2017 Arctic Report Card: Arctic sea ice keeps getting younger and thinner

Details

Despite the fact that the area of the Arctic Ocean covered by sea ice during the winter maximum has declined only slightly in recent decades, the ice itself is profoundly different than it used to be. Very old ice—thick, strong, and more melt-resistant—has nearly vanished, and the amount of first-year ice—thin, salty, and unlikely to survive the summer—has skyrocketed.

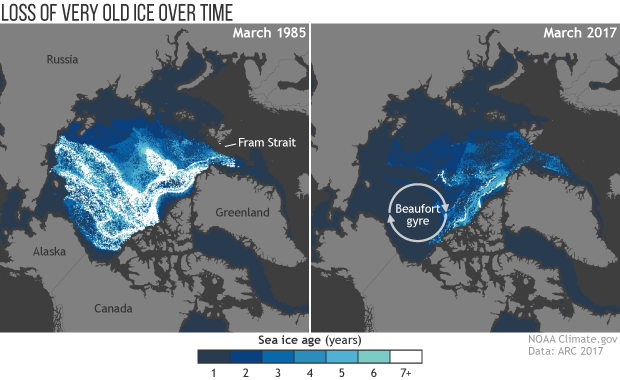

These satellite-based maps show the age of the ice in the Arctic at the end of winter in March 1985 (left) and March 2017 (right). The first age class on the scale (1, darkest blue) means "first-year ice,” which formed in the most recent winter. The oldest ice (>7, white) is ice that is more than seven winters old. Dark gray areas indicate open water or coastal regions where the spatial resolution of the data is coarser than the land map.

Historically, ocean currents exported old ice out of the Arctic through the Fram Strait, near Greenland. Meanwhile, multi-year ice continued to be built in the Beaufort Gyre, north of Alaska. Ice floes would circulate in that loop for many years, growing thicker and stronger. In many years during recent decades, however, the southern arm of the Beaufort Gyre is too warm for sea ice to survive. Multi-year ice is lost from the Arctic as it always has been, but it is being rebuilt at much slower rates.

As sea ice ages, it adds volume, expels salt, and is toughened up by jostling and collisions. Very old ice may be more than 10 feet thick. These characteristics make it better able to withstand warm weather and pounding from storm waves; its loss makes for a more fragile ice pack. As reported in the 2017 Arctic Report Card, sea ice older than four winters made up 16 percent of the Arctic sea ice pack in March 1985. In March 2017, it made up less than 1 percent. Meanwhile, first-year ice constituted roughly 55 percent of the Arctic sea ice pack in March through the 1980s. In March 2017, first-year ice comprised nearly 80 percent of the ice pack.

This large amount of young ice becomes self-reinforcing: it melts easily in the summer, leaving more open water exposed to sunlight during the Arctic’s long summer days. More solar heating raises ocean temperatures, which further impede ice growth. This feedback loop is helping to establish the small summer ice extents of the past decade as the new normal for the Arctic.

Maps by NOAA Climate.gov, adapted from Figure 3b in “Sea Ice” chapter of the 2017 Arctic Report Card, based on data provided by Mark Tschudi.

ARC 2017: Sea Ice