In 2015, NOAA's Climate Program Office (CPO) invited grant proposals from sea ice and climate scientists looking to better understand and predict Arctic sea ice behavior, on timescales ranging from days to decades. This is our second story on some of the resulting research.

A new crop of studies funded by NOAA's Climate Program Office explores a range of questions about sea ice forecasting, including one of the most basic: how far ahead is it even possible to predict it?

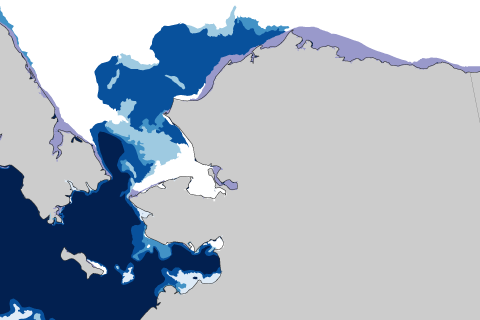

Groundfish stocks in the Eastern Bering Sea are healthy at present, but a recent string of very warm summers, preceded by winters with sparse sea ice, led NOAA biologists to recommend lower catch limits for pollock—the nation's largest commercial fishery.

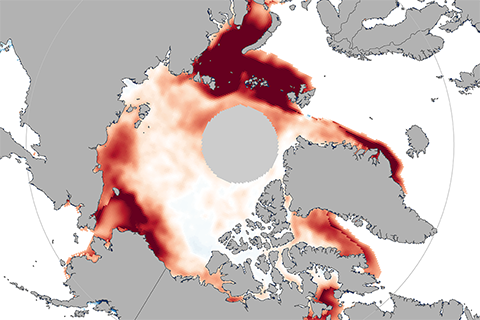

Paleoclimate records show that while there have been several periods over the past 1,450 years when sea ice extents expanded and contracted, the decrease during the modern era is unrivaled.

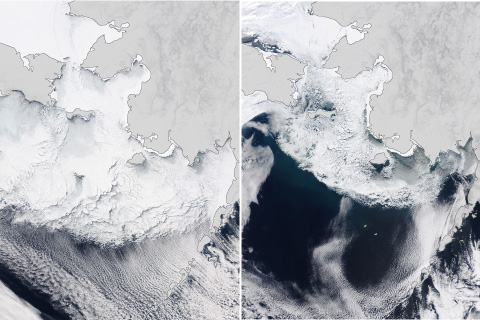

A mild winter and warm spring have led to a large patch of open water in the Chukchi Sea off Alaska, an extremely unusual—possibly unprecedented—occurrence for mid-May.

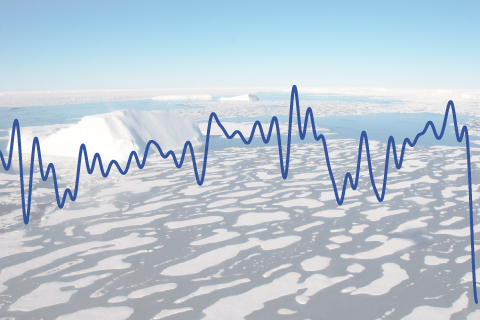

A black swan event is a situation so rare that few people would have imagined it was possible. In November 2016, researchers were caught off guard by just such an event: extremely low sea ice extents in both the Arctic and Antarctic.

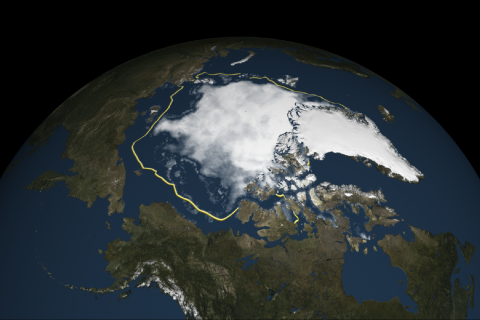

Arctic sea ice ties for second lowest in 2016

September 15, 2016

The 2016 winter maximum sea ice extent in the Arctic edged out 2015 to a set a new record low.

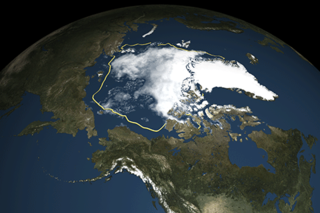

On September 11, 2015, Arctic sea reached its fourth-lowest minimum extent in the satellite record:1.70 million square miles (4.41 million square kilometers).

Since 2002, Octobers in Barrow, Alaska—America's northernmost town—are regularly near the warmest on record, thanks to the retreat of sea ice. The warming hinders traditional hunting activities, makes the town more vulnerable to storm surge flooding, and thaws the frozen ground to greater depths, which destabilizes roads, house foundations, and traditional underground freezers.