Women’s History Month: early women in Earth and climate science

For Women’s History Month, Climate.gov has decided to take a brief look at some of the early women in earth and climate science. Women’s History Month serves to honor the first women who had the courage to break into traditionally male spaces and to acknowledge those who went unrecognized for their contributions. It’s likely all of these women faced significant gender discrimination but persevered in the name of discovery. In many cases, their achievements are still not given the recognition they deserve. Below is an incomplete timeline of women in earth and climate science history over the past two centuries.

1800s

Etheldred Benett (1776-1845)

Etheldred Benett is often credited as being the “First Female Geologist.” Independently wealthy and never married, Benett was an expert on fossils and stratigraphy in southwest England. She published books on her collection, supplied fossils to museums, and served as a reference for other geologists of her time. Because of her unusual first name, Benett was mistakenly granted a Doctorate of Civil Law from the University of St. Petersburg at a time when women were not admitted into higher education institutions.

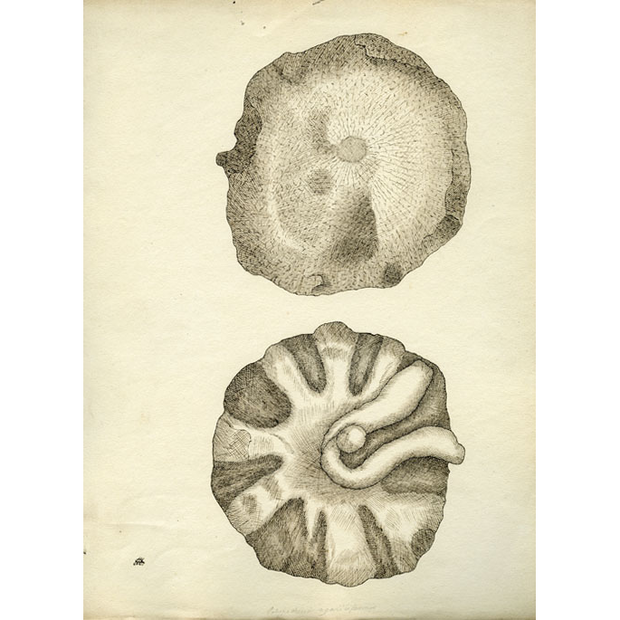

A sketch drawn by Etheldred Benett of a fossil sponge in her collection. Some fossils in her collection were the first to be illustrated and described; others were extremely rare or very well preserved. (The Geological Society)

Mary Anning (1799-1847)

Mary Anning, a paleontologist and fossil collector, was the first to discover a complete skeleton of a Plesiosaurus. (The Geological Society of London convened a special meeting to discuss whether the fossil was a fake; Anning was not invited.) As a child, she assisted her father with his fossil collection. Despite her reputation for finding and identifying fossils, the men who dominated the scientific community often did not acknowledge her work. Today, the Natural History Museum in London showcases several of Mary Anning’s finds.

Portrait of Mary Anning with her dog, Tray, and the Golden Cap outcrop in the background (Natural History Museum, London). This painting was owned by her brother Joseph, and presented to the museum in 1935 by Miss Annette Anning.

Eliza Gordon-Cumming (1795-1842)

Eliza Gordon-Cumming was a paleontologist and illustrator whose illustrations gained the attention of major fossil collectors. Her illustrations were so helpful that a paleontologist named a fossil fish for her (Cheirolepis cummingae). She began collecting fossils from the quarry on her husband’s estate. Her finds appeared in Louis Agassiz’s 1844 Monograph on Fossil Fish of the Old Red Sandstone. Her fossils are still regarded as important specimens, held in collections all around the world.

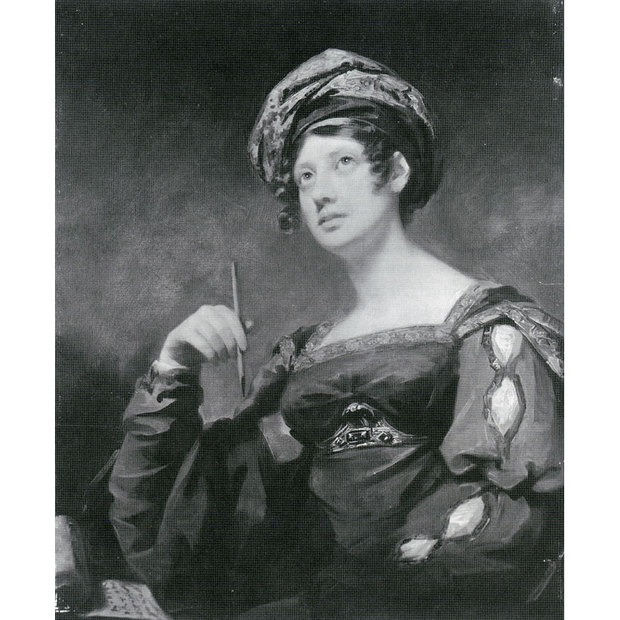

Eliza Mary Campbell, Lady Gordon-Cumming, in a portrait by Henry Raeburn, between 1815 and 1823. (Northern Scot)

Mary Horner Lyell (1808-1873)

Mary Horner Lyell often traveled with her husband as his partner in geology. While Charles investigated, she sketched geologic structures and cross-sections they discovered. Mary helped her husband research and catalog the rocks, minerals, and fossils they collected. Charles Lyell was an internationally recognized geologist, but couldn’t communicate with French, German, Spanish, or Swedish geologists without help from his wife. She acted as his interpreter with European geologists, as her fluency in four other languages allowed her to translate letters. Horner Lyell attended her husband’s talks as well as special lectures at the London Geological Society.

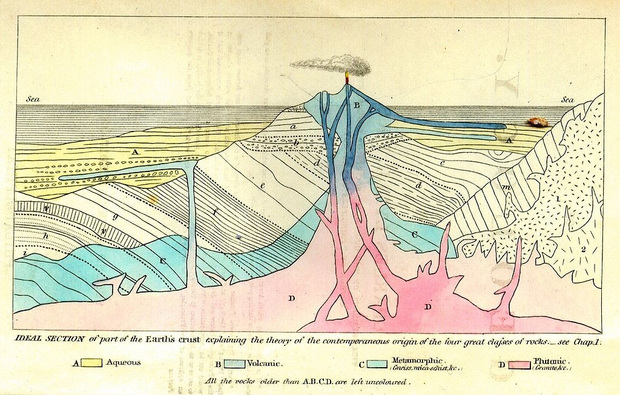

A drawing of a portion of the Earth’s crust by Horner Lyell. (Trowelblazers)

Florence Bascom (1862-1945)

While studying for her PhD at Johns Hopkins University, Bascom was forced to sit behind a screen in the corner of the classroom so as to not disturb her male classmates. This made it hard for her to hear or see the lectures. After graduating, she became the second woman to earn her PhD in geology in the United States, after Mary Emilie Holmes. In 1896, she became the first woman to work for the United States Geological Survey. She spent her summers doing fieldwork, analyzing her samples, and preparing maps during the academic year while teaching as a professor in the geology program she created at Bryn Mawr College. Her best known work is her study of the Piedmont region of Maryland and Pennsylvania.

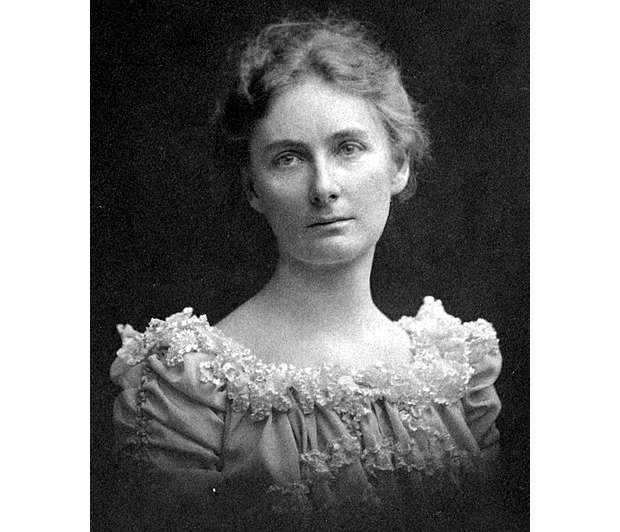

Florence Bascom ca.1900. (USGS)

1900–1950

Alice Wilson (1881-1964)

When Wilson retired at 65, five people had to be brought in to replace her. As a child, she collected fossils with her family and developed an interest in paleontology. While working alone on remote sites for the Geological Survey of Canada, she mapped over 14,000 square kilometers of the Ottawa-St. Lawrence Lowlands. She did this on foot or on a bicycle until she could buy her own car; the GSC would not grant her a vehicle like it did for its male geologists. In addition to her scientific achievements, she wrote a famous children’s book on geology called “The Earth Beneath our Feet.”

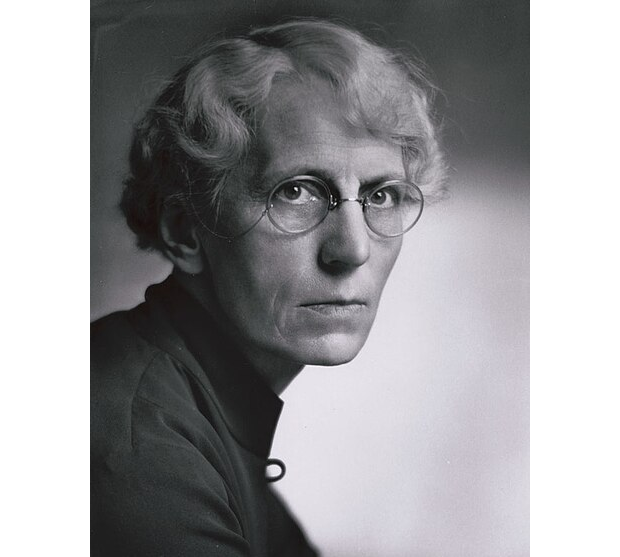

A portrait of pioneering Canadian female geologist Alice Wilson. (Science.ca)

Eileen Guppy (1904-1980)

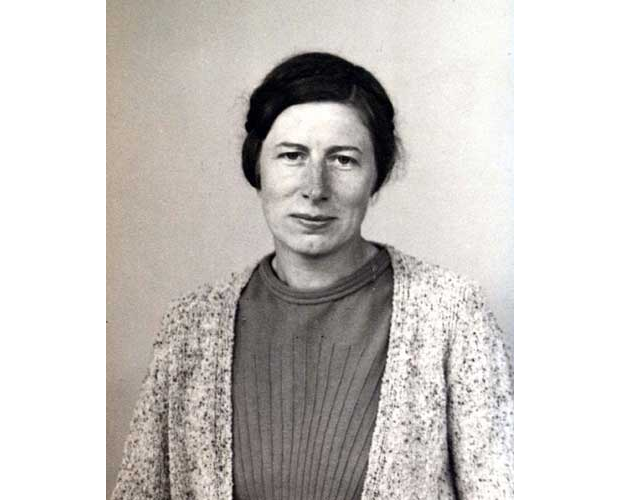

Eileen Guppy was the first female geologist in the British Geological Survey. During World War II, many women worked in roles that had been vacated by men who had been called to fight. Having already worked as a petrologist and analytical chemist for over twenty years, she was finally given the official title and responsibilities of a geologist in 1943. Three years later, Guppy was demoted as men returned to their pre-war roles. Her many contributions to British Geological Survey publications and reports are rarely credited.

Portrait of British geologist Eileen Guppy. (Trowelblazers)

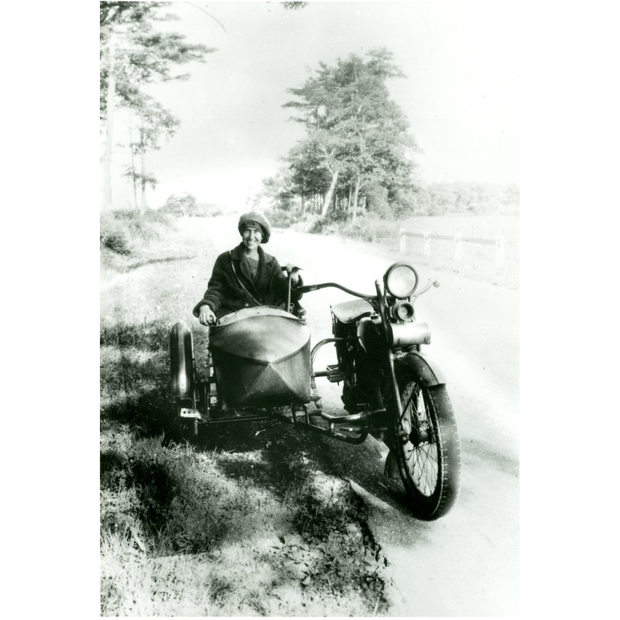

Winifred Goldring (1888-1971)

Winifred Goldring was the first female State Paleontologist in the United States. She served as State Paleontologist of New York from 1939 to 1954. She worked at the New York State Museum for over thirty years and was the museum’s first female curator. She had significant contributions to paleontology, including extensive work on Devonian crinoids in New York, and creating innovative museum exhibits. Goldring also served as president of the Paleontological Society and was vice president of the Geological Society in America in 1950.

Winifred Goldring in a motorbike. (Trowelblazers)

1950–2000

Maria Klenova (1898-1976)

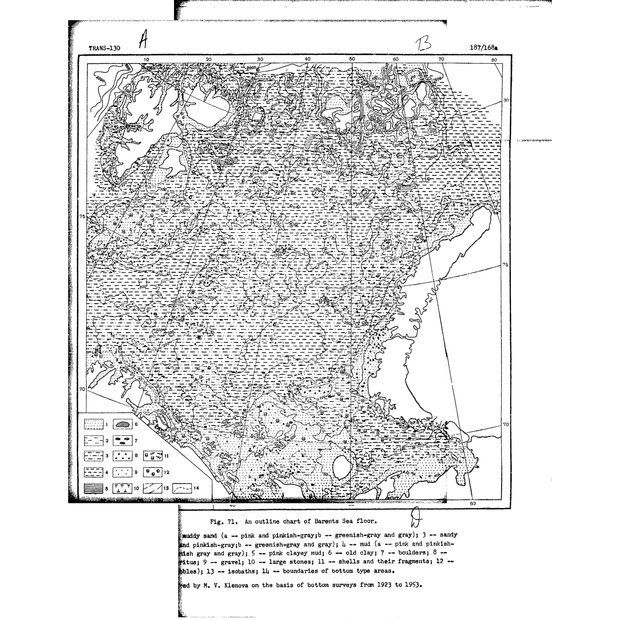

Maria Vasilyevna Klenova was the first female scientist to do research in Antarctica and was a contributor to the first Soviet Antarctic atlas. In 1933, she produced the first complete seabed map of the Barents Sea. During World War II, Klenova was appointed as head of the Laboratory of Marine Geology at the State Oceanographic Institute (GOIN) in the USSR. Her lab produced hundreds of maps that supported Soviet military operations. Several geographic features bear her name, such as Klenova Peak in Antarctica.

A bathymetric map of the Barents Sea. (Klenova 1948)

Moira Dunbar (1918-1999)

Dunbar began her career in sea-ice research working for the Government of Canada after emigrating to Canada in 1947. She took photos of sea ice taken at different times of the year to analyze ice conditions and determine the ice’s predicted position at different times of year. Dunbar also spent nearly 600 hours flying with the Canadian Air Force to study Arctic ice from the air. Dunbar retired in 1978, receiving many prestigious awards throughout her decades-long career.

Moira Dunbar studying Arctic sea ice maps. (Beneath Your Feet)

Katsuko Saruhashi (1920-2007)

Katsuko Saruhashi developed the first method for measuring oceanic carbon dioxide using temperature, chlorinity, and pH, called Saruhashi’s Table. Saruhashi was curious about science from a young age, according to a Massive Science article. After graduating from the Imperial Women’s College of Science, she studied carbon dioxide levels in seawater. Her method became a global standard for measuring carbon dioxide in seawater. She also discovered that the Pacific Ocean releases more carbon that it absorbs, a find that had huge implications regarding climate change. Saruhashi founded the Society of Japanese Women Scientists.

Google doodle of Katsuko Saruhashi. (Newsweek)

Joanne Simpson (1923-2010)

Joanne Simpson was the first woman to receive a PhD in meteorology in the United States. She became interested in clouds as she sailed off the coast of Cape Cod in her youth. Simpson attended the University of Chicago, where Carl-Gustaf Rossby, a famous meteorologist, had recently set up an institute of meteorology. Rossby enrolled her as a teacher-in-training, and she taught meteorology to Aviation Cadets during World War II. After receiving her PhD, she conducted research at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts from 1948 to 1951, then at NOAA from 1964 to 1974. She finished her career at NASA, where her most significant work was as a project scientist for its Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission launched in 1997.

In 1973 Joanne Simpson led the Florida Area Cumulus Experiment (FACE)—a NOAA program to enhance rainfall with cloud seeding. She is shown here aboard a NOAA Research Flight Facility C-130. (Photograph courtesy Fritz Hoelzl, NOAA)

June Bacon-Bercey (1928-2019)

June Bacon-Bercey was the first on-air African-American female meteorologist. She was instrumental in making atmospheric sciences more accessible to minorities and women. In 1954, she became University of California Los Angeles’ first African-American woman to graduate with a degree in meteorology. She then accepted a position as a weather forecaster and analyst with NOAA’s National Weather Service. In 1971, she joined an NBC affiliate news channel as a science reporter. She co-founded the American Meteorological Society’s Board on Women and Minorities, and started a science fair program to encourage students of color and girls to pursue careers in science.

Bacon-Bercey conferring with a colleague at the National Weather Service in 1962. Credit: Dail St. Claire (EOS)

Marie Sanderson (1921-2010)

Sanderson wrote about climate for the general public and published an autobiography, “High Heels in the Tundra: my life as a geographer and climatologist.” While studying geography at the University of Toronto, Sanderson gained an interest in climatology and the polar region. After graduating in 1946, Sanderson wanted to launch a field expedition to the Northwest Territories, the first climate experiment in the region. After defending her dissertation in 1965, she made many trips to the Arctic. These visits inspired her to offer a university course to interested indigenous students in environmental science. She was the first female geography professor in Canada, and the first female president of the Canadian Association of Geographers.

Marie Sanderson wearing her Inuit parka at Inverhuron on Lake Huron, her “favourite place in the world,” in September 2009. (Arctic Institute of North America)

Though many of these women faced significant challenges due to sexism, they were still able to make significant contributions in their respective fields. During Women’s History Month, it’s important to look back on the progress we’ve made regarding gender equality in the sciences, and yet look ahead to the work still to be done. According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES), only one-third of STEM workers are women. The achievements of these inspirational and intelligent women—and others who have yet to receive the recognition they deserve—can inspire today and tomorrow’s women scientists to persevere in the face of adversity.

Works Cited

Acadia National Park. “The Stone Lady, Florence Bascom.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/people/the-stone-lady-florence-bascom.html

Beniest, Anouk. “Maria Vasilyevna Klenova (12 August 1898 – 6 August 1976): The polar scientist who was known as the mother of marine geology.” European Geosciences Union Blog. Dec 21, 2020. https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/ts/2020/12/21/maria-vasilyevna-klenova-12-august-1898-6-august-1976-the-mother-of-marine-geology/

Bogan, Arthur E., and Hugh S. Torrens. 1989. Recovery of the Etheldred Benett Collection of Fossils Mostly from Jurassic-Cretaceous Strata of Wiltshire, England, Analysis of the Taxonomic Nomenclature of Benett (1831), and Notes and Figures of Type Specimens Contained in the Collection. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 141:115-180.

“Etheldred Benett.” Scientific Women. https://scientificwomen.net/women/benett-etheldred-170

Eylott, Marie-Claire. “Mary Anning: The unsung hero of fossil discovery.” Natural History Museum. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/mary-anning-unsung-hero.html

Gibson, Hazel. “Eileen Guppy.” Trowelblazers. May 8, 2014. https://trowelblazers.com/2014/05/08/eileen-guppy-the-first-woman-geologist-in-the-british-geological-survey/

Howarth, Philip. “Marie Sanderson, 1921-2010.” Journal of the Arctic Institute of America 64. March 9 2011. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/arctic/article/view/67138

Hunter, Dana. “Mary-Horner-Lyell: A monument of patience.” Scientific American. April 25, 2013. https://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/rosetta-stones/mary-horner-lyell-a-monument-of-patience/

Klassen, Veronica. “Geoscience Histories: Moira Dunbar.” Beneath your Feet, a Geosciences Blog. Sept. 13, 2022. https://geoscienceinfo.com/geoscience-histories-moira-dunbar/

Mast, Laura. Meet Katsuko Saruhashi, a resilient geochemist who detected nuclear fallout in the Pacific.” Massive Science. March 22, 2019. https://massivesci.com/articles/katsuko-saruhashi-geochemistry-seawater-japan/

Meader, Laura. “Revealing biography of pioneering meteorologist Joanne Simpson an intimate portrayal of triumph over adversity.” Colby News. Oct 7, 2020.

https://news.colby.edu/story/new-biography-of-meteorologist-joanne-simpson/

NASA Earth Observatory. “Joanne Simpson: Discovering the Thrill of Science.” NASA. April 28, 2004. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/Simpson/simpson2.php

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). “Diversity and STEM: Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities.” National Science Foundation. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf23315/report/the-stem-workforce#:~:text=The%20share%20of%20women%20and,(figure%202%2D3).

Snow, Alyssa. “June Bacon-Bercey.” Black Past. Feb 15, 2021. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/people-african-american-history/june-bacon-bercey-1928-2019/

Soldati, Arianna & Freund, Cassie. “Meet Alice Wilson, the Canadian geologist who did the work of five people.” Massive Science. Feb 27, 2020. https://massivesci.com/articles/alice-wilson-geology-paleontology-science-hero/

U.S. Geological Survey. “Florence Bascom, Trailblazer.” USGS. https://www.usgs.gov/news/featured-story/florence-bascom-trailblazer-us-geological-survey

Whitfield, Alistair. “Moray’s pioneering fossil hunter.” The Northern Scot. August 9, 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20230810023620/https://www.northern-scot.co.uk/news/morays-pioneering-fossil-hunter-322708/

“Winifred Goldring.” Museum of the Earth. https://www.museumoftheearth.org/daring-to-dig/bio/goldring

“Winifred Goldring.” The New York State Museum. https://www.nysm.nysed.gov/women-of-science/winifred-goldring