In the face of sea level rise, NOAA helps endangered Hawaiian monk seals find higher ground

Honey Girl (Part 1)

One calm morning on O’ahu, Hawai’i, wildlife veterinarian Dr. Michelle Barbieri received a phone call. It was November 2012, her second month on the job, and a scrawny monk seal had just hauled out on a beach with a wire leader—a short length of metal wire that attaches fishing line to a baited hook—tangled up in its mouth. Along with a team of expert monk seal responders and scientists, Dr. Barbieri drove out to evaluate the starving animal. The team knew that this seal—ID’d with the tag ‘R5AY’—was no ordinary individual. Locals had taken to calling her “Honey Girl”, a term often used as a nickname in Hawai’i.

”She was this prolific mom who gave birth consistently every single year,” says Dr. Barbieri, now lead of NOAA’s Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program. “We discovered so many stories about how much she means to people and how important she is to continuing the monk seal population.”

The surgery to remove the wire was ultimately successful, but left Honey Girl with a new challenge—learning how to eat with only half of her tongue remaining. “Monk seals often use their tongue for suction when they eat,” Dr. Barbieri explained, “so we didn’t know if she was a releasable seal, if she would ever succeed in the wild again.”

Honey Girl may have been unique, but her unfortunate accident was not. From 1976 to 2018 there were 180 reports of Hawaiian monk seals becoming hooked by fishing gear or entangled in nets. Of those incidents, 19 were fatal. Hawaiian monk seals are impacted by dozens of other threats, many of them human-caused. However, NOAA’s science-based conservation and management programs have allowed Hawaiian monk seal populations to make positive strides forward in the past few years, despite increasing human and natural threats.

Monk Seal Habitat

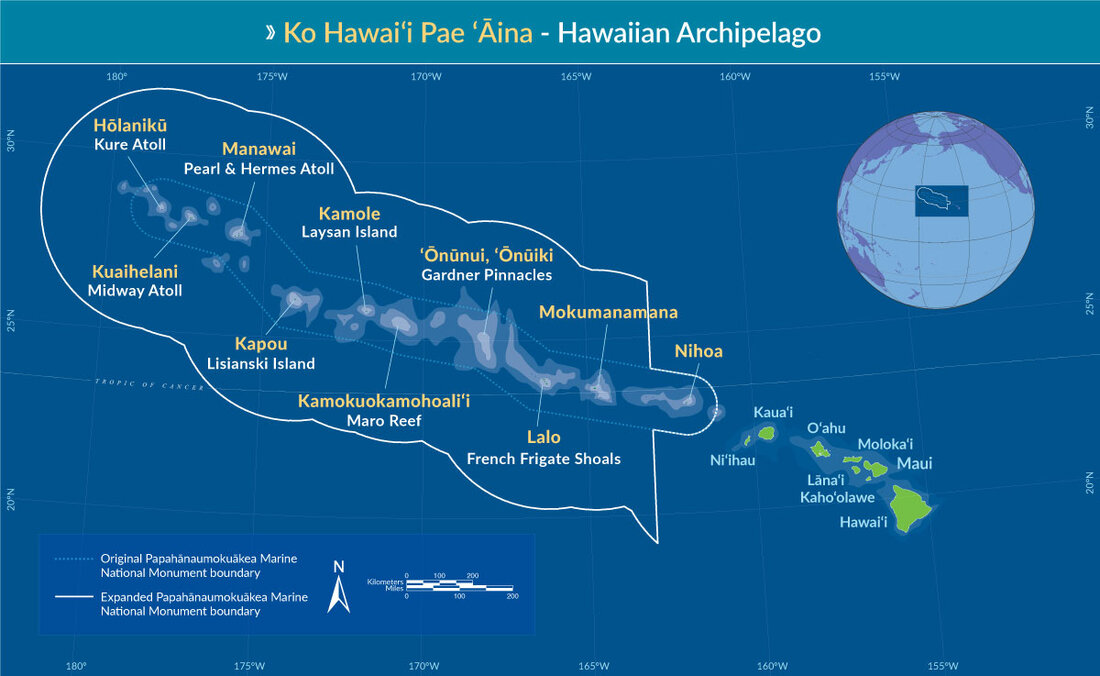

Hawaiian monk seals thrive in the warm, subtropical waters surrounding the Hawaiian archipelago (Ko Hawai’i Pae ‘Aina). The islands and atolls are scattered diagonally across a distance of 1,500 miles and are organized in two main regions: the main Hawaiian Islands and the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Most of the surviving population of Hawaiian monk seals inhabit the Northwest Hawaiian Islands Archipelago, which the native Hawaiians call Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina . Map courtesy of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

The main Hawaiian Islands span from Hawai’i Island, the largest and farthest east, to Kaua’i and Ni’ihau, and are inhabited by around 1.5 million people. The more remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, reaching from Nihoa all the way out to Kure Atoll (Hōlanikū), comprise Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and are largely uninhabited by humans, save for a handful of resource managers and conservationists from agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources.

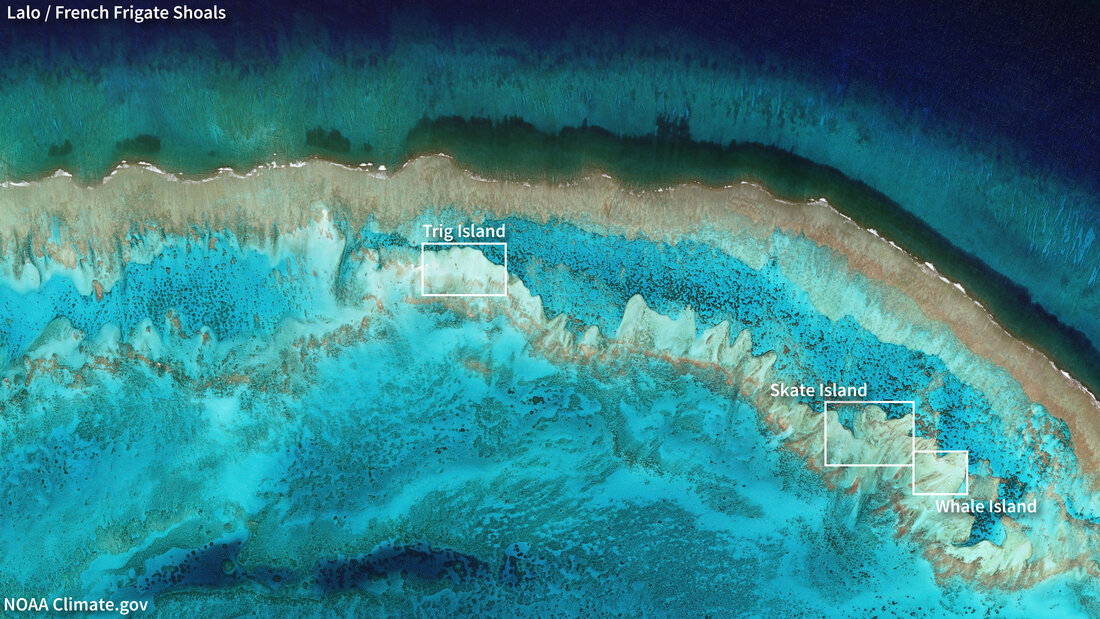

The low-lying sandbars and islands within an atoll known as the French Frigate Shoals in English and Lalo in the native Hawaiian language are critical habitat for the seals. NOAA Climate.gov animation based on NASA Blue Marble data and Sentinel imagery from the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Around 1,200 Hawaiian monk seals—the majority of the current population—occupy the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. In the past few decades, however, a population of about 350-400 individuals has recolonized the Main Hawaiian Islands. The majority of a monk seal’s time is spent at sea, patrolling the seafloor for fish, octopus, and crustaceans. When it comes time to rest, molt, and give birth to their pups (also referred to as ‘pupping’) monk seals seek sandy stretches of shoreline as “haul-out” sites. These beaches are crucial havens for pupping, socialization, and avoiding predator encounters.

A juvenile Hawaiian monk seal in the clear waters of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument on July 5, 2015. NOAA photo courtesy the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument Flickr photostream. Used under a Creative Commons license.

Threats and Vulnerability

Genetic evidence indicates that Hawaiian monk seals have occupied the archipelago for millions of years. They are one of only two mammal species endemic to present-day Hawai’i that occupied the islands before the arrival of humans, hinting at their incredible resilience to change. However, the species is far from invincible. Currently, the species is classified as ‘Endangered’ by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and has been protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act since 1976.

Given the stark difference in human habitation between the two “halves” of the Hawaiian archipelago, the specific threats to a monk seal vary depending on its location. The growing population of monk seals in the main Hawaiian Islands struggle with more direct human threats, such as fishery interactions (resulting in hookings and drowning), intentional killings, and the inherent risk of sharing beaches with eager tourists who might venture a little too close.

A young Hawaiian monk seal (ilioholokauaua in Hawaiian) rests on a floating mattress of tangled fishing nets on October 21, 2014. Flickr photo by the Marine Debris Team of the NOAA Coral Reef Ecosystem Program.

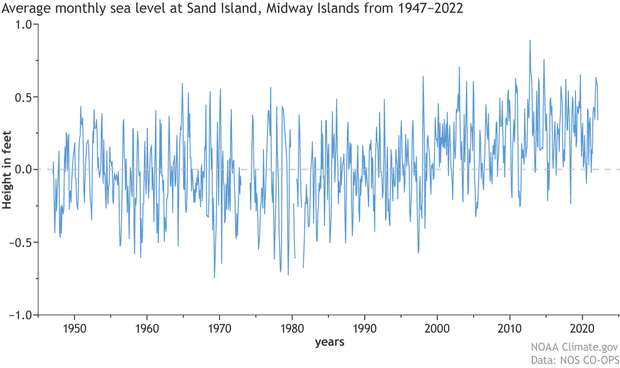

In the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, which are more remote and distanced from most direct human interactions, prevalent issues include entanglement in marine debris and starvation due to limited availability of prey. However, a growing threat to the monk seal populations in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands is sea level rise, which is eroding the shoreline, submerging their pupping beaches, and increasing the frequency of predatory shark encounters. Current rising sea levels are linked to our changing climate. By 2050, sea levels along the coastline of the Hawaiian Islands are projected to rise an average of 6 to 8 inches.

East of Tern Island, Trig, Whale, and Skate Islands were once the primary birthing spots for endangered Hawaiian monk seals at Lalo (French Frigate Shoals). They were submerged by rising sea level over the past few decades. Seals were forced to shift to locations with less protection from predators like sharks. NOAA image from How to Save an Island story map.

Dangers of Disappearing Beaches

There are many ways in which climate change is potentially impacting Hawaiian monk seals, but some of these connections are not entirely clear to experts yet. Because climate change often affects ecosystems from the bottom up, it can take years of monitoring to detect definitive patterns. “We do, however, have one truly existential threat from climate, which is loss of terrestrial habitat,” says Dr. Jason Baker, a marine biologist with NOAA’s Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center (PIFSC) and an expert in monk seal population dynamics. “While we could talk about a lot of speculative things, this is really happening right in front of our eyes, and it's a really big problem.”

Monthly sea level at Midway Atoll from 1947–2022 compared to the station datum (base elevation). NOAA Climate.gov image, based on data from the NOAA Tides and Currents webpage.

Seals rely on the shore not only as a refuge from predators, like sharks, but also as nurseries where they can safely birth and nurse their pups. They select beaches that are very well protected, usually with shallow reef areas just offshore to deter larger sharks and avoid intense wave action that might sweep small pups away. However, storms of increasing intensity and rising sea levels are causing many of these safe havens to disappear into the sea.

The erosion of islands within French Frigate Shoals (Lalo), an atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, is a prime example of this issue. Beginning in the late 90s, some of the largest islands in the atoll began to wash away. “We started seeing Galapagos sharks—a medium sized shark but big enough to kill seal pups—coming in,” explains Dr. Baker. “They were killing 20-30% of the pups that were born at French Frigate Shoals, which at the time was the largest population of monk seals.”

East Island, pictured here in 2018, is one of many low-lying islands in the Lalo atoll (French Frigate Shoals in English) that are being lost to sea level rise. Photo courtesy Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument; used with permission.

Shark predation is just one consequence of monk seal habitat degradation. In recent years, more pups have been lost at sea during high tides and storms with high surf. By 2018, three of the main pupping islands at French Frigate Shoals had been mostly or entirely submerged due to gradual erosion and hurricanes. “It was unprecedented,'' says Dr. Baker. “There's a lot at stake when it comes to habitat loss, and we know that the erosion we're seeing at French Frigate Shoals will eventually happen at other sites as well.”

Already eroding due to sea level rise, East Island was dealt a final blow in 2018, when it was erased by Hurricane Walaka. Since then, a small sand spit has re-accumulated. Image from NOAA fisheries.

Relocating Seals

Dr. Baker works directly with the Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program to process and analyze data collected by field teams, scanning for positive and negative indicators of monk seal population health. “We'll look at changed trends in abundance and at age-specific survival rates throughout the monk seal’s range so we can see if there are particular areas where there's low juvenile survival, which is usually one of our first signs of a problem,” Dr. Baker explains. Once an issue is identified, an intervention plan can be designed, and its progress monitored.

The threats to young seals at French Frigate Shoals inspired new conservation strategies, such as translocation, or the “the deliberate movement of organisms from one site for release in another.” This technique has been used as a management and conservation tool for terrestrial wildlife since the 1800s, but its application to marine mammals is fairly novel. Monk seal translocation decisions are based on recent survival rate data. Once pups born in vulnerable areas are weaned from their mothers, field teams transport them to sites with more favorable conditions and demonstrably higher survival rates. Conservationists on NOAA’s field expeditions have successfully translocated about 400 Hawaiian monk seals since the 1980s.

Despite its current and historical successes however, translocation may not be a viable solution indefinitely. Rising sea levels over the next 30 years will further increase the reach of high tides and storm surges. Damages will vary in severity, depending on factors like local weather, erosion, land subsidence, and the global sea level rise scenario, which is dictated by climate change. Early estimates under a median sea level rise scenario (48 cm rise) foreshadow the enormous loss of between 15 and 65 percent of land surface area at sites like French Frigate Shoals and Pearl and Hermes Reef (Manawai) by the end of the century. Under a maximum sea level rise scenario, some of the islets could disappear almost entirely— a devastating loss of habitat for not only Hawaiian monk seals, but also for several seabird species and the threatened Hawaiian green sea turtle.

A Hawaiian monk seal / ilioholokauaua (Neomonachus schauinslandi) and green sea turtle / honu (Chelonia mydas) resting on the beach in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument on July 17, 2007. Photo by Mark Sullivan, NOAA Fisheries Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program. Used under a Creative Commons license.

“The ultimate solution, of course, would be if climate change were to reverse and we stopped losing habitat. But even with the most ambitious climate mitigation goals, it's going to be a long, long time before this ship slows down and starts to turn around,” Dr. Baker acknowledges. “It's all going to hinge on the success of island preservation and restoration. We want to do mitigation on the ground that will preserve habitat for seals, but that is complicated and expensive. The best approach has not yet been identified.”

NOAA’s commitment to monk seal conservation is paying off

Despite discouraging climate trends, intensive planning and implementation of conservation actions have helped Hawaiian monk seal numbers to rebound significantly, the upward trend beginning in earnest around 2013. Although a full recovery of the species is a long way off, there have been some relatively recent, encouraging developments. The overall population has seen a consistently positive growth trend of 2% every year between 2013 and 2021. Currently, the Hawaiian monk seal population is estimated to be around 1,570 strong—the first time in over twenty years that the species has surpassed 1,500.

Working to combat the scope of threats to Hawaiian monk seals requires a coordinated, collaborative effort. NOAA takes an admirably thorough approach to conservation, their work informed by science and executed by experts. Under the umbrella of NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service operates the regional Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, which houses the Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program. These departments work together to design and implement large-scale conservation solutions.

The agency’s recovery planning process for Hawaiian monk seals is designed to holistically address threats of both the ecological and human-caused variety. In addition to the work being done by Dr. Barbieri and Dr. Baker, examples of active conservation and management strategies conducted by NOAA and its partners include: protecting habitat, reducing human-seal interactions, responding to monk seal strandings, translocating pups to safer areas, providing outreach and education, and much more.

NOAA has developed strategic implementation plans that focus on partnerships and collaboration, and on issues affecting the main Hawaiian Islands monk seal population specifically. These plans include the Recovery Plan for the Hawaiian Monk Seal published in 2007, the Main Hawaiian Islands Monk Seal Management Plan released in 2016, and the Species in the Spotlight Priority Actions: 2021-2025 released in 2021. These existing, forward-looking strategic documents will continue to inform research and conservation efforts in the coming years, with the ultimate goal of securing the long-term success of the species.

Honey Girl (Part 2)

Weeks had gone by since Honey Girl’s surgery, and the rehabilitation team finally succeeded in getting her to eat, and adjust to life with the scarred remains of her tongue. Despite being under the usual benchmark weight for release, Honey Girl was allowed to return back to the wild soon after her appetite returned. “Ordinarily we would want a seal to gain more weight before release,” Dr. Barbieri explains. “But with her experience as a successful forager, our thorough knowledge of monk seal patterns around the islands, and the fact that so many people were really invested in Honey Girl, we figured we could monitor her health from the shore with the help of the community to make sure she's putting weight back on in the wild.”

A couple of weeks later, Dr. Barbieri got another phone call. Honey Girl had been spotted on the shore, unresponsive and no plumper than when she was released weeks before. The team headed down to the beach, prepared to readmit the seal into veterinary care and reassess her health. But as they began to coax her into a transport cage, Honey Girl began to protest cheekily, her sluggish demeanor gone.

The Hawaiian monk seal designated R5AY—nicknamed Honey Girl by locals—with pup RF20 in November 2014. Honey Girl nearly starved to death in 2012 when she was hooked through the lip by abandoned fishing line that was tethered to the bottom of the ocean. Photo by NOAA Fisheries.

“It was like she flipped a switch,” Dr. Barbieri recalls. “She started moving around and looked at us like, ‘Oh, heck no! What are you doing?’” Closer examination from a different angle revealed that she had actually put on weight and—since she was clearly in good spirits—Dr. Barbieri and the team backed away and left her to sunbathe. The following year, Honey Girl mothered another healthy pup, and continued pupping consistently until she passed away in 2020.

Read more about Honey Girl's conservation story, explore the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument through its amazing photo galleries, or listen to Michelle Barbieri talk about her work to protect monk seals in NOAA Fisheries' podcast.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to NOAA experts Dr. Jason Baker, Dr. Michelle Barbieri, and Dr. William Sweet for contributing their knowledge, research, and first-hand experiences to this article.

Safety & Educational Resources

- Read more about the Hawaiian monk seal

- Threats to Hawaiian monk seals

- Stay informed with Hawaiian monk seal news and updates

- Report stranded seals or other marine mammals

- Safely and respectfully observe marine wildlife with this easy guide

References

Climate Change Impacts on Ecosystems. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2018).Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.epa.gov/climateimpacts/climate-change-impacts-ecosystems

Hawaiian Monk Seal. Marine Mammal Commission. (2022, August 30). Retrieved September 2022, from https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/species-of-concern/hawaiian-monk-seal/

Hawaiian Monk Seal. NOAA Fisheries. (2022, September 15). Retrieved August 2022, from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/hawaiian-monk-seal

Hawaiian Monk Seal Conservation & Management. NOAA Fisheries. (2022, September 15). Retrieved September 2022, from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/hawaiian-monk-seal#conservation-management

Hawaiian monk seal translocation project improves survival. NOAA Fisheries. (2020, August 28). Retrieved September 2022, from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/hawaiian-monk-seal-translocation-project-improves-survival

Hawaiian monk seal population surpasses 1,500! NOAA Fisheries. (2022, May 9). Retrieved August 2022, from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/hawaiian-monk-seal-population-surpasses-1500

NASA Sea Level Change Portal. NASA. (2022, February 15). Retrieved September 2022, from https://sealevel.nasa.gov/task-force-scenario-tool/

Pacific Islands. NASA Sea Level Change Portal. (2022, February 15). Retrieved September 2022, from https://sealevel.nasa.gov/task-force-scenario-tool/?type=regional®ion=PAC

R5AY: Honey Girl's story of Struggle and salvation in Paradise. NOAA Fisheries. (July 2017) Retrieved January 2023, from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/r5ay-honey-girls-story-struggle-and-salvation-paradise

Threats to Hawaiian Monk Seals. Marine Mammal Commission. (2022, August 30). Retrieved August 2022, from https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/species-of-concern/hawaiian-monk-seal/threats-to-hawaiian-monk-seals/

Academic and Government Reports

Baker, J. D., Harting, A. L., Johanos, T. C., London, J. M., Barbieri, M. M., Littnan, C. L., & U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, Pacific Islands Region; Western Pacific Fishery Management Council (U.S.). (2020). (tech.). Terrestrial habitat loss and the long-term viability of the French Frigate Shoals Hawaiian monk seal subpopulation. Retrieved from https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/26090.

Baker, J. D., Littnan, C. L., & Johnston, D. W. (2006). Potential effects of sea level rise on the terrestrial habitats of endangered and endemic megafauna in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Endangered Species Research, 2, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr002021.

Codiga, D. & Wager, K. Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Land Use in Hawai‘i: A Policy Tool Kit for State and Local Governments. 2011. Center for Island Climate Adaptation and Policy. Honolulu, HI. Available at http://icap.seagrant.soest.hawaii.edu/icap-publications

Harting, A. L., Barbieri, M. M., Baker, J. D., Mercer, T. A., Johanos, T. C., Robinson, S. J., Littnan, C. L., Colegrove, K. M., & Rotstein, D. S. (2020). Population-level impacts of natural and anthropogenic causes-of-death for Hawaiian monk seals in the main Hawaiian Islands. Marine Mammal Science, 37(1), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12742.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminstration. (2022, February 15). 2022 Sea Level Rise Technical Report. National Ocean Service. Retrieved October 2022, from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/hazards/sealevelrise/sealevelrise-tech-report.html

Vogt, C. (2018). (tech.). Hawaiian Islands National Shoreline Management Study. United States. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 2022, from https://usace.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16021coll2/id/2963/.