Underwater Glider Completes Historic Trans-Atlantic Voyage

Details

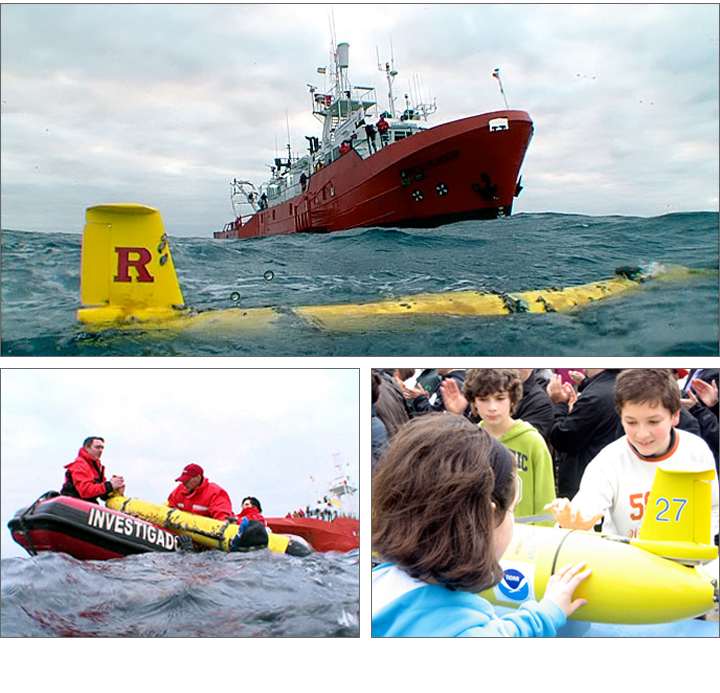

After traveling 7,300 miles over 221 days, the 7-foot-long Scarlet Knight aquatic glider was picked up off the coast of Spain in December by divers aboard the Spanish Vessel Investigador. It was the first unmanned underwater glider to successfully cross the Atlantic Ocean.

The ocean observing community celebrated the successful mission on December 9, in Baiona, Spain, the port town where Christopher Columbus’s crew announced the existence of the New World. In the bottom right photo, Spanish school children admire the 7-foot-long, 135-pound glider.

The glider’s journey — a joint research effort spearheaded by the U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS®), NOAA and Rutgers University — started roughly four years ago when NOAA Assistant Administrator for Oceanic and Atmospheric Research Dr. Rick Spinrad challenged Rutgers scientists and students to build a remote-controlled, deep-sea glider — “for the good of the country” — that can cross the Atlantic, continuously surveying the ocean’s depths.

The Rutgers team previously attempted to fly one of their gliders across the Atlantic in 2008. That glider was lost just off the coast of the Azores Islands. The team upgraded the second Scarlet Knight prototype, named after the Rutgers mascot, with a special coating to repel barnacles. It was also designed with a greater diving capability and better communications software. The improved glider was launched off the coast of New Jersey last April. Steered and operated remotely by student pilots at Rutgers, the glider managed to avoid boats, fishing nets and other obstacles during its voyage.

The glider does not use a propeller to provide forward thrust or motion. As it rides the currents, the glider dives by a remote-controlled mechanism that pumps water into a cup in its nose, causing it to “nosedive.” The unequal buoyancy between the nose and the glider’s body helps propel the glider downward. To ascend, water is pumped out the glider’s nose, allowing it to float upward.

The glider’s data-gathering capability holds much promise for improving our understanding of the ocean and its role in climate and weather. The glider repeatedly dove to depths of up to 200 meters to collect data on temperature, salinity and density, which are particularly sensitive to atmospheric warming and the buildup of greenhouse gases.

Scientists will be able to correlate these data with those from satellite imagery and altimetry, radar systems, and seafloor- and buoy-mounted sensors to get a more detailed view of a particular patch of the ocean. The glider’s constant motion offers a more comprehensive view of ocean conditions in time and space than the static measurements usually taken from the deck of a ship.

Related stories

Ocean Glider Set to Attempt Atlantic Crossing

Glider Completes Historic Ocean Crossing: New Technology Advances Climate Understanding

Top and bottom left photo taken by Rutgers diver Dan Crowell. View additional photos and listen to podcasts at the Rutgers University’s blog of the Scarlet Knight’s journey.