A conversation with Danielle Claar: NOAA Postdoc, marine scientist, diver

With this article, we continue Climate.gov’s series of interviews with current and former fellows in the NOAA Climate and Global Change Postdoctoral Program about the nature of their research funded by NOAA and what career and education highlights preceded and followed it.

Over the past 30 years, the Postdoctoral Program, funded by NOAA Climate Program Office, has hosted over 200 fellows. The Program’s purpose is to help create and train the next generation of researchers in climate science. Appointed fellows are hosted by mentoring scientists at U.S. universities and research institutions.

Our interview is with Danielle Claar, a current NOAA Climate and Global Change Postdoctoral Fellow working at the Wood Lab at University of Washington. Her fellowship research focuses on coral reef parasites as indicators of environmental change. Specifically, she is investigating how oceanographic drivers during the 2015/2016 El Niño influenced fish parasites.

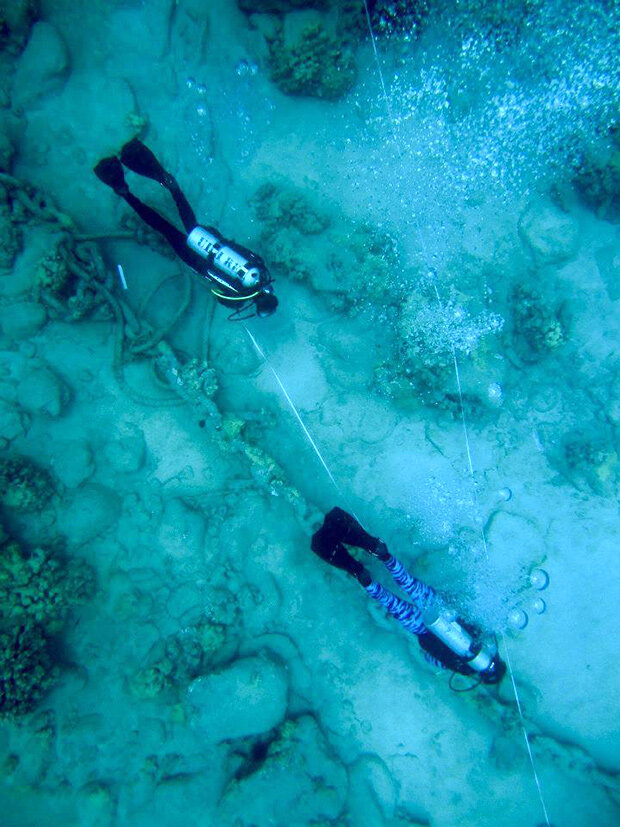

Danielle Claar on a research dive at Kiritimati (Christmas Island) in the tropical North Pacific. Photo courtesy Danielle Claar.

Claar’s complimentary interests in marine science and scuba diving have taken her to regions with extraordinary reef ecosystems, including Hawaii, Indonesia, and Kiritimati.

Our conversations follows.

When did you become interested in marine science? Was there a singular experience that drew you into the field?

I became interested in marine science at a young age. I was initially drawn to science because I have always been fascinated by how things work. Although I grew up in landlocked Idaho, our family traveled to the Pacific coast, where I fell in love with tide pool ecosystems filled with anemones, sea stars, and crabs. Additionally, my parents are avid scuba divers, and they took me diving for the first time when I was 12 years old. After graduating from high school, I decided to combine these two interests to pursue Marine Science at the University of Hawaii at Hilo.

Childhood trips to the Pacific Northwest coast fostered Claar's love of tide pool ecosystems. Photo by Danielle Claar.

When did you become certified in scuba diving? When did you do your first scientific diving?

I did my first coral reef dives on Maui when I was 12 years old and got certified in Mexico when I was 17. I became a scientific diver during my undergraduate degree in Hawaii, where I conducted projects to study the reef as well as the remains of a steamboat (SS Kauai) that was wrecked in 1913. I also earned my SCUBA Instructor certification while in Hawaii.

Divers drift over a massive chain on the seafloor, part of the wreck of the SS Kauai, a steamboat that went down in 1913 in what is today the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary. Photo courtesy Danielle Claar.

In summer 2011, you worked as a NOAA Hollings Scholar at NOAA Kasitsna Bay Laboratory in Alaska. What did you learn from that experience?

During my NOAA Hollings Internship at Kasitsna Bay, I studied long-term changes in intertidal communities (e.g., mussels, barnacles, tunicates) in relation to climate. I taught myself [the scientific software application] MATLAB during that summer, and I was able to delve into how to analyze time series data. This internship helped me understand how climate and ecology interact, and it was pivotal for me to learn how to code.

In summer 2011, Danielle worked as a Hollings Scholar at NOAA Kasitsna Bay Laboratory in Alaska. Photo courtesy Danielle Claar.

Just before your Ph.D. studies, you worked at Florida state government, at the Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve. What was the nature of your work there? What sort of citizen science initiatives did you work on?

At the Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve, I was an Environmental Specialist who focused on estuarine biology. I worked on multiple citizen science initiatives, including rookery monitoring of wading and diving birds. I also led a citizen science volunteer water-quality monitoring program that partnered with local individuals to consistently monitor water quality and the health of Estero Bay. I enjoyed working with the local community to monitor and protect the environment.

You began your Ph.D. studies at Canada’s University of Victoria in summer 2013. You studied the relationship between coral and its symbiotic algae at Kiritimati in the Pacific Ocean, the world’s largest atoll. You studied this topic through 2015 and 2016, years which saw a very powerful El Niño event. What did you learn from this research?

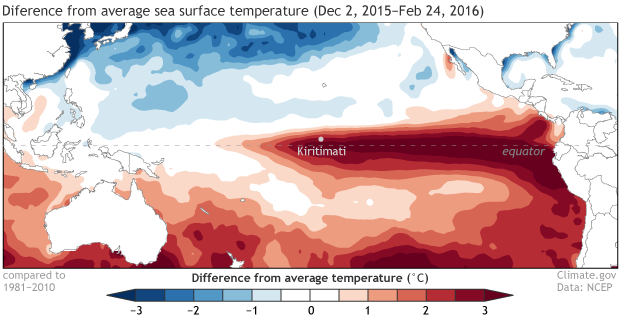

My Ph.D. began with the intention of understanding how local human disturbances, such as pollution and overfishing, interacted with the climate to influence coral symbioses, such as zooxanthellae. We knew that Kiritimati was located exactly in the middle of the Niño 3.4 region [the region used to monitor and describe El Niño strength], and that it was fairly likely an El Niño would occur during my Ph.D. studies.

Averaged weekly OISST sea surface temperature anomalies for the Pacific Ocean starting on the week of December 2, 2015 through the week of February 24, 2016. A historic El Niño lead to well above-normal ocean temperatures across the central and eastern Pacific Ocean leading to extensive damage to the coral reefs around the island of Kiritimati. Climate.gov map with data provided by the National Center for Environmental Prediction.

Of course, we couldn’t have known for sure that an El Niño would happen, or that it would produce the most extreme, prolonged heat stress measured to date. However, we tagged and sampled coral colonies in 2014 when the first signs suggested that an El Niño might occur.

A healthy reef at Kiritimati (Christmas) Island in the tropical North Pacific prior to the devastating bleaching event during the 2015-16 El Niño. Photo by Danielle Claar.

The 2015/2016 El Niño caused devastating coral loss across the Pacific, including up to 90% loss of coral cover at our study sites on Kiritimati Island. Although corals experienced an unprecedented 10 months of heat stress, some corals were able to survive this event. I studied coral symbioses in colonies before, during, and after this event, to understand what made these survivors unique. We found some corals that exhibited a remarkable recovery, and we were able to link this to patterns in symbiosis.

What was the most exciting part of the field work at Kiritimati? The most challenging?

The best part of my field work was the diving – experiencing the complex ecosystems that I study, and seeing the diversity of corals, fish, and invertebrates. There are two things that I found particularly challenging during my Ph.D. fieldwork. First, Kiritimati is a remote location (i.e., only one flight a week, no scientific field station), which made logistics tricky. Secondly, watching the effects of the 2015/2016 El Niño on the reef was devastating. I find hope in the “super corals” that survived, but seeing the major changes to a previously pristine reef was rather rough.

A diver swims above a coral reef that is dotted with stark white patches where corals experiencing heat stress have bleached. Photo by Danielle Claar.

What happens to reefs and reef algae during an El Niño event?

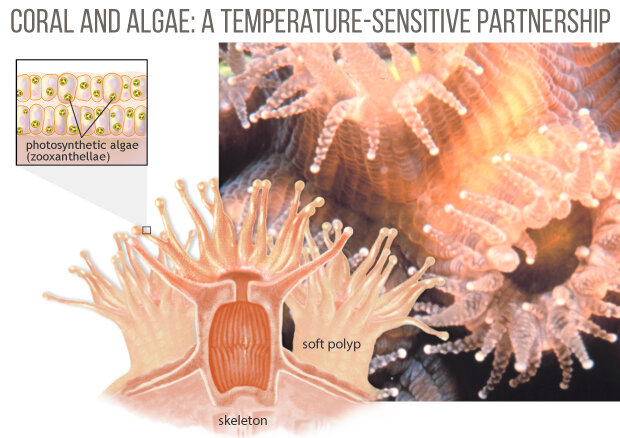

Corals live in symbiosis with Symbiodiniaceae, a type of algae which is also known as zooxanthellae. These symbionts live inside the coral cells and act like miniature solar panels, soaking up sunlight and turning it to energy that the coral can use to live and grow. Warming breaks down this vital symbiosis, and the coral expels its symbionts, causing bleaching. Marine heatwaves can cause coral bleaching, and the impact of a heatwave is dependent on its duration and magnitude.

Coral are animals that partner with single-celled algae (zooxanthellae). During times of temperature or other stress, the collaboration can break down, causing the coral to expel their colorful symbionts. If harsh conditions persist too long, the bleached corals starve. NOAA Climate.gov graphic, using a photo by Brent Deuel, from NOAA Photo Library on Flickr.

Your current NOAA-funded postdoc research focuses on using coral reef fish parasites as bioindicators of El Niño. Can you talk about what your research has found thus far?

I am currently studying the parasite communities of fish sampled in the Central Pacific both before and after the major 2015/2016 El Niño event. The goal of this project is to investigate how climate oscillations influence parasitism, and how we can use this to understand the impacts of heatwaves on marine communities. If we see large changes in parasite communities after a warming event like El Niño, we know that warming impacts are probably significant for that ecosystem.

We are currently in the fish dissection phase of this project and will be starting analyses early next year. Stay tuned for more soon!

How did you hear about the C&GC Postdoctoral Program Fellowship? What aspect of your research are you looking forward to most during your Fellowship?

I heard about this fellowship program through colleagues. I am thrilled to combine climate and ecology to better understand how climate oscillations and change shape ecosystems people rely upon.

How does your research on corals relate to reef conservation?

As scientists and policymakers work together to come up with strategies for protecting coral reefs, it is important to understand when and why some corals persist while others do not. My research helps us understand how climate influences ecological interactions, and also how local protection may enhance coral survival during extreme heatwaves.

Any specific guidance you would give to fellow scuba divers for protecting the reefs they love?

I'd say: work to reduce your carbon emissions and support dive operations that are environmentally conscious. Some dive operations work hard to educate their divers about the local environment and teach new divers to take only pictures and leave only bubbles—those are the type I recommend.

What is your favorite place to dive and why?

Everywhere I've gone diving I've enjoyed, because there's always something new and interesting to learn about and explore. My best dive trip so far, though, was probably my honeymoon with my husband to Raja Ampat, an Indonesian archipelago. The coral and fish diversity there are absolutely phenomenal, and the reefs are breathtaking.