More often associated with famine and drought, the Greater Horn of Africa captured headlines for a difference extreme event in mid-May 2018: a landfalling tropical cyclone.

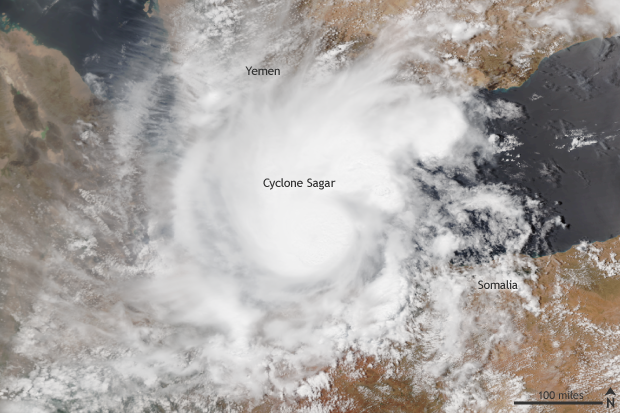

Suomi NPP satellite image taken of the Greater Horn of Africa and Gulf of Aden on May 18, 2018 using the VIIRS instrument. Cyclone Sagar became the westernmost landfalling tropical cyclone on record in the North Indian Ocean after it traveled through the Gulf of Aden and reached shore in northwestern Somalia. NOAA Climate.gov image using data provided by the NOAA Visualization Laboratory.

On May 19, Tropical Cyclone Sagar slammed into northern Somalia near the Djibouti border with winds of around 60 mph and heavy rain. If verified, the 60-mile-per-hourwinds would make Sagar the strongest landfalling tropical system on record for Somalia.

According to local news reports, 31 people died as a result of Sagar with thousands of people and livestock affected by flash flooding. The coastal villages of Yago and Garyaara have reportedly been damaged extensively.

This area of northern Somalia is also known as Somaliland, and, according to Reliefweb, has been mired in drought over the past five years. With the additional damage done by this storm, including the destruction of farmland and infrastructure and the loss of livestock, food security concerns will rise.

How rare was this?

Since quality records have been kept, this was the farthest west a tropical system has made landfall in the Gulf of Aden. Only two other systems even came close:

1) Cyclone Megh in November 2015 made landfall in western Yemen. At peak strength, Megh had winds over 100 knots, but it weakened considerably before landfall.

2) An unnamed storm in May of 1984 hit western Somalia as a weak tropical system.

In total, besides the unnamed storm in 1984, five other cyclones of varying strength have hit Somalia since satellite measurements came about in the mid-1960s. However, those five other storms all hit the east coast of Somalia. Not the north coast as Sagar did.

When do these storms tend to form and why are they generally so weak at landfall?

Well, first of all, they don’t tend to form much at all. But if they do, these cyclones tend to get their act together during the transitional seasons of spring and fall in the North Indian Ocean.

Outside of these transitional seasons, the India Ocean is dominated by the southwest flow of the summer monsoon and conversely the intense northeast flow that occurs in winter.

So while ocean temperatures are warm enough year round to sustain tropical cyclones, it is generally during the spring and fall when atmospheric conditions are conducive for the development of tropical cyclones in the North Indian Ocean.

Any storm that forms and begins to move west towards the Arabian Peninsula and the Greater Horn of Africa runs into another debilitating feature that serves almost as a force field for coastal communities in the region: a large amount of desert air.

As storms approach the coast, they begin to ingest this dry air, which usually weakens the storms rapidly before they make landfall. This doesn’t mean that no cyclone can make landfall, but it weakens any storms that do.

Currently, we will have another chance to see if this holds true as another cyclone in the North Indian Ocean, Cyclone Mekunu, is expected to hit Oman in the next several days. Certainly, it’s been an incredibly active couple of weeks for generally one of the least active tropical cyclone basins on Earth.