After the second driest winter on record, state-wide California came into spring dry. It is leaving March much wetter, as a soaking atmospheric river brought copious amounts of rain during the third week of March.

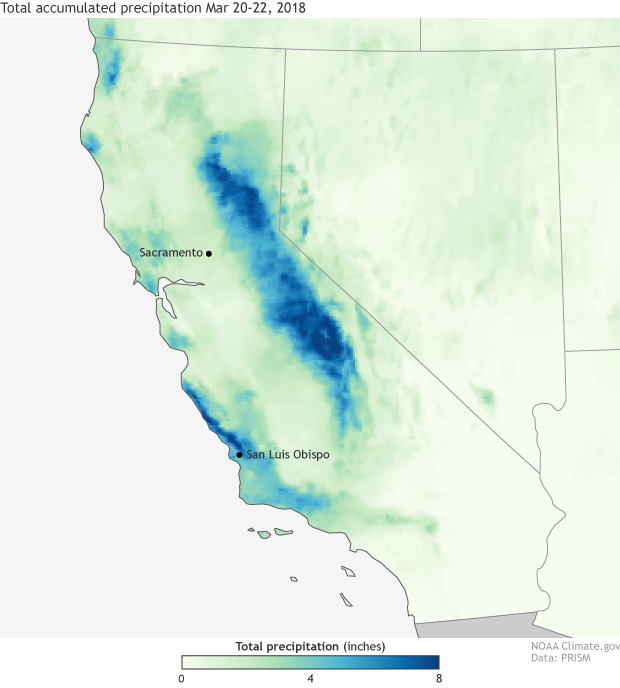

Total observed precipitation from the PRISM dataset for March 20-22, 2018. Precipitation amounts are determined through a combination of radar estimates and rainfall gauge reports. An atmospheric river event in late March brought heavy rain and snow to a wide portion of California. NOAA Climate.gov image using data from PRISM.

From March 20-22, an atmospheric fire-hose known as an atmospheric river led to a tremendous amount of rain and higher elevation snow across much of California. Three-day rainfall amounts exceeded 10 inches in Rocky Butte in San Luis Obispo County, the worst hit area. Meanwhile, areas near the burn scar from the Thomas fire—the largest fire in state history—recorded around five dangerous inches of rain, raising fears of mudslides. Leading up to the event, evacuations were ordered for the most landslide-prone locations. In general, 2-6 inches of rain fell during just three days for much of southern California.

In northern California across the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the snow was measured in feet, significantly boosting snowpack. Just this month in Squaw, nearly 230 inches of snow fell, accounting for about 60% of the season total to date.

In other good news, the reservoir at Folsom Lake in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains has risen more than 33 feet in a little over two weeks thanks to the rains. This water storage will be beneficial once the dry summer months arrive.

March overall was one for the record books. As of March 23, it already has been the tenth wettest March for the northern Sierra, and fourth wettest for the San Joaquin and Tulare regions, based on preliminary statistics. And it’s also been the wettest month of the 2017-2018 Water Year so far, an unusual fact as most rains fall in the winter months.

However, even with the rain and snow from this event, thanks to the dry winter months, many places still are running below average for the water year—October through September. Sacramento is only around 80% of normal as of the end of March, for instance.

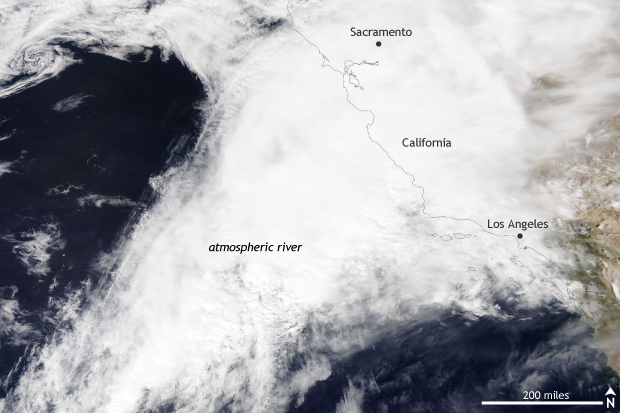

NASA AQUA MODIS satellite image taken of the West Coast of the United States on March 20, 2018. An atmospheric river event brought heavy rain and snow to California, greatly increasing water year precipitation totals after a dry winter. NOAA Climate.gov image using data provided by NASA Worldview.

Atmospheric Rivers did this? Remind me what those are again.

Atmospheric rivers are long, narrow bands of moisture in the atmosphere—250-375 miles wide—that act like an atmospheric version of a “people mover” at an airport. Instead of weary travelers dragging luggage, an atmospheric river is transporting a different type of baggage to the mid-latitudes: tropical moisture.

These atmospheric rivers—called “Pineapple Expresses” when they look like they are originating from Hawaii—are a blessing and a curse for the West Coast of the United States.

On one hand, 30-50% of the annual precipitation comes from just a few of these atmospheric river events per water year. And Californians rely on the water and snow these events bring to help the state get through the dry summer months.

However, the payoff for the dry summer months may look way too distant to appreciate when a lot of this precipitation falls over the course of just a few winter days. Torrential rains from atmospheric rivers also create a huge risk for mudslides and flooding.

Luckily, the worst fears of damaging mudslides did not materialize in this event but we only have to look back a couple of months to the mudslides in Montecito, California, at the beginning of January to see the results of torrential rains falling across denuded and burned mountainsides.