For NOAA scientist and Bronx native Shae Green, getting a PhD in marine biology depended on finding the right mentors at the right time

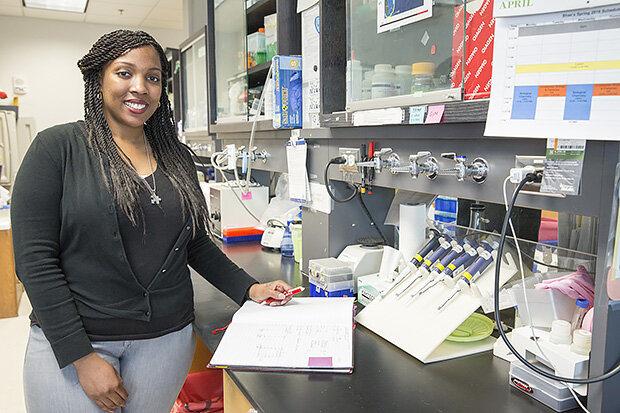

Shadaesha Green describes her research on deep-sea crabs. Credit: University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

In summer 2013, before her senior year at Hampton University, Shadaesha “Shae” Green worked as an intern for marine scientist J. Sook Chung in her lab in Baltimore at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Sciences- Institute of Marine & Environmental Technology (UMCES-IMET). Shae was assisting Chung in her study of the reproductive biology of the snow crab and the red deep-sea crab when her boss brought out some boxes from the lab freezer.

“These four boxes are your PhD,” said Chung. In the boxes were collection tubes filled with RNAlater, a preservative for crab tissue samples.

Shae balked. She was shy and introverted and didn’t have the right temperament for a PhD, she said. The scale of the PhD process overwhelmed her. At most, she planned to pursue a master’s degree. Chung continued to insist. She had funding available for a PhD student to support her work in the lab and join research cruises. Shae’s advisor at Hampton, marine biologist Deidre Gibson, also pushed Shae to change her mind. At this time, there was no one in Shae’s social and professional network who could coach her on what a PhD meant besides Gibson, and they spoke often.

Ultimately, Shae relented. She appreciated Gibson’s patience in answering her questions one by one and providing reassurance. Gibson helped Shae add courses necessary to qualify for the PhD program, and Shae began her PhD in fall 2014. She fell in love with her advanced study in marine biology under Chung. In spring 2022, she completed her studies, defended her thesis, and earned her PhD.

A Bronx childhood

Before college, Shae rarely ventured outside the borders of the Bronx, one of New York City’s five boroughs. If the Bronx were a city of its own, it would rank as one of the largest in the United States, at well over one million residents. The history and culture contained in those 42 square miles inspire many residents with borough pride. The borough is home to the Yankees baseball team and the Bronx Zoo. Neil deGrasse Tyson, the eminent physicist and science communicator, grew up in the area and attended The Bronx High School of Science. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor also grew up in the borough. The Bronx is home to the historic Woodlawn Cemetery, the final resting place of jazz virtuosos Miles Davis and Duke Ellington, songwriter Irving Berlin, newspaper owner Joseph Pulitzer, writer Herman Melville, and women’s suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

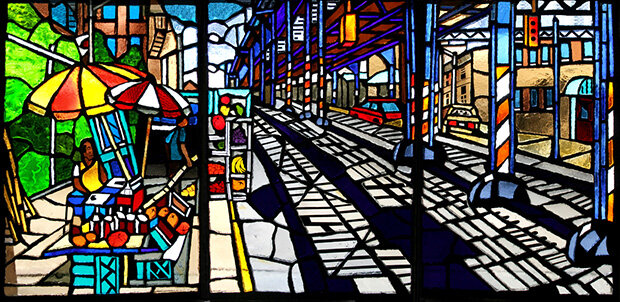

Daniel Hauben, an artist born and raised in the Bronx, depicts common borough sights: a mango vendor by an elevated railway. Mango Vendor by Daniel Hauben. Published with permission of the artist.

Shae remembers well the sights and sounds of the Bronx in the 1990s and 2000s, when the borough was growing in population and economic power. She recalls the music of nightlife coming through her room window. The Bx36 bus, the 2 and 5 elevated trains, and the car horns. She recalls the neighborhood bodegas—a corner grocery and convenience store unique to New York City. The bodegas offer breakfast sandwiches, snacks, household supplies, and a “chop cheese”—a deconstructed cheeseburger. Usually, a bodega has a cat or two inside or sitting on the ice chest outside. A bodega is incomplete without a cat.

As a child, Shae often visited Crotona Park, the largest park in the South Bronx. At Crotona, she would visit Indian Lake, a 3.3-acre lake with ducks, turtles, and fish. Crotona and other parks have long featured a big community summer barbecue called “Old Timers Day,” a favorite event of Shae’s. “If the park we were in had a swing set, us kids would migrate to it,” said Shae. “Or over to the yelling ‘Coco, Mango, Cherry’ guy and the ‘Icy lady’ who push their carts through parks and neighborhoods selling flavored ice snacks for $0.50 to $1.50.”

Going to college

In high school, Shae excelled academically. She joined the National Honor Society and did extracurricular activities like senior center volunteer work and scrabble club. But she did not think much about leaving the familiarity of the Bronx. No one in her family had attended college, and few graduates of her high school, University Heights, considered 4-year colleges. Most students could not afford college. About eighty-six percent of Shae’s class graduated in four years.

University Heights, moreover, lacked some of the critical foundations for college preparation. During Shae’s secondary school career, University Heights did not have an Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate program. The school’s student-to-teacher ratio was high. Today, according to U.S. News and World Report, the school’s student-to-teacher ratio is 20:1. Just three percent of the student body passed at least one Advanced Placement exam in 2021. Based on student performance on state-required tests and internationally available exams on college-level coursework, U.S. News and World Report gave University Heights a College Readiness Index of 12.7 out of 100. Most University Heights students qualify for the federal free or reduced-price lunch program, a sign the surrounding communities are struggling economically.

Despite these headwinds, Shae’s mentors pushed her to take risks and pursue self-enrichment and discovery. During her junior year, her father gave her a pamphlet for a people-to-people student ambassador program which took students on international summer tours. Knowing she would be reluctant to apply, her dad put in her application, and they went together to secure her first passport. “Looking back, I was really stubborn,” said Shae. That summer—her first big adventure--took her to Sicily, Malta, and Paris.

Shae in the early 2000s, attending University Heights High School in the Bronx. She is with her high school guidance counselor, Lillian Martinez. Photo credit: Shae Green.

When senior year arrived, Shae considered going to city college or staying at home. She thought about becoming a teacher. She cruised on this path until her chemistry teacher, Cynthia Loran, approached her with a college brochure with a list of majors and asked Shae to pick one. She chose environmental science because it seemed to her to be the science with the least biology. At the time, she disliked classroom biology because it was abstract rather than hands-on, and it required so much memorization. With Cynthia’s encouragement, Shae selected environmental science as her major and began applying to colleges with relevant programs.

Her math teacher, Erick Jenkins, wanted more of his students to apply to historically Black colleges and universities, like his alma mater, Hampton University. He encouraged Shae and her peers to use the common Black college application to apply to over sixty of these schools, which were founded before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made college segregation illegal. Also, her mother pushed her to attend a Hampton University “on-site admission day” event. Shae agreed to go to the event, and Hampton accepted her application on the spot. While visiting Hampton University for its annual High School Day in April, she was impressed by the school’s marine environmental science program on the waterfront, near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. She committed to the school. After overcoming some initial culture shock, she fell in love with Hampton.

Mentorship at Hampton University

After her freshman year, Shae sat down with her advisor, marine biologist Deirdre Gibson, an experienced, award-winning professor and mentor at Hampton. Gibson said Shae’s performance academically was “OK, but could be better.” Gibson invited Shae to work in her lab, where Shae counted and identified phytoplankton for her a few hours after class. She also learned how to preserve biological samples and operate the microscope.

Gibson introduced Shae to Hampton’s partnership with the NOAA Living Marine Resources Cooperative Science Center, which opened doors for her. The center trains students from underrepresented communities in marine science for careers in research, management, and public policy that support the sustainable harvest and conservation of the nation’s living marine resources. Through the center, Shae received a stipend for working in Gibson’s lab, completed science internships during the summers after her sophomore, junior, and senior years, and attended her first scientific conferences.

Gibson challenged Shae to continue to grow emotionally and intellectually. With this support, and her own intrinsic curiosity, Shae immersed herself in the world of marine biology and built an identity as a scientist. Her hands-on summer internships transformed the way she thought about biology. It became her passion.

As she grew, she found new ways to give back to the community. For example, junior year, she volunteered to help at a student-led community health fair in an underserved area of the city of Newport News. Dentists, doctors, and other health care professionals at the fair offered free checkups for children. “That was the first time I saw that doing outreach could make a difference in someone’s life,” said Shae.

Through a summer internship, Shae met an important new mentor, marine scientist J. Sook Chung, her future PhD advisor. “It was great, I loved meeting her,” said Shae. “Her mind—she always has questions. Her mind works really fast. She moves really fast because of that. Something is always on her mind. She walked down the hallway so fast and it was hard to keep up!” Having such mentors helped Shae excel academically. She obtained her bachelor’s degree in marine and environmental science at Hampton and then received the two-year Louis Stokes Alliance Minority Program (LSAMP) Bridge-to-Doctorate Fellowship Award and a graduate scholarship from the NOAA Living Marine Resources Cooperative Science Center to support her PhD.

Shae working on her PhD at University of Maryland Center for Environmental Sciences-Institute of Marine & Environmental Technology. Photo credit: Shae Green.

Completing her PhD

As a PhD student, Shae focused on hormone biology in red deep-sea crabs. “Right now,” she said, “the red crab is a federally managed species, but there’s little known information about their biology, so we don’t know a lot about their reproduction and molting patterns. Looking at these hormones and studying their effects on reproduction is important so we can have an insight into the patterns of the hormones regulating ovarian development. Then we can take what we learn to provide additional life history information that can be used by researchers and federal managers, such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, that set regulations, including catch size.”

Summer 2014, Shae joined a fishing expedition aboard the vessel Hannah Boden. She sampled red deep-sea crabs. Photo credit: Shae Green.

Shae worked hard on improving her science communication skills. At the American Fisheries Society conference in 2019, Shae was paired with NOAA fish biologist Shivonne Nesbit as a mentor. Nesbit told her, “Before the end of this conference, I want you to meet three new people, by yourself.” Shae called it “the most intimidating thing I had done.” As an undergraduate, she had avoided public speaking roles at conferences. Instead, she resorted to lower-profile poster sessions, where she would stand in front of her poster and take questions from passersby. With encouragement and insistence from Nesbit, Chung, and others, however, Shae met the challenge of public speaking as a PhD student. Conference after conference, she slowly acquired fluency with networking and major speaking roles. Shae also applied for and won a 2021-2022 Knauss Fellowship at NOAA Sea Grant, which placed her at the NOAA Climate Program Office for a year. During her Fellowship, she concentrated on building her knowledge and skill in science communication. She contributed communications support to the Climate Risk Areas Initiative, on issues ranging from marine ecosystems to coastal inundation.

From January 2021 to January 2022, Shae completed a Knauss Fellowship at the NOAA Climate Program Office's Communication, Education, and Engagement Division. Photo credit: Shae Green.

Aware of the impact that mentorship has had on her career, Shae found time between raising her child and completing her PhD to reach out to the community through science education. Three times, she volunteered to speak to students for STEM week at Franklin Square Middle School in Baltimore. Each outreach event goes a little more smoothly for her, as she learns how to better distill complex science into physical, relatable activities. “If they’re hands-on, and they’re doing something, then they’re actually listening to me,” she said.

On three occasions, Shae also volunteered for Institute of Marine & Environmental Technology’s annual Open Day, an open house for children and families to learn about the mission of the institution in the community, which is to develop innovative approaches to protect and restore coastal marine systems and their watersheds, sustainably use resources in ways to benefit human well-being, and to integrate research excellence with education, training, and economic development. She prepared an activity for children which had worked in the past. She wore a crab eyes hat to catch their attention and kick off a discussion about the importance of crabs’ eyes to their hormone system.

“That was more geared toward the little ones,” explained Shae. “It was really nice because I would do the crab eyes and you’d see them walking around Open Day with the crab hats on. That was really cute. It helped them to get a little information but the more interesting part was that the parents were getting it. The parents, because of the blue crab in the Maryland area, the parents were really interested in what I had to say about crab eyes and why they’re important. That was pretty cool. I was aiming to get the little ones to understand but when I saw that the parents were really understanding, I was happy.”

Mentorship at NOAA and beyond

She recently accepted a new job at the NOAA Office of Education, where she works as a program specialist on the Environmental Literary Program, which provides grants and in-kind support for programs that educate and inspire people to use Earth system science to improve ecosystem stewardship and increase resilience to environmental hazards. She applies her deep experience with mentorship and scholarships to help the cause of NOAA science education. “I have a responsibility to give what I’ve received as far as the mentorship that I’ve had. Even if it’s one person. To show someone that there is more out there than they realize.”

Shae draws from her experiences with J. Sook Chung and Deidre Gibson to find templates for future science mentorship. With Chung, she said, “It’s nice that there’s that science mentorship and that personal connection, too. Being able to talk through problems with her. That’s really nice.” Shae said that “perseverance” is the keyword for effective mentorship.

Shae still visits the Bronx and lists the changes in her old neighborhood she has observed over the years. One of her favorite recent outreach events took her back to University Heights High School. Her virtual audience of sophomores and juniors wanted to know how it was leaving the Bronx. They wanted to know how it was being away from home for the first time. What it was like coming home to the Bronx after being at college for a long time. “A lot of the girls, I remember, for sure, appreciated me telling my story,” said Shae. “Because they are looking into colleges but had questions about how I handled finances and going too far from home. It felt good to talk to my high school. They are very proud of where I am. And without my teachers there thinking of me, I would not be where I am today.”

“Now, going forward,” she added, “it’s important to say I’m from the Bronx. For the generations that are still there, it’s important to say: I came from this place.”

References

2020–21 School Performance Dashboard. NYC Department of Education. Accessed April 26, 2022.

Author interviews with Shae Green, August 20, 2021; September 1, 2021; and September 29, 2021

A Walk through Bronx: History. Thirteen. Accessed April 26, 2022.

The Bronx High School of Science. Accessed April 26, 2022.

Chan, S. (2008, August 13). A Bronx Artist’s Ode to Street Life, in Glass The New York Times. Accessed April 26, 2022.

Cheney, J. (2021, November 14). 10 Historic Graves to Visit in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Uncovering New York. Accessed April 26, 2022.

Crotona Park Amphitheater. Facebook. Accessed April 26, 2022.

Hill, J. (2009, June 30). Neil deGrasse Tyson, Astrophysicist. Gothamist (Wayback Machine) Accessed April 26, 2022.

Old Timer Day Bronx NY. Monsterphoto Blog. Accessed April 26, 2022.

Opie & Anthony: Neil deGrasse Tyson ft. Rich Vos & Bob Kelly. YouTube. Accessed April 26, 2022.

University Heights Secondary School-Bronx Community College. U.S. News & World Report. Accessed April 26, 2022.

Wirsing, R. (2019, August 27). Old Timers Day Music Fest At Crotona Park. Bronx Times. Accessed April 26, 2022.