After five years of exceptional drought, desert landscapes across southern California exploded with “superblooms” of wildflowers this March following ample winter precipitation. According to local news reports, it’s the most spectacular display some locations have seen in more than two decades.

WIldflowers blooming in Anza Borrego Desert Park on March 12, 2017. Photo by Kyle Magnuson, via Creative Commons license.

Patient plants

Wrapped up snugly in a thick, waxy coat, the seeds of desert wildflowers may lie dormant on the seemingly barren ground for years. Washed and softened by unusually heavy or frequent fall and winter rains, the waiting seeds finally crack open and push their roots into the rocky soil. Provided that spring brings sunshine, warmth, and only gentle winds, the plants will take advantage of the narrow window of favorable conditions to complete their life cycle.

A desert lily blooming in Anza Borrego Desert Park on March 4, 2014. Original photo by Flickr user Rob Bertholf. A color correction has been applied to the original. Used under the terms of a CC license.

At least some desert wildflowers bloom in most years, but in “superbloom” years, they put on a spectacular show—a carpet of greenery and thousands of blooms stretching across acres and acres of the landscape. Like “leaf peepers” are drawn to New England in the autumn, visitors flock to desert parks to witness the phenomenon. Among the locations where seasonal climate conditions in winter 2016-17 were favorable for a spring superbloom is Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, in southeastern California.

Grab and drag the slider to compare the the Anza-Borrego Desert basin before (left) and after (right) this winter's abundant precipitation. In both views, the irrigated fields within the community of Borrego Springs appear a lush green. The surrounding park is all bare ground and dormant vegetation in early fall, but following the winter wet season, a wash of green coasts both the canyon floors and the surrounding hillsides. Natural-color satellite image from the European Space Agency's Sentinel-2 satellite. Large versions: September 28, 2016 | March 12, 2017

After five years of drought, a wet winter

South of Palm Springs, the park is in California’s Climate Division 7—the Southeast Desert Basins—where the average winter precipitation is just shy of 3 inches (less than half of Los Angeles’ normal winter precipitation of 7 inches). While the 2016-17 winter precipitation in the division was not record-shattering, it was more than twice the normal amount, and—perhaps importantly—it followed the worst extended dry spell in the division’s historical record.

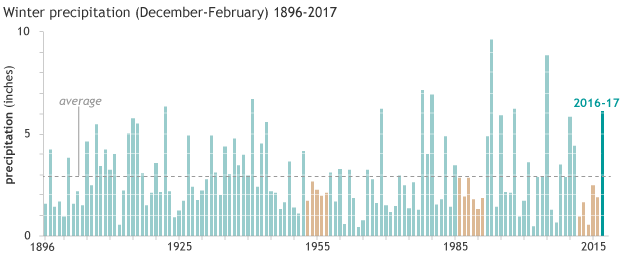

Winter precipitation (December-February) for California climate division 7 (Southeast Desert Basins) from 1895-96 to 2016-17. The average winter precipitation for the division is just under 3 inches (dashed line). Extended dry spells (five or more consecutive winter wet seasons with below-average precipitation) are colored brown. NOAA Climate.gov graph, based on data from NCEI Climate at a Glance tool.

Since 1896, the division has only experienced two other periods where precipitation during the winter wet season was below average for five years or more in a row: the five winters from 1952-53 through 1956-57, and the six winters from 1985-86 through 1990-91. While those periods might seem equal to the one that just ended, when we place these dry spells into an annual context, it becomes clear that the dry spell that began in the winter of 2011-12 was exceptional.

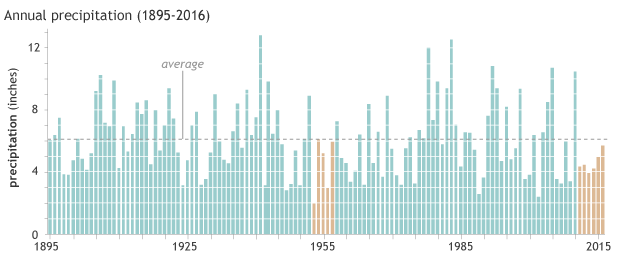

Annual precipitation for California climate division 7 (Southeast Desert Basins) from 1895-2016, with the dashed line indicating the average. The recent string of 5 years with below-average precipitation was the longest extended dry spell (brown bars) in the region's record. NOAA Climate.gov graph, based on data from the NCEI Climate at a Glance tool.

During the other long-running dry spells, rainfall outside of the winter months brought the annual total near or even above average in at least one year. The six consecutively dry winters of the late 1980s and early 1990s don’t even show up as an extended dry spell in the annual tallies. By comparison, the drought that started in 2011 brought six relentlessly dry and extremely hot years (four of the five hottest years on record for Southeast California occurred during the recent dry spell).

The 6.11 inches of precipitation that fell across California’s Southeast Desert Basins during the winter of 2016-17 was more than 200% of the division’s normal 2.97 inches. In addition, the Anza-Borrego desert basin received a “bonus” soaking rain event in early fall: a station in the park recorded just over 0.5 inches of rain on September 20. The rainfall may not have been record-breaking, but the patient seeds of the desert basins’ wildflowers had been waiting for that moisture for an unusually long time. As the warm, sunny days of March unfolded, the well-watered desert exploded in spectacular bloom.

Thanks to Jake Crouch of NCEI's Center for Weather and Climate and Jared Rennie of CICS-NC for their help obtaining station data for the Anza-Borrego Desert basin.