El Niño, East Africa, and Rift Valley Fever

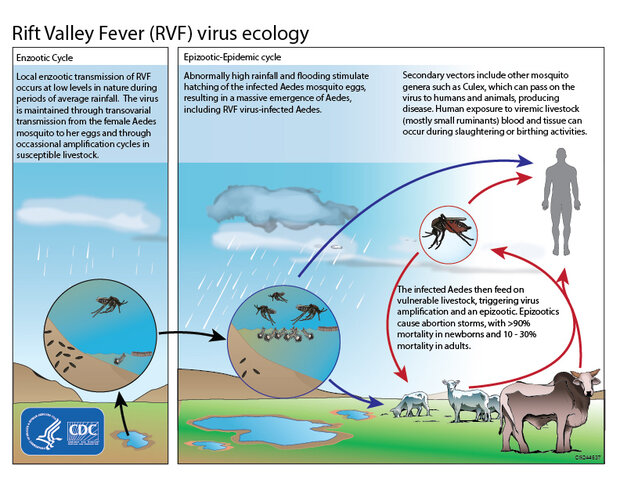

Rift Valley Fever (RVF) is a deadly mosquito-borne disease that affects both humans and valuable livestock in Africa. The fever-causing virus affects the local population and domestic animals such as cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, and camels. Occurring in years of unusually heavy rainfall, the flooding caused by these rains provides an ideal environment for naturally infected mosquito eggs to hatch.

The virus is difficult to control because infected mosquito eggs can survive for years in the normally dry soil. After infection, animals develop high levels of the virus in their blood, thus infecting previously unaffected mosquitoes, which then infect other animals and humans. People can catch RVF either from the bite of a mosquito or through direct contact with the blood, milk, or meat of infected animals, which for many people are a primary source of milk and food.

The ecological cycle of the Rift Valley Fever virus. Credit: Centers for Disease Control.

While most people infected with the virus don’t show any sign of the disease, rarely—about 1 percent of cases—an infected person can develop blindness, swelling of the brain, and hemorrhagic fever. In livestock, the virus is much more serious. Many infected animals, especially the young, die from the disease; almost all infected pregnant animals miscarry.

How do you stop an outbreak?

Once an outbreak in the animal population (known as an epizootic event) occurs, it’s too late to administer action such as livestock vaccines or larval insecticides that kill the infected mosquito population. Humans can try to limit their exposure to the mosquitoes and infected livestock to prevent their own infection, but the livestock mortality rate for infected livestock is more than 90 percent in newborns and 10-30 percent in adult animals.

In 2006-2007, outbreaks in Kenya, Somalia, Tanzania, Sudan, and Madagascar caused more than 200,000 human infections and led to roughly 500 deaths. In Kenya alone, the outbreak cost $32 million in livestock losses and international export bans. An outbreak in 1997 caused 170 hemorrhagic fever-associated deaths and approximately 27,500 infections. The most serious outbreak on record occurred in Kenya in 1950-1951 and resulted in the death of roughly 100,000 sheep.

If it’s not possible to stop an outbreak once it begins, the solution is to try to stop an outbreak before it occurs. With enough warning, health officials can work to prevent RVF illnesses in animals and humans. While there isn’t currently an RVF vaccine for human use, there are vaccines available for livestock. When we know heavy rains are on their way, we can alert health officials, who vaccinate these animals or work to spread pesticides to kill the mosquitos before they hatch.

Vaccinating animals before an outbreak occurs is one of the best ways to prevent RVF's deadly effects. Credit: USAID, Kelley Lynch.

“Early warning of possible Rift Valley Fever outbreaks allows health systems to prepare to diagnose and treat patients, and allows individuals to take steps to reduce infection,” said Cmdr. Jean-Paul Chretien of the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, Defense Health Agency. “Animal vaccination and mosquito control could even prevent major outbreaks, if initiated ahead of time. There is a window of opportunity, but once outbreaks begin, it’s too late for these preventative actions.”

Predicting a possible outbreak

RVF outbreaks in East Africa occur during specific environmental conditions: heavy rains and vegetation overgrowth in areas with low grassland depressions called “dambos.” In an effort to predict when an RVF outbreak could occur, scientists have identified climate patterns that cause these conditions. One such pattern is happening right now: a strong, ongoing El Niño event.

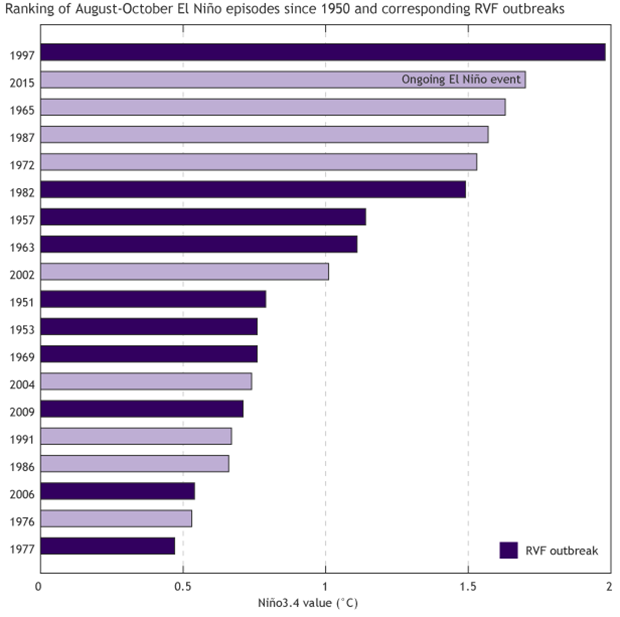

The warm equatorial Pacific waters of El Niño events influence regional weather across the globe. East Africa—which includes Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda, Sudan and South Sudan—have already seen El Niño effects this year. The “short rains” rainy season, which typically runs from October to December, has seen an increase in rain and wetter conditions, making this year potentially ripe for an RVF outbreak.

The current and ongoing El Niño event ranks among the top three El Niños since 1950. In the past, rainfall from strong El Niños have been linked to Rift Valley Fever outbreaks. The above figure ranks August-October average sea surface temperature departures from the mean for all El Niño episodes since 1950. The darker color represents years that have had RVF outbreaks. Figure by Climate.gov, using data from CPC and the USDA.

“Outbreaks can be explosive, but the association with El Niño also creates an opportunity for predicting, mitigating, and even preventing outbreaks,” said Chretien.

To this end, a number of U.S. government agencies work in tandem to monitor the state of sea surface temperature, rainfall, and ecological conditions in order to identify areas at risk of RVF outbreaks. The RVF Monitor website—run by NASA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Defense—developed an RVF outbreak forecasting model. Using satellite-derived data, the model draws on the relationship between RVF activity and El Niño-driven flooding. The RVF Monitor uses El Niño forecast and other data from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

Building the RVF Monitor

The potential to prevent an outbreak with sufficient lead time drove some of the early RVF research at the Department of Defense. During the 1997-1998 El Niño, an interagency program led by NOAA funded work ongoing with the Department of Defense and the Centers for Disease Control to better understand how El Niño might be used to predict RVF outbreaks. This work and these partnerships led to the development of the RVF Monitor, and the opportunity to put that predictive modeling in action.

During the 2006-2007 El Niño event, U.S. government alerts based on these models enabled countries in East Africa to enhance surveillance, communicate risk, and begin preparations two to four months before human infections began. The success of this initiative validated model predictions and led to the RVF Monitor program becoming an operationalized model with monthly updates.

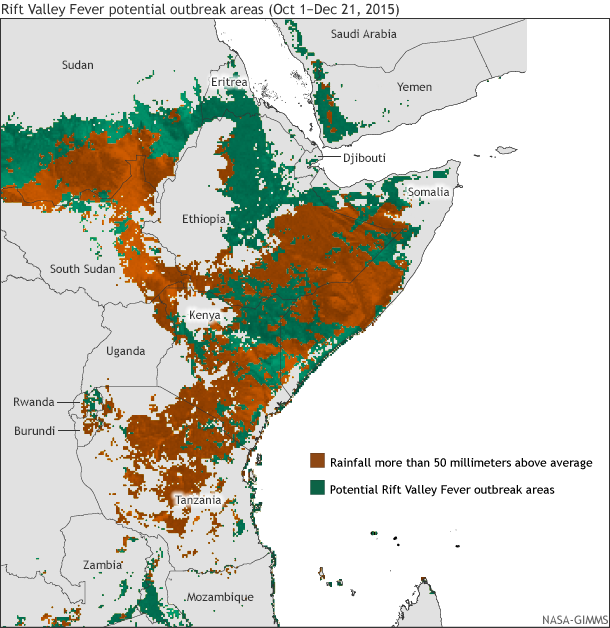

This year, which stands to be one of the top three El Niño events since 1950, the Monitor identified areas at risk for RVF because of the substantially elevated rainfall in Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, and Tanzania. The heavy rainfall in these areas is predicted to continue through early 2016, thus increasing the possibility of an RVF outbreak.

This map shows potential Rift Valley Fever outbreak areas in East Africa. Areas shaded green are locations with previously known or predicted presence of RVF. The areas shaded brown have seen 50mm or more rainfall than average since October 1. Map by Climate.gov, adapted from original by NASA/USDA.

In 2013, the White House established the Pandemic Prediction and Forecasting Science and Technology Working Group. A goal of the group, which comprises experts from across the U.S Government, is to improve warning and prediction for infectious disease threats to human and animal health.

In mid-December, the group released its first pilot-product: an “Emerging Health Risk Notification,” about this year's risk of El Niño-driven RVF outbreaks in East Africa. Their goal is to prevent, or at least reduce, the magnitude of outbreaks affecting human lives, livestock, and trade. By getting these forecasts into the hands of those who need them, the team hopes that humanitarian agencies and health workers can deploy vaccines and mosquito control before the 30-day “window of prevention” closes.

“If we do this right, no one will hear about a Rift Valley Fever outbreak in 2016 because there won’t be one,” said Juli Trtanj, NOAA’s Climate and Health Lead.

More Information

Emerging Health Notification: El Nino and Rift Valley Fever

The Rift Valley Fever Monitor - USDA, DoD, NASA, CDC

Climate Prediction Center: NOAA ENSO forecasts

CDC: Rift Valley Fever Fact Sheet

Sources

ENSO Blog: November El Nino Update - It’s a small world