After a slow start to the eastern Pacific hurricane season, ten named storms have formed since July 2, turning a below-average start into an above-average hurricane season in the blink of an eye.

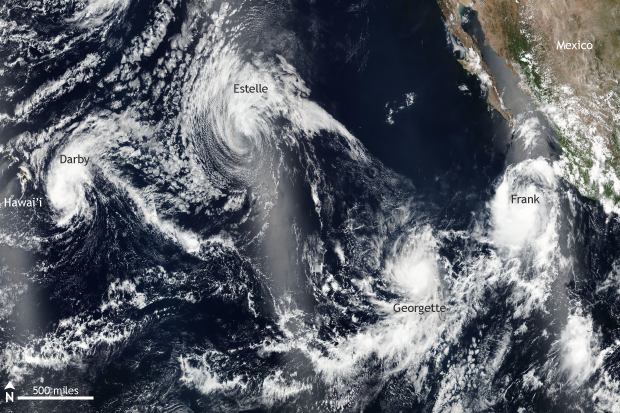

Eastern North Pacific Ocean on July 22, 2016. At the time, four tropical storms were spinning, with one (tropical storm Darby) about to make landfall in Hawaii. NASA/NOAA Suomi-NPP VIIRS satellite image from NASA Worldview.

The first named storm of the 2016 eastern Pacific Ocean hurricane season, Agatha, did not form until July 2—more than three weeks later than normal. In fact, it was the slowest start to the hurricane season in this part of the globe during the satellite era (1971-present). Fast forward to August 7, and the tenth named storm tropical storm, Javier, spun into existence more than three weeks earlier than normal (September 1st).

The breakneck speed at which ten named storms formed set a record for the eastern Pacific Ocean. And the month of July tied a July record for most named storms (seven) forming and set a new July record for most hurricanes at five.

All this activity makes for some stunning satellite shots. A conveyor belt of four tropical storms churned away on July 22, when the satellite image above was captured. The most dangerous was Darby (far left), which at the time the satellite passed overheard on July 22 was a tropical storm close to making landfall on the island of Hawai’i. Darby would become the first storm since Iselle in 2014 to impact the islands directly and the fifth storm ever to make landfall in Hawaii since records began in 1949. Darby dropped over half a foot of rain on the Big Island, up to 8 inches in Maui, and 7 inches on Oahu. Flash flooding across the islands inundated roads and bridges, but luckily there were no fatalities.

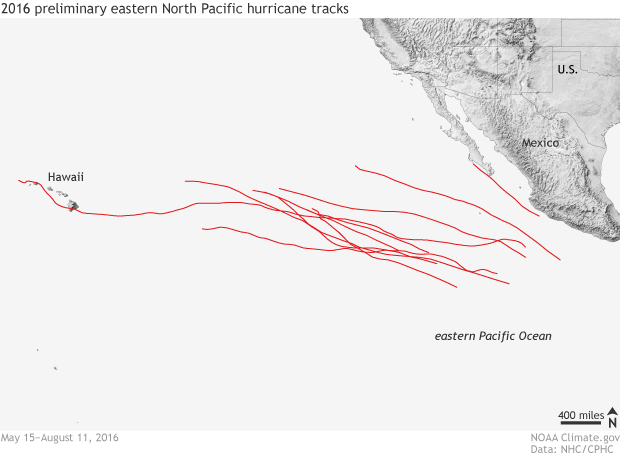

Eastern North Pacific hurricane season preliminary storm tracks, valid from May 15–August 11, 2016. A slow start to the season was erased during an incredibly active July and beginning of August. Climate.gov image based on data from the National Hurricane Center and the Central Pacific Hurricane Center.

The cradle of creation in the eastern Pacific

The waters in the tropical eastern Pacific have been slightly above-average dating back several months, likely related in some way to the near record 2015-2016 El Niño. However, during the beginning of the hurricane season, which started May 15, the atmosphere was simply not conducive for storms to take advantage of the warm waters below. That atmospheric switch was flipped in July with less wind shear—change of wind direction and speed with height—and increased amounts of rising air. The flood gates opened.

Where the ten named storms formed and tracked shows a familiar pattern for not only this year but for hurricane formation in the eastern Pacific Ocean in general. Tropical systems tend to form in a tight region in the eastern Pacific Ocean where sea surface temperatures are warm and low pressure systems move to the west along the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ): the north/south migration line marking where the northeast trade winds in the northern hemisphere meet up with the southeast trade winds of the southern hemisphere.

This particular area is friendly to hurricane formation because if a low-pressure storm system organizes itself into a tropical system, it can strengthen rapidly over warm water while usually continuing to track to the west. However, unlike in the Atlantic Ocean, where westward-moving tropical storms and hurricanes continue to encounter warm water and an increased risk of landfall, when storms move north and west in the eastern Pacific Ocean, they begin to run into cooler water, and land is at a minimum.

The difference in the two basins is usually good news for Hawaii, as storms tend to weaken before making it that far west, although hurricanes have hit the islands in the past. Luckily, most storms that form in the eastern Pacific never impact land, but instead are “fish” storms, roiling up the water beneath them and the fish that swim underneath.