Models warn of dustier summers in U.S. Southwest and Southern Plains, but Northern Plains may see fewer dust storms year round

Details

Dust storms on the scale of Black Sunday of the 1930s Dust Bowl may be a distant memory, but the U.S. Southwest and Great Plains still experience episodes of blowing dust that snarl transportation and threaten public health. These storms also spell trouble for the snowpack and water supply in the Rocky Mountains.

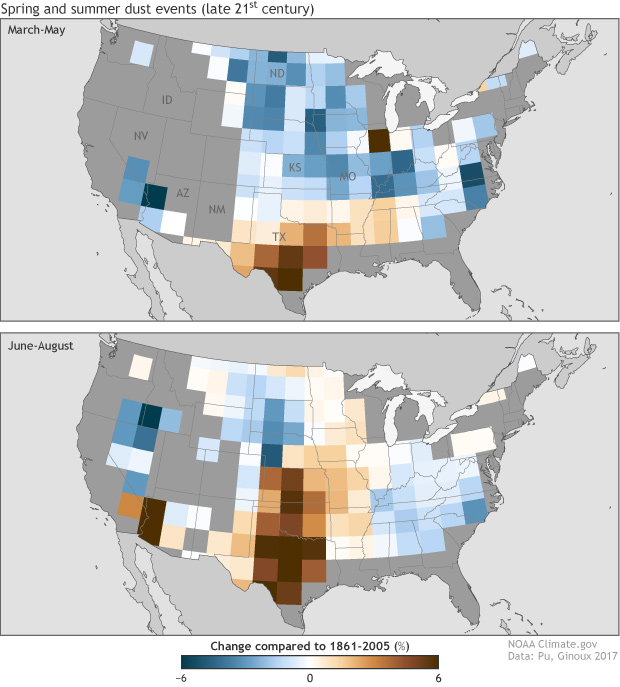

Preliminary NOAA modeling research found human-caused global warming is likely to have widely diverging impacts on U.S. dust storms, with significant increases in the Southwest and Southern Plains in warm months, but decreases year round in the Northern Plains. These maps show the projected increases (brown) or decreases (blue) in dust event frequency in spring (March-May) and summer (June-August) in the second half of the twenty-first century compared to historical conditions (1861-2005). The projections are based on the assumption that carbon dioxide emissions will continue to increase throughout the coming century.

Models projected dustier summers in Arizona and New Mexico as well as in the central and southern Great Plains from southern Kansas to Texas, mostly due to decreases in precipitation and increases in surface bareness due to less leafy vegetation. The projected increase in spring and summer dustiness in the Southern Plains is also linked to increases in surface winds, the result of an intensification of a powerful wind known as the Great Plains low-level jet.

On the other hand, springtime dustiness is projected to decrease across much of the Southwest, Nevada and southern Idaho, and in the Great Plains from North Dakota to Missouri. In most places, the improvements are linked to a combination of increasing precipitation and leafier vegetation resulting from an earlier start to the growing season.

The analysis used many different models, and the maps show the average of their results for a given location. The models agreed with one another better in some places and seasons than others. (See the original version of these maps for an indication of model agreement for each grid square). In general, places where the projected change was large—the Southwest and Southern Plains in summer, the Northern Plains in spring—had high model agreement.

When the model agreement was lower—such as across the Northern Plains in summer, and in the western edge of the Southern Plains in spring—it was mostly because the models disagreed about how warming will affect vegetation (first) and precipitation (a close second).

Among the limitations of the analysis was that the models did not include any possible changes in human-driven land use, such as deforestation or reforestation, urban growth, or changes in farming or grazing. Nor are these models able to simulate the sort of non-linear, “runaway” feedback loops between drought and dustiness that contributed to megadroughts across the West and Southern Plains in the past.

Despite these uncertainties, the research is an important early effort to identity which factors (precipitation, winds, and vegetation density) have the biggest influence on dust storms in different parts of the United at different times of year. Studies like this can help scientists prioritize future research, giving us the best chance of improving our ability to predict the impacts of human-caused global warming on dangerous and disruptive dust storms.

Reference

Pu, B., & Ginoux, P. (2017). Projection of American dustiness in the late 21st century due to climate change. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 5553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05431-9