How El Niño and La Niña affect the winter jet stream and U.S. climate

Details

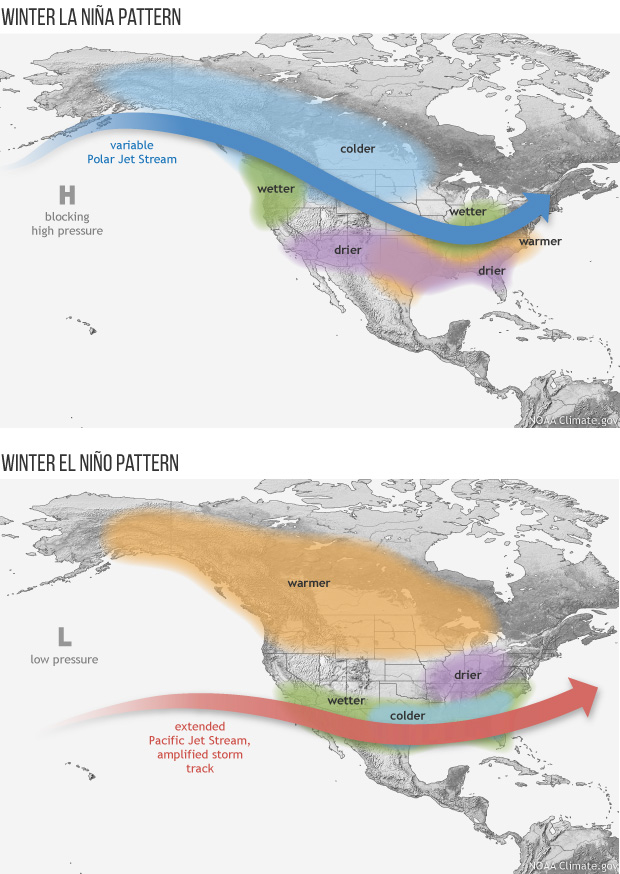

The arrival of El Niño or La Niña in the tropical Pacific Ocean triggers a cascade of changes in tropical rainfall and wind patterns that echo around the globe. For the United States, the most significant impact is a shift in the path of the mid-latitude jet streams. These swift, high-level winds play a major role in separating warm and cool air masses and steering storms from the Pacific across the U.S.

These maps illustrate the typical impacts of El Niño and La Niña on U.S. winter weather. During La Niña, the Pacific jet stream often meanders high into the North Pacific and and is less reliable across the southern tier of the United States. Southern and interior Alaska and the Pacific Northwest tend to be cooler and wetter than average, and the southern tier of U.S. states—from California to the Carolinas—tends to be warmer and drier than average. Farther north, the Ohio and Upper Mississippi River Valleys may be wetter than usual. During El Niño, these deviations from the average are approximately (but not exactly) reversed.

One or more of these climate patterns have occurred during many El Niño and La Niña events in the past. That doesn’t mean that all of these impacts happen during every episode. Every event is somewhat different. In other words, the influence of El Niño on U.S. winter climate is a matter of probability, not certainty.

El Niño and La Niña are opposite phases of a natural climate pattern across the tropical Pacific Ocean that swings back and forth every 3-7 years on average. El Niño and La Niña alternately warm and cool large areas of the tropical Pacific—the world’s largest ocean—which significantly influences where and how much it rains there.

Like a boulder dropped into a stream, this shift in the location of tropical rainfall disrupts the atmospheric circulation patterns that connect the tropics with the middle latitudes, which in turn modifies the mid-latitude jet streams. By modifying the jet streams, El Niño and La Niña can affect temperature and precipitation across the United States and other parts of the world. The influence on the U.S. is strongest during the winter (December-February), but it may linger into early spring.