March 2018 ENSO update: come on in, the water’s fine

The great La Niña of 2017–18 is dwindling, and forecasters expect the return of neutral conditions by the March–May season, estimated at about 55% likelihood. Neutral conditions are favored to continue through the summer. It’s too early to get a picture of next fall and winter, due to the spring predictability barrier and the absence of strong signs one way or the other. There are a few interesting features we’ll watch closely over the next few months… but first, this update on current conditions!

Stick your toe in

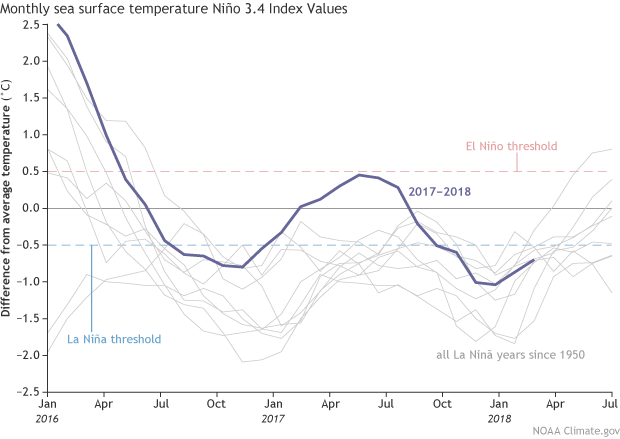

La Niña may be weakening, but she’s still making an impression on the average sea surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific. The Niño3.4 index, which measures the departure of sea surface temperature from the long-term average in the east-central equatorial Pacific, was about -0.7°C during February, using the ERSSTv5 dataset (our most consistent long-term sea surface temperature record.)

Monthly sea surface temperature in the Niño 3.4 region of the tropical Pacific compared to the long-term average for all multi-year La Niñas since 1950, showing how 2016–18 (blue line) compares to other events. Multi-year La Niña events are defined as at least 2 years in a row where the La Niña criteria are met. Both continuous events, when the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) remained below -0.5°C, and years when the ONI warmed mid-year before again cooling, are included here. For three-year events, both years 1-2 and 2-3 are shown. Climate.gov graph based on ERSSTv5 temperature data.

The atmospheric elements of La Niña diminished over February, with the amount of rain and clouds the central Pacific returning to near-normal, and Indonesia actually somewhat drier than average. This is a change from the La Niña-related suppressed rainfall in the central Pacific and greater-than-average rainfall over Indonesia and that was in place over the winter. More evidence that La Niña’s enhanced Walker circulation patterns are fading appeared in the average near-surface winds over the west and central Pacific: these winds were weaker than average during February. (La Niña’s effect is to strengthen the near-surface winds.)

It’s likely that the active Madden-Julian Oscillation that Michelle chronicled last month played into the average February patterns. The MJO is an area of increased storminess that travels eastward along the equator and can circle the planet in about 1-2 months. Near-surface winds tend to blow toward this stormy area, meaning the area behind the MJO experiences more west-to-east wind. When the MJO is moving through the Pacific and into the western hemisphere, as it was during most of February, we can see the average wind patterns in the western and central Pacific become more westerly. Recently, the MJO has weakened substantially.

Making waves

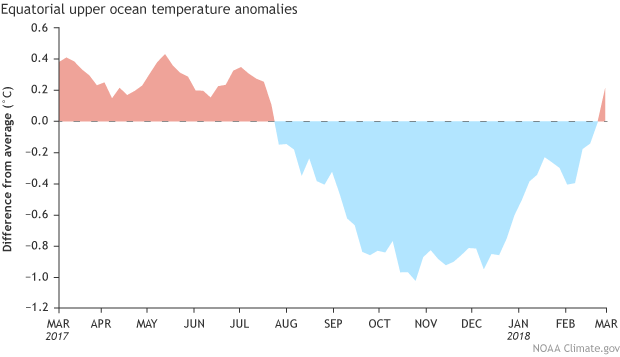

One of the many elements of the Pacific ocean-atmosphere system that ENSO forecasters monitor pretty closely is the temperature of the water below the surface. Colder than the long-term average since August 2017, these waters crept to above normal temperatures in February.

Area-averaged upper-ocean heat content anomaly (°C) in the equatorial Pacific (5°N-5°S, 180º-100ºW). The heat content anomaly is computed as the departure from the 1981-2010 base period pentad (5-day) means. Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

The warming was related to an eastward-moving warmer-than-average blob primarily located between 250 and 50 meters below the surface of the western Pacific Ocean… a downwelling Kelvin wave! As this wave sloshes east under the surface, it will continue to erode the supply of cooler-than-average waters available for La Niña, providing more confidence in the forecast for neutral conditions to develop this spring.

If you feel inclined to examine subsurface temperature anomalies over the past almost-40 years, I’d encourage you to check out my Climate Prediction Center colleague Yan Xue’s great resource for ocean observations.

Pool party

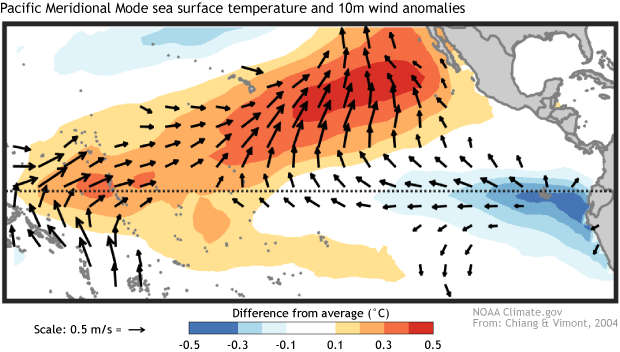

A while ago we were introduced to the Pacific Meridional Mode (PMM for short). In a nutshell, a positive PMM is a pattern of warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures stretching west from Baja California across the Pacific Ocean contrasted with cooler-than-average temperatures along the equator and into the southern hemisphere…

Tropical patterns associated with the positive state of the Pacific Meridional Mode. Red shading indicates above-average sea surface temperature and blue shading indicates below-average sea surface temperature. Vectors show near-surface wind anomalies. Figure based on Chiang and Vimont (2004) and modified by Climate.gov.

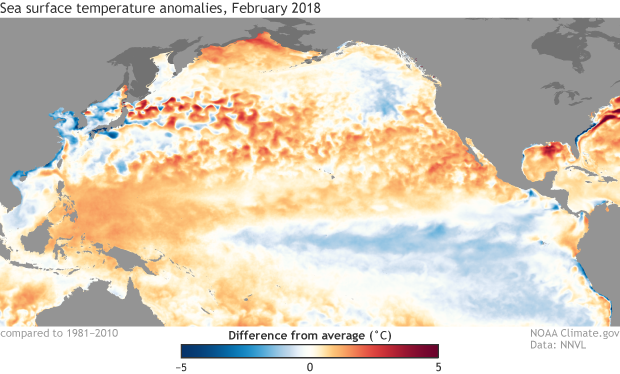

just like the sea surface temperature patterns in the Pacific observed during February.

February 2018 sea surface temperature departure from the 1981-2010 average. Graphic by climate.gov; data from NOAA’s Environmental Visualization Lab.

In fact, the Pacific Meridional Mode index (maintained by our guest blog author Dan Vimont) is the most positive it’s been in years. The contrast between warmer north and cooler south can influence wind patterns along the equator, thereby influencing ENSO. Of course, the global climate system is big and complicated, and it’s too early to say if this strong PMM will be a major factor as the year goes on… but you can bet we’ll be watching it.

If you’d like to compare ocean temperature patterns from this year to the past, you can visit Climate.gov’s Data Snapshots; they also have a nice display of recent temperature and precipitation patterns. Another related resource is NOAA’s Environmental Visualization Lab (select “Add Data” then “climate”). And, of course, here at the blog we’ll keep you posted on all things ENSO.

Comments

Standards for what New England gets

CFS forecasts

Interesting article, I love

Why do you use the 3.4 index

RE: Why do you use the 3.4 index

We have an explainer on our various ENSO indices here:

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/why-are-there-so-many-enso-indexes-instead-just-one

It is not the only region we monitor but we like the Nino-3.4 region b/c it is well correlated with other atmospheric measures of ENSO. It is also one of the few regions of the tropical Pacific that is "Gaussian" which is handy from a statistics point of view (other regions are much more skewed).

ENSO control?

RE: ENSO control?

There is a link between El Nino and carbon dioxide emissions. Mainly El Nino causes less rainfall over Indonesia/Maritime Continent and, along w/ their annual burning, it can increase CO2 emissions. I'm not sure how far back that record goes, but we definitely saw it in 1997-98 and in 2015-16 (two huge El Ninos):

http://www.nature.com/news/massive-el-niño-sent-greenhouse-gas-emissions-soaring-1.22440

Full fledged La Nina at the end of March 2018

RE: Full fledged La Nina at the end of March 2018

We were being tongue in cheek by calling the La Nina of 2017-18 "great." By our standards, it was a weak to moderate La Nina event.

El Nino

Add new comment