding and the way the world works.

Is there anyone that is just flat-out skeptical of the science?

Ron: Skeptic is one of those interesting words because scientists are supposed to be skeptical by nature. So having that as a moniker for a set of people who don’t believe in global warming, I don’t like that very much.

Gabe: I would hope that the reviewers were all to some degree skeptical of what was written [in the initial drafts]. They wouldn’t be very helpful reviewers if not. Everyone with expertise on the matter was included by the review structure of the process.

Have some of the conclusions remained the same from the last report, or even from the very first one? What can we expect to learn from the latest report?

Ron: The pattern of warming hasn’t changed much. The statements about certainty are becoming more certain over time about the human influence on climate. Climate change by 2100 — that story is not going to change much from past reports. The new thing on this report is actually taking a hard look at near-term climate change over the next several decades.

Gabe: For global mean temperature a hundred years from now, I think it very much becomes a story of CO2. Things in the middle part of the next century, from now until somewhat closer than mid-21st century, become a very subtle and interesting question, especially as you look regionally. CO2 is an important player in timescales of decades, but it’s not the only player. There are other elements at play, such as other trace gases, changes in aerosols — not what comes out of the spray can but little particles of soot and dust in the air. There are also modes of natural variation in climate such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, or the variations that arise when the North Atlantic circulation speeds up and slows down.

The chapter for which I served as a lead author for the latest IPCC report focuses on how variability and change come together to give you the climate that you’re likely to see over the next few decades. As we look at the last 10-15 years and as we’re looking forward, we need to look at how the rate at which we force climate change — be it from [increased levels of] carbon dioxide or aerosols — and natural climate instability are intertwined. Understanding what will happen at any given place or at any given period of time that is shorter than the next 100 years really involves considering these aspects of climate science together.

We’ve heard about some of the challenges inherent in being an IPCC contributor: time away from family, extra hours spent working, the vast amount of feedback you need to address during the writing process. But what are some of the rewards?

Gabe: Well, a lot of them are intangible. There’s the sense that you’ve contributed to an important project. So I can look back and say, I did my part as a scientist. As scientists, it’s our responsibility to make sure this report is written in as correct a manner as possible. I mean, really, it’s very much community service.

Ron: For one of the previous reports, I went through the process of finalizing the Summary for Policymakers. The Summary for Policymakers is approved by representatives from all the countries, and it’s a process that typically takes about 3 days. It goes day and night. It’s incredibly intense. I’ve been involved in these things where I was awake for 36 straight hours in conferences and meetings, talking about the wording. They literally go through it line by line.

The people who set up the IPCC originally were trying to divorce the arguments over the science from the political arguments of what to do about the science. During the Summary for Policymakers approval process, you see those two forces intersect and you can see it happening right in front of you as a participant in that process. You know, there were folks that had agendas that were obvious and there were folks who were just trying to communicate the science better, trying to get the wording right. That was a very eye-opening experience for me. It was a fascinating process and it gave me a much larger sense of community service than I had before I went through that.