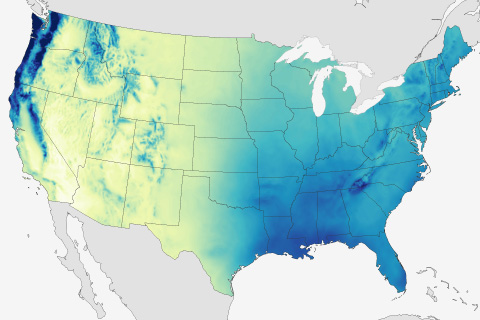

When it comes to what causes climate to vary over seemingly short distances, few things can compare to the influence of topography. This week in Beyond the Data, Jake Crouch talks about how climate scientists account for topography in interpreting climate patterns and trends.

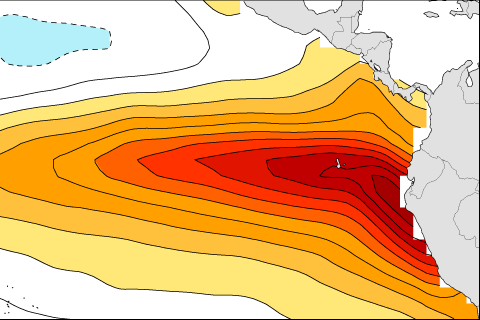

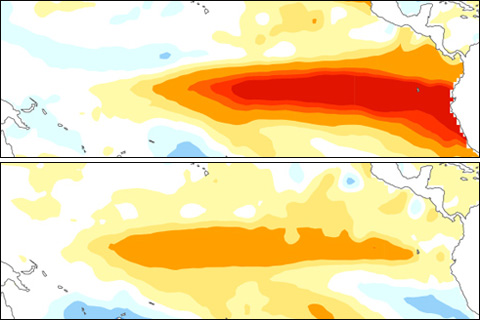

Guest blogger Ken Takahashi assesses the prospects for this El Niño to be an extreme one in the eastern tropical Pacific, like the 1982 and 1997 events were.

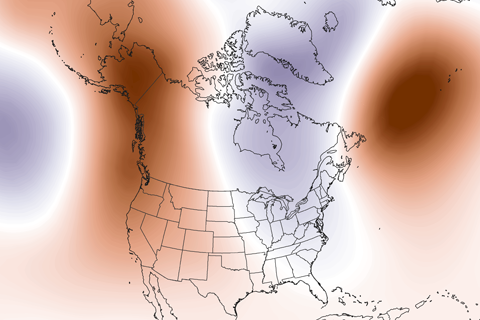

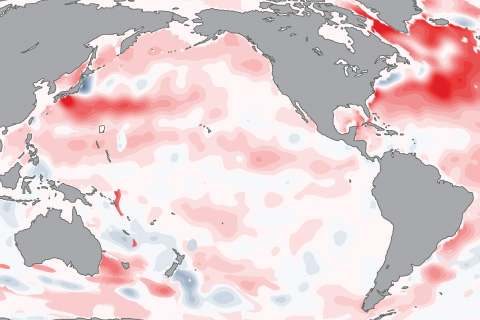

Guest blogger Dennis Hartmann makes the case that warm waters in the western tropical Pacific—part of the North Pacific Mode climate pattern—are behind the weird U.S. winter weather of the past two seasons.

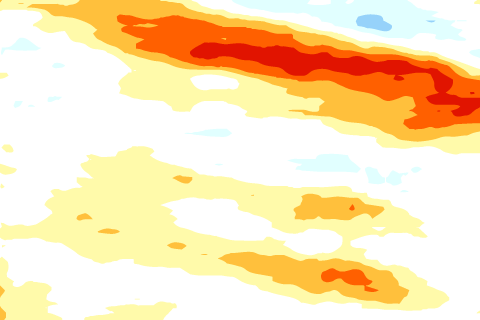

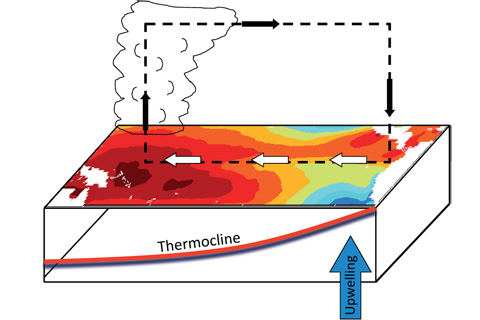

The tropical Pacific Ocean sloshes around like water in your bathtub. These waves are as important as the vortex of water that spirals down the drain.

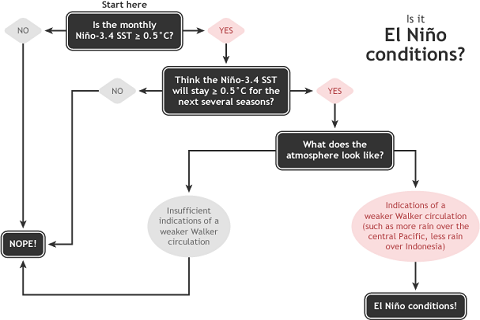

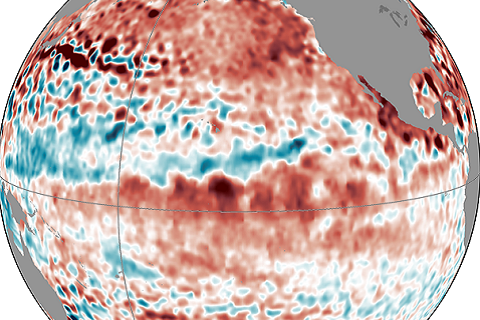

The ENSO Diagnostic Discussion just came out. Sea surface temperatures are solidly above average in the equatorial Pacific... so what's behind forecasters' decision not to declare El Niño conditions?

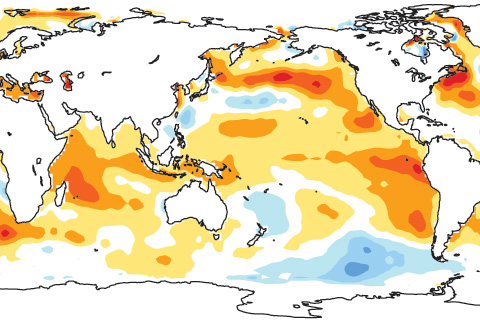

How can warming at Earth’s surface have slowed when energy accumulation is growing? The role of our oceans—including ENSO—is key.

How El Niño is like different flavors of ice cream. Seriously.

As of late August 2014, tropical atmospheric temperatures appear to be responding more strongly to the ocean than they typically do at this early stage of El Niño development.

If you are someone who wants more or stronger ENSO events in the future, I have great news for you–research supports that. If you are someone who wants fewer or weaker ENSO events in the future, don’t worry–research supports that too.

Forecasters are still calling for a 65% chance of El Nino conditions being met in the next few months. Isn't this late for the start of an ENSO event?