Monitoring the Eyjafjallajökull Eruption

Details

Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull (pronounced “AY-yah-fyah-lah-YOH-kuul”) Volcano roared to life on April 14, 2010, injecting billowing clouds of steam and volcanic ash into the atmosphere. The hazards of flying through jet-engine-damaging clouds of volcanic ash prompted commercial airlines to cancel thousands of flights into and out of northwestern Europe. Could this volcano, which has caused such major disruptions in airline travel, also impact climate?

Powerful eruptions that occurred over the last century — Mt. Pinatubo, El Chichon, Mt. Agung and others — have shown that some volcanoes can explode with enough force to launch huge amounts of sulfur dioxide, ash, and other particles into the upper atmosphere, or stratosphere. Called aerosols, these particles reflect incoming sunlight, thereby exerting a cooling influence on Earth’s surface. Aerosols also absorb heat energy, so their long-term affect on temperature is complex. Because aerosols linger in the stratosphere, above the level where rain clouds form, their cooling influence can last for many months. For example, after the massive eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in 1991, which lofted an ash plume more than 20 kilometers into the atmosphere, Earth’s mean surface temperature decreased by about half a degree Celsius for over a year.

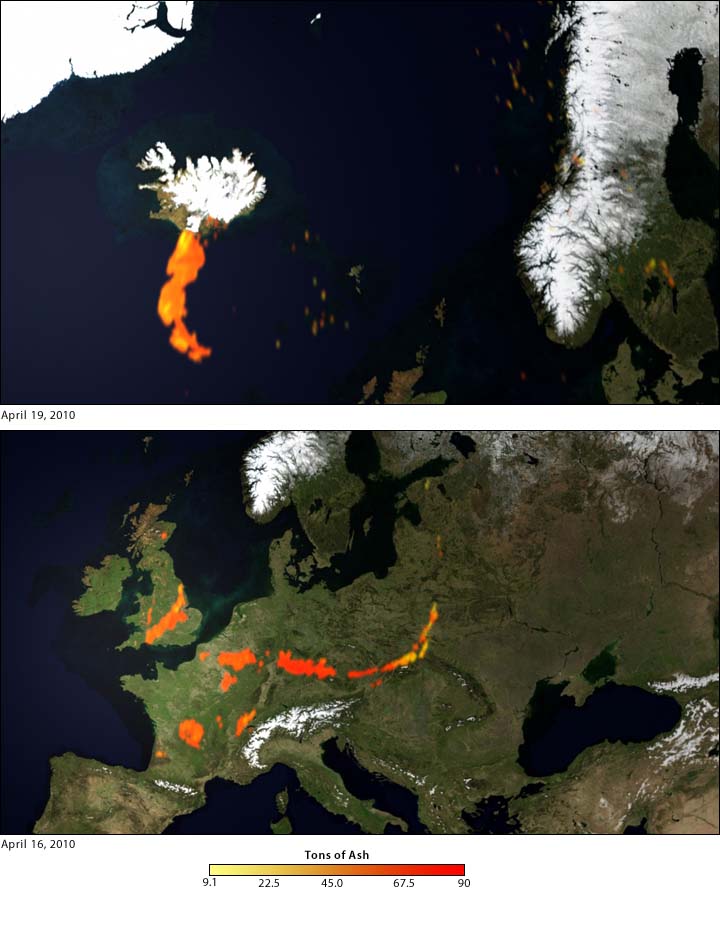

To better understand how much ash the volcano is releasing into the atmosphere and where it is going, NOAA scientists use data from a satellite sensor that can distinguish the ash from clouds. The image above shows concentrations of volcanic ash in the atmosphere in tons per square kilometer. The images, derived from the NASA’s Aqua/MODIS satellite sensor, show days-old clouds of ash moving across Europe on April 16 (bottom), and a plume of ash as it headed south from Iceland on April 19 (top).

Thus far, the data indicate that the eruption has not injected enough aerosols high enough into the atmosphere to result in any planetary cooling. Plumes of steam and ash rose up to heights of 10,000 meters on the first day of the eruption, but have since declined to around 6,000 meters in altitude. The ash cloud would have to reach a height of 10,500 meters — about 33,000 feet — to put aerosols into the stratosphere.

NOAA scientists say that based on the fact that the plume’s current height is not reaching the stratosphere, the volcano is not likely to have a large effect on global climate at this time. However, the last eruption of Eyjafjallajokull lasted for two years. It is still too early to know what the climate impacts might be if the eruption continues

NOAA scientists continue to monitor the volcano to ensure the safety of airplanes. NOAA operates two Volcanic Ash Advisory Centers that are part of a global network of nine centers. Learn more about how NOAA is tracking ash from the Iceland volcano.

References:

D. E. Parker, et. al; 1996. The Impact of Mt Pinatubo on Worldwide Temperatures; International Journal of Climatology, Vol. 16, 487-497

NASA’s Earth Observatory. (2000, September 5). Volcanoes and Climate Change.

NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory’s Volcanoes and Climate website

U.S. Geological Survey’s Volcanic Gases and their Effects website

An animation is also available.