A polar vortex double header

A polar vortex double header

“It could be … it might be … it…!” Wait, is it? A homerun for the stratosphere? After a brief respite, the stratospheric polar vortex is expected to weaken again with potentially another major sudden stratospheric warming forecast to occur in the next week. But didn’t we just have a sudden stratospheric warming event?? Read on to find out what’s in the stratosphere’s line-up and how this double header fits in with typical stratosphere behavior.

Loading the atmospheric bases

The atmospheric players have been positioning themselves again for another polar vortex disruption. First up, the current stratospheric conditions are primed for tropospheric wave activity because the polar vortex has been stable and even a bit on the strong side since the end of January. Those strong, but not too strong, west-to-east winds are ideal for atmospheric planetary waves to slide from the troposphere into the stratosphere. This is well-timed as the tropospheric weather patterns, particularly low pressure over the North Pacific and the high pressure over the North Atlantic/Europe, are in a good position to hit amplified wave activity into the stratosphere. Finally, while the stratospheric polar vortex has been strong and stable, it’s likely to start weakening soon as wave activity within the stratosphere itself increases.

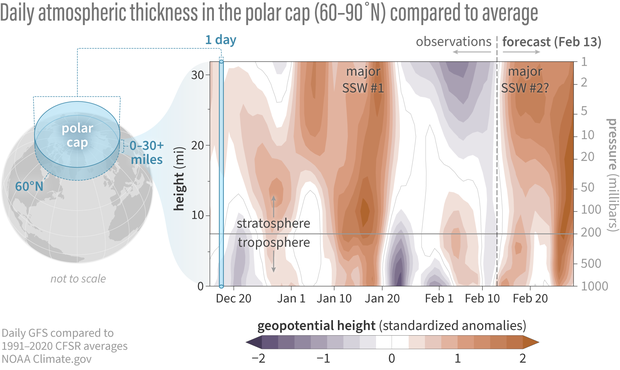

Differences from average atmospheric thickness (standardized geopotential height anomalies) in the column of air over the Arctic from the troposphere to the stratosphere since early December 2023. Since the beginning of February, the troposphere seems to have been uncoupled from the simultaneous conditions directly above in the stratosphere: lower-than-average thickness in the high stratosphere (purple), higher-than-average thickness near the surface (orange). But the recent positive thickness anomalies may be linked to what happened in the stratosphere in mid January. Based on the Global Forecast System (GFS) model, the stratosphere and troposphere are forecast to team up again in the next few days, as the positive height anomalies (orange areas) extend throughout the atmosphere. NOAA Climate.gov image, adapted from original by Laura Ciasto.

Home run or foul ball?

Is the combination of wave activity from both the troposphere and the stratosphere enough to knock the polar vortex out of the park off the pole and weaken the winds? The majority of the forecast models say yes, the winds at 60 degrees North* (the mean location of the polar vortex) will briefly reverse direction within the next week or so, commencing the second major sudden stratospheric warming in as many months. If this second event does occur, it will not be a replay of last month’s game. That major warming event was unique because the disruption started in the lower stratosphere and tore up the vortex from below. This stratospheric warming looks to be more typical, with the wave breaking disrupting the middle stratosphere.

It’s too soon to tell if the disruption will run the bases in the usual way, working its way down to the troposphere. Current forecasts suggest the stratosphere and troposphere will be coupled into the end of February, but the models have been fluctuating from day to day on the degree of coupling, so uncertainty is high. On average, stratosphere-troposphere coupling can occur up to 6 weeks after the warming event, and it can be intermittent because the troposphere has its own processes and weather patterns beyond stratospheric influences. Furthermore, the major warming event may only last a few days, but the polar vortex is forecast to remain weak into March, which can increase the odds of impacting the weather over the next several weeks.

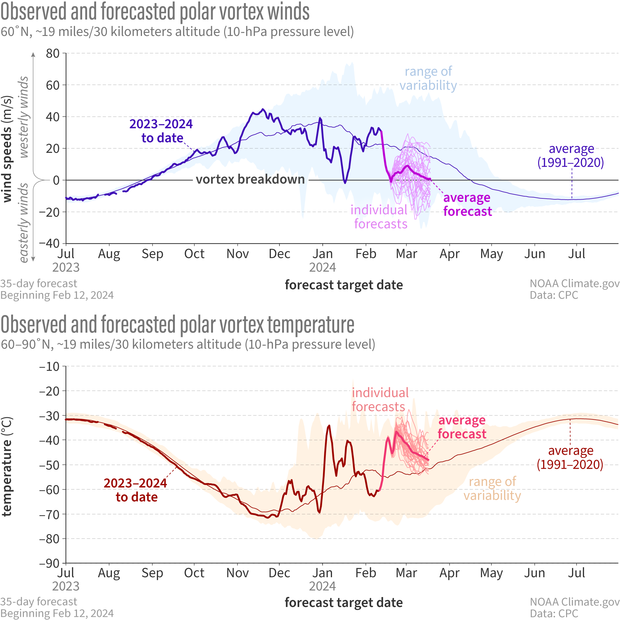

Observed and forecasted (NOAA GEFSv12) wind speed (top) and temperature (bottom) in the polar vortex compared to the natural range of variability (faint shading). For the GEFSv12 forecast issued on February 12, ~90% of the individual model runs predict a reversal of the vortex winds (top, thin magenta lines), accompanied by a sharp increase in stratospheric temperature (thick pink line). While the average of the individual forecasts just crosses the 0 m/s threshold, other forecast models are indicating a larger wind reversal (not shown). If a major warming does occur, it’s currently forecast to last no more than a few days, but the vortex could still remain weaker than normal for the next few weeks. NOAA Climate.gov image, adapted from original by Laura Ciasto.

Batting averages and other stratospheric statistics

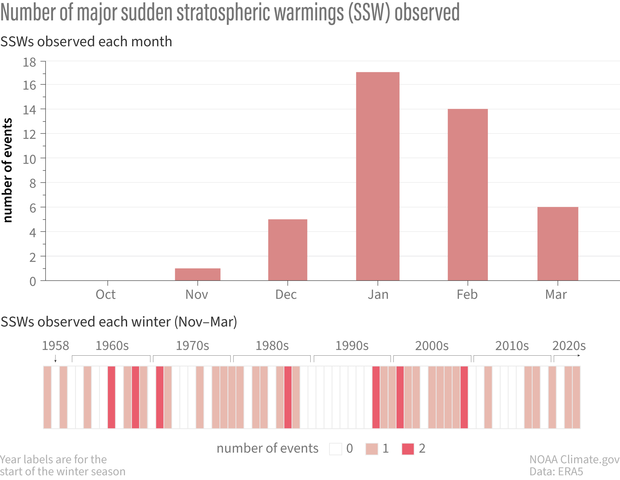

If we were summarize the entire observational record since the 1950s [footnote #1], we’d say major sudden stratospheric warming events typically occur every other year or so. Some years have no major warmings. When they do occur, they’re most common in January or February. What’s less common is having them in both January and February or, for that matter, twice in any winter season.

Frequency of major sudden stratospheric warming events as of a function of (top) winter month and (bottom) winter season (November-March) since 1958. On average, there have been roughly 6 major events per decade since 1958. Some decades have had more than 6 while others have had less. Major sudden stratospheric warmings are most common in January and February. Only one major event has occurred in November. Statistics are based on ERA5 Reanalysis. NOAA Climate.gov image, adapted from original by Laura Ciasto.

Actually, there have been a handful of winter seasons with two major sudden stratospheric warming events [footnote #2]. However in most previous cases, the double major warmings are separated by at least two months whereas this event would only be separated by one month. This may be because the SSW in Jan this year only very briefly reversed the stratospheric winds allowing the polar vortex to recover very quickly.

Almost post game analysis

The season isn’t over yet, but it’s hard not to wonder why this winter has been so active. (Although we’re all pretty sure it was the launch of this blog. We know that you know we’re watching, stratosphere.) It will likely be a good subject for future research. However, there are indications that other climate patterns that influence the polar stratosphere may have been poised to help the stratosphere knock this year out of the park. In a future post, we’ll talk about how these signals, particularly those in the tropics, might impact the stratospheric home runs statistics.

[*Editor's note. Revised on April 26, 2024. This sentence originally said ,"...the polar vortex winds will briefly reverse direction...".] It's been revised to prevent confusion between the polar vortex as the average atmospheric flow of the polar stratosphere and as a specific manifestation of that circulation on a given day. For more context, read We're going to stop saying "polar vortex reversal".]

Footnotes

- It is likely that sudden stratospheric warming events occurred before the 1950s, but observational records of the stratosphere are sparse before then.

- These numbers only include sudden stratospheric warmings that occur in the middle of the winter (referred to as mid-winter warmings). We’ll discuss it more in a future post, but a final warming event occurs every spring as the polar vortex breaks down for the season. Those events are considered separate.