2019 Arctic Report Card: Old, thick ice barely survives in today’s Arctic

Details

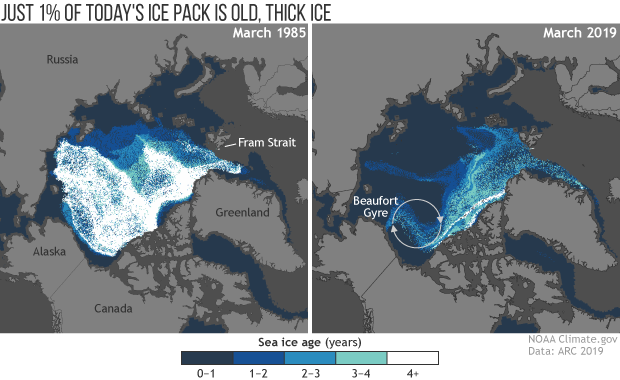

Arctic sea ice was older in 1985 than it is now. The Arctic hasn’t experienced a physics-defying time warp, but one consequence of the region’s dramatic warming trend is that Arctic sea ice doesn’t last as long as it used to. In March 1985, sea ice at least four years old made up 33 percent of the ice pack in the Arctic Ocean; in March 2019, ice that old made up 1.2 percent of the pack. Instead, more than three-quarters of the winter ice pack today consists of thin ice that is just a few months old, whereas in the past it was just over half.

Adapted from the 2019 Arctic Report Card, these color-coded maps show the age of sea ice in the Arctic ice pack during the third week of March 1985 (left) and March 2019 (right). Ice that is only one winter old is darkest blue. Ice that has survived at least four full years is white. Thirty-four years ago, a significant portion of the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean basins of far eastern Russia, Alaska, and Canada was at least four years old; as of March 2019, the oldest ice was largely confined to narrow ribbons along the northern coasts of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and Greenland. Ice less than a year old dominated the Arctic.

Over time, sea ice that survives the summer melt grows both thicker and less salty, which makes it more resistant to melt and storm-induced disintegration than thin, first-year ice. Historically, a looping current north of Alaska, known as the Beaufort Gyre, acted as a nursery for young ice where it could recirculate, thicken, and grow. Historically, ice growth in the Beaufort Gyre roughly offset the flow of ice out of the Arctic via the Fram Strait east of Greenland. In the past decade, however, summers in the southern portion of the gyre have been too warm for sea ice to survive. Old ice continues to exit the Arctic through Fram Strait, but very little is rebuilt.

This image is adapted from NOAA’s 2019 Arctic Report Card, which provides an annual update on observations from the Arctic, documenting changes in the physical environment—including sea ice, the atmosphere, snow, the Greenland Ice Sheet, and carbon stored and released by permafrost—and the impacts on people, plants, and animals that live there. This peer-reviewed collection of essays is part of NOAA’s mission to help the nation understand and prepare for the risks and opportunities of a changing climate.

Reference

Perovich, D., Meier, W., Tschudi, M., Farrell, S., Hendricks, S., Gerland, S., Kaleschke, L., Ricker, R., Tian-Kunze, X., Webster, M., Woods, K. (2019). Sea ice. 2019 Arctic Report Card.

Note: Over the years, the Arctic Report Card has listed varying figures reported for 1980s “old” sea ice, and these differences have been driven by multiple factors, such as changes in the year and week measured, and improvements to ice-motion models over time. The biggest measurement difference between the 2019 and 2018 Arctic Report Card (which estimates old ice in March 1985 at 16 percent) results from a change in the total area examined. The 2018 Arctic Report Card defined the total possible ice area to include the Bering Sea, Baffin Bay, Hudson Bay, and part of the Greenland Sea—areas where all sea ice is seasonal. The 2019 Arctic Report Card calculates the percentage of old ice only for the smaller geographic area where multiyear ice is historically known to have formed.