As the North Slope of Alaska warms, greenhouse gases have nowhere to go but up

The amount of carbon dioxide being released from tundra in the northern region of Alaska during early winter has increased 70 percent since 1975, according to a new regional climate paper by scientists participating in a research project funded by NOAA and NASA.

NOAA’s Barrow Atmospheric Baseline Observatory sits on the northernmost point of land in the U.S, just outside the town of Utqiaġvik (Barrow in English). NOAA photo.

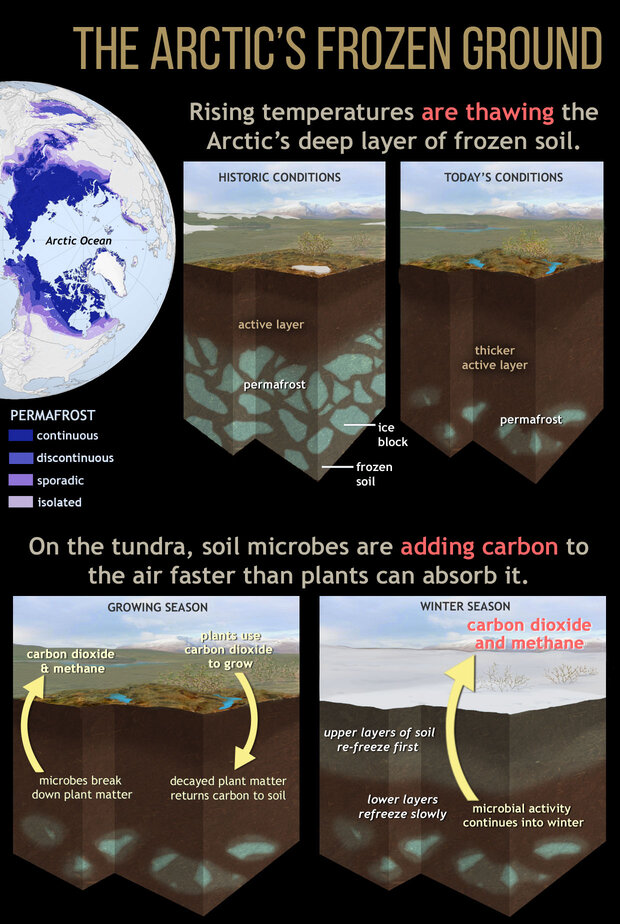

The fate of carbon locked in northern permafrost—vast regions of frozen soil containing undecayed vegetation—is of intense interest to scientists. That’s because these soils contain an estimated 1,330-1,580 billion tons of organic carbon, about twice as much as currently contained in the atmosphere.

When permafrost thaws, carbon can be released to the atmosphere either as methane or carbon dioxide (CO2). Scientists are concerned that increasing greenhouse gas emissions will accelerate a regional warming trend that could drive a further increase in greenhouse gas emissions from the tundra.

Permafrost is like a giant freezer for carbon: thousands of years worth of plant, animal, and microbe remains mixed with blocks of ice. Historically, only a shallow "active layer" thawed in the short summer. In today's warming Arctic, permafrost is thawing, and the active layer is getting deeper. Warming in the growing season has increased plant growth and allowed plants to remove more carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air during photosynthesis, but decomposition of organic matter by soil microbes is also releasing carbon dioxide and methane. In the past decade, the parts of the Arctic tundra that are routinely observed have become a net source of carbon-containing greenhouse gases because microbial activity is continuing well into winter after plants go dormant. NOAA Climate.gov drawing. Permafrost map from NSIDC.

Climate models used in recent climate assessments do not show the early winter carbon release in this region or in other northern tundra regions in the Arctic.

Warmer fall temperatures observed in northern Alaska delay freezing of tundra, increasing the length of time the tundra is giving off greenhouse gas emissions during the year, according to the study’s lead author Róisín Commane of Harvard University.

“In the past, tundra soils may have taken a month or so to freeze, but with warmer temperatures in recent years there are locations in Alaska where tundra soils now take more than three months to freeze completely,” said Commane. “We are seeing emissions of carbon dioxide from soils continue all the way through this early winter period."

Results of the study were published in last month’s Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

NOAA Barrow observatory’s long-term data is key

The new study measured CO2 emissions above Alaska by instrumented aircraft from April through November in 2012, 2013 and 2014 as part of the Carbon in Arctic Reservoirs Vulnerability Experiment (CARVE). The long-term change in regional emissions on the North Slope was estimated by analyzing NOAA’s 41-year record of CO2 measured at NOAA’s Barrow Atmospheric Baseline Observatory.

Long-term trends in monthly average carbon dioxide (pink line, left vertical axis) and methane (green line, right vertical axis) concentrations at NOAA's observatory on the tundra in Barrow, Alaska. NOAA Climate.gov graph of in situ data, adapted from originals created by the data visualization tool on the NOAA Earth System Research Lab's website.

Barrow was also chosen because it has been warming about twice as fast as the rest of the North Slope, and offers a potential preview of how other northern tundra regions could respond to increased warming in the future, according to study co-author Colm Sweeney.

In 2016, Sweeney, a CIRES scientist working at NOAA, published research analyzing NOAA’s Barrow database and found the thawing permafrost was not releasing large amounts of carbon as methane, as some scientists had predicted.

“It wasn’t showing up as methane,” Sweeney said. “It is showing up as carbon dioxide.

“This new research demonstrates the critical importance of long-term monitoring to identify feedback mechanisms, which may amplify the unprecedented warming we are seeing throughout the Arctic,” he added.

Commane, Sweeney and their colleagues are extending their research on Arctic carbon dioxide with the new NASA's Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE) project, which is in the second of five field seasons in Alaska and northwest Canada.

For more information, please contact Theo Stein, NOAA Communications, at 303-497-6299 or theo.stein@noaa.gov. This story was originally published on NOAA's OAR website. It has been re-used with permission.