How my job as a family doctor allows me to help my community face the climate crisis

This is a guest post by Dr. Anne Getzin, a family physician and graduate of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Climate and Health Science Policy Fellowship, supported by the Climate and Health Foundation. During the course of her fellowship, Anne partnered with the NOAA Climate Program Office to explore models for education and communities of practice to improve health professionals’ exposure to and familiarity with the dynamic interplay between climate, the environment, and human health.

Though I was already late for work, I sat a few minutes longer to listen to the radio in the hospital parking lot. It was a frigid January morning in Milwaukee and I was scheduled for a busy day at our family medicine clinic. The news story arresting my attention was reporting on the impacts of warming temperatures on an ecosystem across the world. Scientists found that “virtually no male turtles” were hatched in a warming breeding ground for green sea turtles in the Great Barrier Reef. The sex of sea turtles is, in part, determined by the temperature of the egg during incubation. The new study showed that over 99% of the sea turtles hatched were females in the much-warmer-than-normal breeding grounds. The shift in environmental dynamics presents an existential threat if temperatures—driven by global warming—rise faster than the turtles can adapt.

As a new mom myself, this news on the threat of irreversible biodiversity loss felt particularly heavy in the pit of my stomach. Tears welled up alongside a sense of dread about how fast the world my two daughters are growing up in is changing. I remembered the fear I felt as a child when I learned how human-made chemicals were destroying Earth’s stratospheric ozone layer, which protects all life from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays. Transported back to my eight-year-old self, I recalled wearing an Earth Day t-shirt depicting the hole in the ozone layer with white and hot pink puff paint on a teal blue background. I felt powerless as a kid but believed grown-ups would find a solution, if they paid attention. I wore the t-shirt, feeling that was how I could do my part. Ultimately, global society did find a way to start healing the ozone layer.

Human emissions of chemicals that deplete the ozone layer—the layer of the atmosphere that protects life on Earth from ultraviolet radiation—dropped sharply in the 1990s following the Montreal Protocol. NOAA Climate.gov image adapted from original by Our World in Data.

A drive to problem-solve in the face of distress has always been wired into my mindset. This drive is what led me to choose a career in medicine. However, as I headed in to work that day, trudging across the ice- and salt-encrusted parking lot, I felt deflated and powerless. I was the adult now, but I couldn’t see a path to healing. What could I do as a family doctor in Wisconsin to address the daunting problem of global warming?

Amid the bustling pace of family medicine (delivering babies and treating diabetes and everything in between) and early motherhood (kissing scraped knees and bedtime stories and snuggles), it would take a few more years of doom scrolling news headlines and reading the latest climate research before I stumbled onto Yale University’s online certificate program on climate change and health.

Could this be the path to healing that I was seeking—becoming a “climate doctor”?

Lessons from the COVID pandemic

At first, it seemed ill-advised to try tackling a graduate-level online course above and beyond my already overloaded work schedule. It was the summer of 2021, and I was exhausted. With the rest of the medical community, I was just coming up for air after navigating the chaos of the first wave of the COVID pandemic, only to face wave after wave of new variants as well as other health impacts of the pandemic—including worsened mental health, substance abuse, missed cancer screenings, debilitating effects of long COVID, and more.

But even amid the exhaustion, I recognized how I could apply lessons I learned from the COVID pandemic to the climate crisis, and I began to find hope. In the early days of the pandemic, we were playing defense and our health care systems were overwhelmed. We rushed to treat patients while conducting research, while learning about the rapidly evolving new disease in real time. But later, with more knowledge on transmission, adequate masks, at-home COVID tests, the advent of vaccines, and better communication strategies, we gradually shifted our efforts from treating symptoms to preventing infections. Elevating the importance of safe and healthy environments at home and work, we were able to integrate COVID prevention into the bigger picture of comprehensive wellness strategies for our patients and communities.

The pandemic was also a powerful reminder to me that as a medical student and physician, I trained and practiced skills to respond in times of crisis. Navigating the COVID pandemic as a family doctor and medical director forced me to refine those skills. I developed a sense of empowerment and a capacity to lean in and fully face disaster while acting to prevent further destabilization. Doctors are already called to respond to disasters caused by extreme weather and wildfires. If I—and other doctors—had more training, we could anticipate and plan to better manage and prevent changing health impacts due to global warming, and not just react to them in a pandemic-like crisis mode.

The connections between climate change and human health

In medical school and residency, we learned that environmental health and human health go hand-in-hand, but exploring the human health impacts of a rapidly changing environment driven by global warming had never been part of the discussion. So my next step on the path to becoming a climate doctor was to enroll in a year-long physician fellowship in climate and health science policy at the University of Colorado.

As I learned more about the intricate interactions between global warming, the environment, and human health, a veil was lifted. Now, I see clearly how climate-driven extreme events—such as heat waves, severe storms, floods, droughts, and wildfires—are increasingly harming both human and natural environments. Now I understand why these health hazards and others—such as poor air quality and the spread of insect-borne diseases—are very likely to worsen this century due to the buildup of human-emitted heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere (like carbon dioxide and methane). The threat of global warming brings a clear and present danger to human health and well-being.

Part of the hurricane preparedness plan for Tampa General Hospital—the region's only Level 1 Trauma Center—includes the deployment of a temporary sea wall capable of keeping out storm surge up to 15 feet. The wall is shown here protecting the hospital from surge associated with Hurricane Helene on September 26, 2024. Image courtesy AquaFence. Used with permission.

I learned about new tools and actions we can take to protect our health. For example, I studied temperature maps that reveal urban heat islands in Milwaukee, and I saw that the same disenfranchised communities that suffer the worst health equity gaps also face the highest heat exposure in the city, threatening physical and mental health further. I was encouraged to learn that solutions, like increased tree canopy, are associated with a multitude of health benefits. Trees help cool their immediate surroundings by providing shade and through evapotranspiration—much like how sweating helps to cool our bodies on hot days. And, research shows, trees offer other benefits such as reducing flash flood risk and lowering rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes and asthma.

Kids play in a fountain in Battery Park, New York, on June 16, 2012. Many urban areas are working to increase tree cover and provide cooling features to help residents cope with extreme heat. Adapted from original photo by S.L. Used under a Creative Commons license.

I also learned about new opportunities for physicians to expand their knowledge base and develop systems and skills to meet the new health challenges presented by rapidly changing threats like heat and extreme weather. With these tools, here are four ways physicians can lead the way in protecting the health of our communities in the face of global warming and climate change:

1. In the exam room

Clinicians need to recognize increased prevalence of climate-driven exposures in their communities, such as wildfires, that affect their patients’ health. Three major ones are air quality, allergy season, and insect-borne diseases. For example, when Canadian wildfire smoke blew into Wisconsin in the summer of 2023, it caught local physicians on their heels. In an area not typically affected by wildfires, many clinicians were not practiced in counseling on health protection due to severely degraded air quality. My colleagues rapidly learned about and then taught patients how to use the Air Quality Index and how to build inexpensive HEPA air filters for their homes.

A screenshot of the AirNow.gov Fire and Smoke Map showing the location of smoke (gray shading) and air quality conditions at monitoring stations (dots) on June 28, 2023. Smoke from fires in Canada pushed particle pollution in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley region into the range considered "unhealthy" (red dots) and "very unhealthy" (purple dots). Image from the Environmental Protection Agency AirNow.gov website.

Spring and Fall seasons are getting warmer, bringing longer and stronger allergy seasons that cause more suffering from itchy, watery eyes, runny noses, and asthma flares. Clinicians can educate their patients on why their symptoms are getting worse, and how to protect themselves. Changes in temperatures and the length of growing seasons will allow mosquitoes, ticks, and other pests to carry diseases (like West Nile Virus, Lyme disease, alpha gal syndrome, dengue, and malaria) into new geographic regions. Greater exposure to infectious diseases means physicians may need to recognize signs and symptoms of illnesses that were previously not part of their day-to-day routine.

2. Teaching and training our current and next generation of physicians

More education opportunities and peer-support initiatives are needed to help health professionals prepare for the myriad of health challenges caused by climate change. I am now teaching a cohort of current and future physicians about the causes and effects of global warming, and helping them to connect the dots just like I did. Global warming is not some abstract threat far away or far in the future; rather, its impacts are being felt today in every economic sector all across the United States.

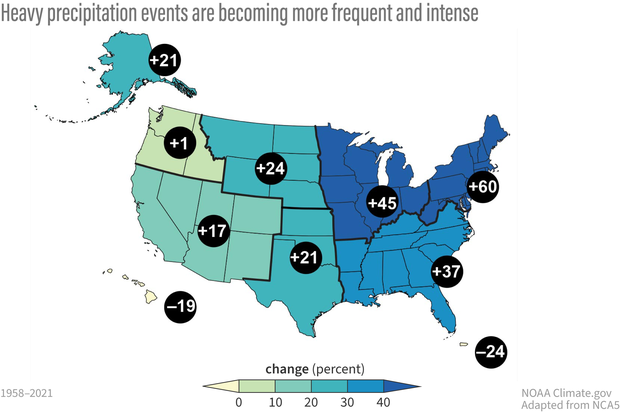

The frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have increased across much of the United States, particularly the eastern part of the continental US, with implications for flood risk and infrastructure planning. Maps show observed changes in three measures of extreme precipitation: (a) total precipitation falling on the heaviest 1% of days from 1958–2021. Numbers in black circles depict percent changes at the regional level. Data were not available for the US-Affiliated Pacific Islands and the US Virgin Islands. Image adapted from original in the Fifth National Climate Assessment.

We have seen record numbers of billion-dollar disasters bringing significant impacts on physical and mental health among affected communities. These increases are linked to population growth and development, but they are also connected to climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) identifies the influence of human-caused climate change on observed ”weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe.” A greenhouse gas-warmed atmosphere is a “thirstier” atmosphere, with a greater capacity to hold more water vapor, creating conditions primed for intensified hurricanes, heavier rainfall, and more flooding. For example, preliminary analysis of Hurricanes Helene and Milton indicate that global warming increased their intensity and rainfall totals and made similar storms more likely than they would otherwise have been.

On average, for every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) the atmosphere warms, it can hold 7 percent more water vapor. When atmospheric processes do trigger rain, that extra "background" water vapor can make it rain more heavily, leading to increased flooding. NOAA Climate.gov illustration.

And we’re seeing surges in emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths with increasingly frequent and severe extreme heat events, as a result of more health-threatening temperature days annually, made more likely by human-caused climate change. One of the hottest areas in the US, in Phoenix and Maricopa County, has seen heat related deaths quadruple in the last 5 years.

Research shows that those who tend to be hurt first and worst are children, older adults, those with chronic diseases, and people of color living in under-resourced communities. While this type of climate science and health content was not always part of medical education, we see growing efforts to remedy the gap. For example, Dr. Gaurab Basu and medical student partners at Harvard Medical School have implemented a trail-blazing curriculum to prepare medical students and doctors to face climate-related challenges.

An elderly woman faints from heat on New York City's Upper East Side in 2011. Photo from New York Daily News/Marcus Santos.

3. Educating the public and engaging communities

Clinicians can educate patients on their increasing exposure to climate-driven hazards; and then help them connect the dots on why their symptoms for existing conditions, like allergies and asthma, could worsen, and what they can do to protect themselves and their families. I find hope in prevention and proactive wellness management, just as I did while in the throes of the COVID pandemic.

I am inspired by the growing community of climate doctors who are mobilizing to heal our communities and our ailing planet. For example, one of my colleagues is sharing public health messaging on how “plant-forward diets” (an approach to eating that centers fruits, vegetables, legumes and grains but is flexible to include smaller amounts of dairy, meats and seafood) simultaneously keep our brains and bodies healthier and help slow global warming. There’s a win-win!

Another colleague is working to protect and improve our youth’s mental health through engaging them in ecosystem restoration efforts. Getting youth outside and involved in restoration projects protects the environment, helps them learn more about nature and gives them a sense of purpose and empowerment that, research shows, helps mitigate feelings of anxiety and depression. That’s a win-win-win!

4. Advocating for policy and systems change

As trusted science professionals, physicians can lend their expertise beyond the clinic and community health, and step into the realm of health systems and policy work. Physicians and other health professionals have aligned efforts in organizations like Health Care Without Harm and Practice Greenhealth to reduce the greenhouse gas pollution created by the health sector. For example, anesthesiologists are advocating to eliminate leaky and wasteful anesthetic gas systems and choose better agents for anesthesia that work just as well for patients but aren’t as harmful to our environment. A growing number of health organizations have signed the HHS Health Sector Climate Pledge to reduce emissions of heat-trapping gases by 50% by 2030, and net zero by 2050; and to develop plans for making clinics and hospitals and the communities they serve more climate resilient. Groups of physicians and health professionals can advocate for this type of commitment from their employers.

A path to healing

A few short years ago, I couldn’t see how to affect change in the face of the climate crisis as a family physician. Now, I see networks of health professionals working to combat the climate crisis and protect our communities. From the exam room to the classroom, climate doctors are treating patients, educating the public, and advocating for change with system leaders. To quote essayist and climate activist Rebecca Solnit, “Hope is not a lottery ticket you can sit on the sofa and clutch, feeling lucky. It is an ax you break down doors with in an emergency.” Through climate medicine, I have leaned in, learned, found solutions, and joined a movement for collective action. I have an ax in one hand to break out of this emergency, and a handful of seeds in the other hand to plant a new future for our loved ones and families to thrive.

Anne Getzin, M.D., has started thinking of herself as a "climate doctor," who can help her patients and community prepare for the impacts of climate change on human health. Photo courtesy Anne Getzin.

My heart is full of hope as I serve my community, my home planet, and my daughters by fighting for this purpose every day. I call on everyone reading this to take a moment to reflect on the roles you play in your family, your community, and your profession—how are they connected to the health and wellbeing of the rest of the world? What win-win strategies can you envision that align with your values, promote better health and wellbeing, and help address our collective climate crisis? What is your path to find hope? I am profoundly grateful to have found mine in becoming a climate doctor.