When will the Tanana River ice break up?

In 1917, a group of railroad engineers bet 800 dollars guessing the exact date and time that Alaska’s Tanana River ice would break. Almost 100 years later, the Nenana River Ice Classic competition continues, and participants closely observing the local climate might have an edge.

The official Nenana Ice Classic tripod. Photo taken on March 24, 2009, by Flickr user James Brooks, some rights reserved.

Located in the interior of Alaska on the bank of the Tanana River, just upriver from its confluence with the Nenana River, the town of Nenana is home to less than 400 people, according to the 2010 Census. The Tanana River usually begins to freeze in October or November. In early March, a tripod is planted 300 feet from shore in about two feet of river ice, as seen in the photo above. It is connected to an on-shore clock that stops when the ice gives out and the tripod tumbles into the water.

The history of the annual plunge of the Tanana River tripod provides a record of interior Alaska’s spring climate since the time of World War I. According to that record, kept by the National Snow and Ice Data Center, ice on the Tanana River generally can break up anywhere from April 20 to May 20. The ice went out last year at 3:48 p.m. on April 25, but the ice is currently thinner than it was at this time last year. As of April 6, the ice measured 33.5 Inches. On April 7 a year ago, the ice measured 36.8 inches.

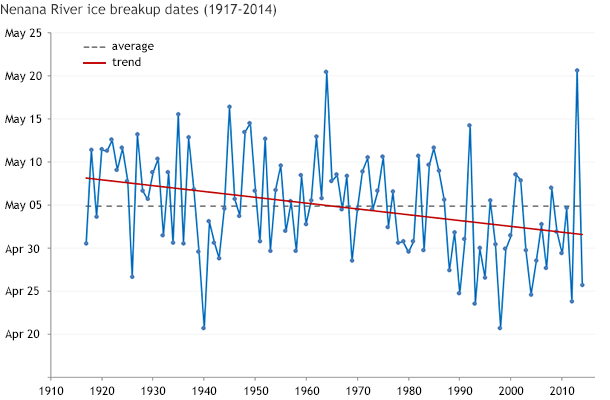

Tanana River ice break-up dates from 1917-2014. The historical average break-up date is May 5, indicated by the gray dotted line. The red trend line indicates that the break-up date is moving earlier over time. NOAA Climate.gov graph courtesy of data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

For a competition so closely tied to the climate, it makes sense to get a local expert’s analysis. Rick Thoman, Climate Sciences and Services Manager for the National Weather Service’s Alaska Region, says by far the most important factor for the timing of ice break-up are spring temperatures, especially the timing of warm or cold spells. Secondary factors include winter snowfall (which dictates water levels in the river), winter temperatures, and ice thickness.

“Break-up of the Tanana River at Nenana takes place in two basically two different ways,” Thoman says. “One, referred to in Alaska as a ‘mush-out,’ occurs when the ice gradually rots in place and the water flowing in the river gradually increases as snow upstream melts and runs off. This typically happens when daily temperatures are well above freezing during the day and then it freezes hard at night.

“The other way occurs when the volume of water flowing in the river rapidly increases, and the ice is lifted and mechanically broken up. This typically happens when there is a dramatic warm-up in mid- to late-April or early May, and is more likely with deeper snowpacks.”

This year, Alaska’s full cold season—from October (when the ice starts forming) through March—was the third warmest on record since the winter of 1925-26. But in the Southeast Interior where Nenana and most of the Tanana River drainage is located, it was a little cooler overall, ranking as the 11th warmest cold season on record. But it was warmer than that same period last year, which came in as the 15th warmest.

Although it may seem counter-intuitive, low snow winters generally produce thicker ice cover. Snow acts like an insulating blanket over ice, protecting it from changes in the air temperature aloft. If this insulating effect is reduced, the ice can grow thicker. “Typically, low-snow autumns can result in thick ice, Thoman says. “Even in a low-snow winter, there would typically be a foot or more of snow on the ice by New Year’s.”

Another way of looking at the Tanana River ice break up. Data data from 1917-2014 divided into three categories: later than average (green), near-average (gray), and earlier than average (pink). Notice how earlier-than-average break up dates (pink dots) dominate recent decades. The black trend line also shows that the break-up date is getting earlier. NOAA Climate.gov graph courtesy of data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Apart from providing a fun challenge each spring, Thoman says the Nenana Ice Classic provides a useful, “non-instrumental” record of long-term changes in spring temperatures and the earlier ice-break ups in Interior Alaska over the past century. “The ice break-up record at Nenana is unique in the consistency of how the data has been gathered,” Thoman explains. “There is no reason I’m aware of to ascribe the earlier break-ups to purely local changes.”

He cites the fact that Nenana has always had a population of 200-700 people, and remains mostly untouched by the urban impacts of Fairbanks about 60 miles upriver. The Tenana also runs in a single channel at this location, unlike other reaches of the river with multiple channels, where the amount of water running in any particular channel fluctuates greatly. He also points to ice break-up dates that have been collected for the Yukon River at Dawson City, Canada, since the late 1890s.

While their measurements have not been gathered using the consistent method used in Nenana, the data shows exactly the same pattern: little trend until the 1970s, and then a steady decrease. These trends in river ice break-up are one more indicator of the impacts of climate change in Alaska.

References

Official Website of the Nenana Ice Classic

National Snow and Ice Data Center. 1998. Nenana Ice Classic: Tanana River ice annual breakup dates. Boulder, CO: National Snow and Ice Data Center. Digital media.

National Centers for Environmental Information’s Climate At A Glance