One of ENSO’s most important influences is to the Indian Monsoon—the large-scale circulation pattern that brings the Indian subcontinent the vast majority of its yearly rainfall. And while La Niñas tend to increase monsoon rainfall, the monsoon’s relationship with El Niño can be a little more complicated.

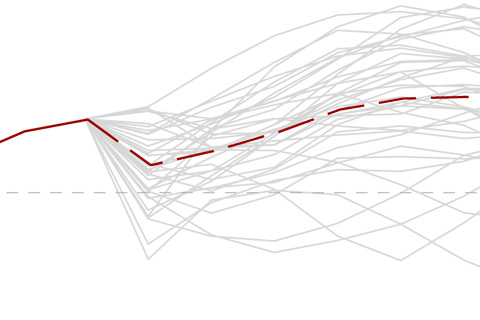

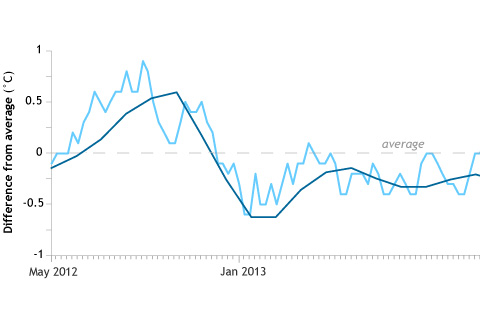

The Signal and the Noise is often mentioned in reference to ENSO forecasting and not just in reference to Nate Silver’s bestselling book. In fact, understanding what is signal and what is noise is critical to interpreting predictions from models and climate science in general.

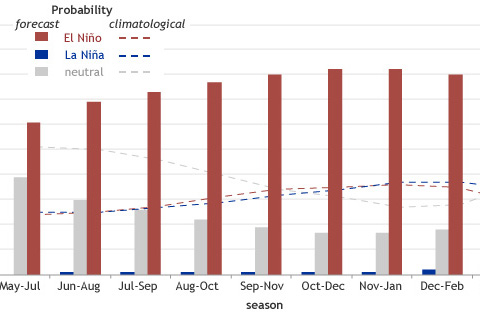

We’d like our forecasts—both weather and climate—to be simple and certain. Because of the fluid and chaotic nature of the ocean and atmosphere, however, forecasts are never about certainty: they’re about probability.

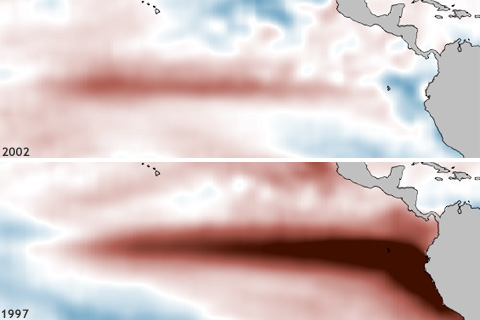

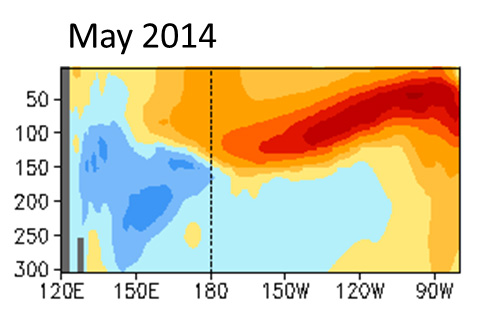

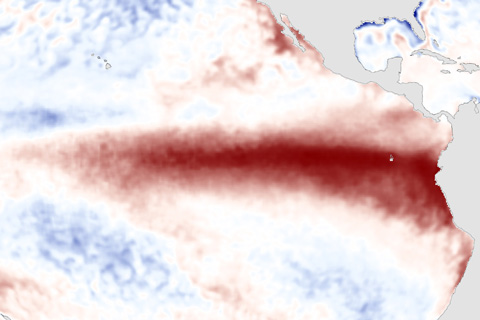

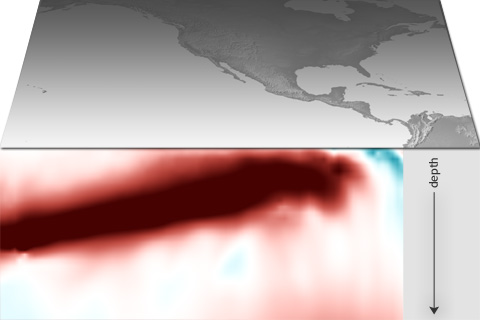

Chances that an El Niño will occur by summer are above 70%, hitting 80% by the fall. But subsurface temperature anomalies have tapered off some from earlier this spring, decreasing the odds the event will be as strong as the El Niño of 1997-98.

If the climate conditions that indicate ENSO are best measured as seasonal averages, will scientists wait for conditions to persist three months before declaring El Niño underway?

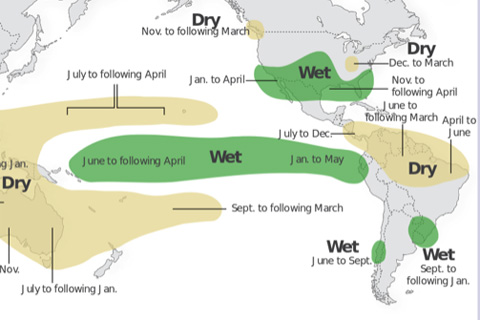

ENSO arises from changes across the tropical Pacific Ocean. So why does ENSO affect the climate over sizable portions of the globe, including some regions far removed from the tropical Pacific Ocean?

Though ENSO is a single climate phenomenon, it has three states, or phases, it can be in. The two opposite phases, “El Niño” and “La Niña,” require certain changes in both the ocean and the atmosphere because ENSO is a coupled climate phenomenon. “Neutral” is in the middle of the continuum.

A team of climate scientists—actual nerds!—discuss the current El Niño Watch and offer perspectives and analysis on the progression of El Niño.

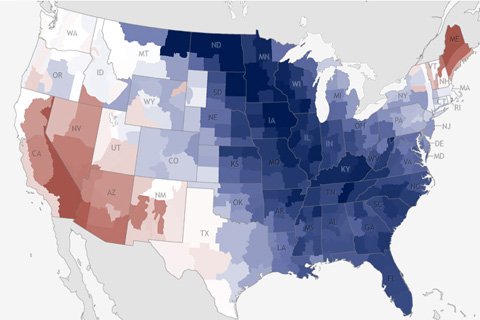

During March 2013, most of the eastern United States was notably cooler than average, with the exception of New England. Along the Rockies, temperatures were closer to normal.