What's the difference between global warming and climate change?

Global warming refers only to the Earth’s rising surface temperature, while climate change includes warming and the “side effects” of warming—like melting glaciers, heavier rainstorms, or more frequent drought. Said another way, global warming is one symptom of the much larger problem of human-caused climate change.

Global warming is just one symptom of the much larger problem of climate change. NOAA Climate.gov cartoon by Emily Greenhalgh.

Another distinction between global warming and climate change is that when scientists or public leaders talk about global warming these days, they almost always mean human-caused warming—warming due to the rapid increase in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from people burning coal, oil, and gas.

Climate change, on the other hand, can mean human-caused changes or natural ones, such as ice ages. Besides burning fossil fuels, humans can cause climate changes by emitting aerosol pollution—the tiny particles that reflect sunlight and cool the climate— into the atmosphere, or by transforming the Earth's landscape, for instance, from carbon-storing forests to farmland.

A climate change unlike any other

The planet has experienced climate change before: the Earth’s average temperature has fluctuated throughout the planet’s 4.54 billion-year history. The planet has experienced long cold periods ("ice ages") and warm periods ("interglacials") on 100,000-year cycles for at least the last million years.

Previous warming episodes were triggered by small increases in how much sunlight reached Earth’s surface and then amplified by large releases of carbon dioxide from the oceans as they warmed (like the fizz escaping from a warm soda).

Increases and decreases in global temperature during the naturally occurring ice ages of the past 800,000 years, ending with the early twentieth century. NOAA Climate.gov graph by Fiona Martin, based on EPICA Dome C ice core data provided by the Paleoclimatology Program at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information.

Today’s global warming is overwhelmingly due to the increase in heat-trapping gases that humans are adding to the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. In fact, over the last five decades, natural factors (solar forcing and volcanoes) would actually have led to a slight cooling of Earth’s surface temperature.

Global warming is also different from past warming in its rate. The current increase in global average temperature appears to be occurring much faster than at any point since modern civilization and agriculture developed in the past 11,000 years or so—and probably faster than any interglacial warm periods over the last million years.

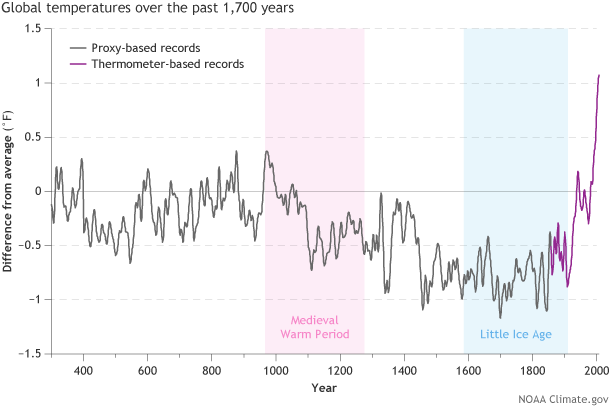

Temperatures over most of the past 2000 years compared to the 1961-1990 average, based on proxy data (tree rings, ice cores, corals) and modern thermometer-based data. Over the past two millenia, climate warmed and cooled, but no previous warming episodes appear to have been as large and abrupt as recent global warming. NOAA Climate.gov graph by Fiona Martin, adapted from Figure 34.5 in the National Climate Assessment, based on data from Mann et al., 2008.

New understanding required new terms

Regardless of whether you say that climate change is all the side effects of global warming, or that global warming is one symptom of human-caused climate change, you’re essentially talking about the same basic phenomenon: the build up of excess heat energy in the Earth system. So why do we have two ways of describing what is basically the same thing?

According to historian Spencer Weart, the use of more than one term to describe different aspects of the same phenomenon tracks the progress of scientists’ understanding of the problem.

As far back as the late 1800s, scientists were hypothesizing that industrialization, driven by the burning of fossil fuels for energy, had the potential to modify the climate. For many decades, though, they weren’t sure whether cooling (due to reflection of sunlight from pollution) or warming (due to greenhouse gases) would dominate.

By the mid-1970s, however, more and more evidence suggested warming would dominate and that it would be unlike any previous, naturally triggered warming episode. The phrase “global warming” emerged to describe that scientific consensus.

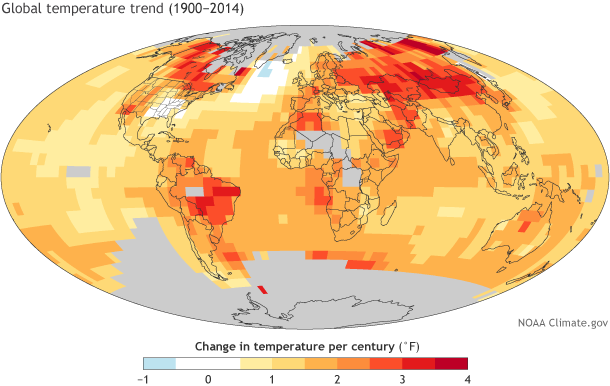

Change in temperature (degrees per century) from 1900-2014. Gray areas indicate where there is insufficient data to detect a long-term trend. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on NOAAGlobalTemp data from NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information.

But over subsequent decades, scientists became more aware that global warming was not the only impact of excess heat absorbed by greenhouse gases. Other changes—sea level rise, intensification of the water cycle, stress on plants and animals—were likely to be far more important to our daily lives and economies. By the 1990s, scientists increasingly used “human-caused climate change” to describe the challenge facing the planet.

The bottom line

Today’s global warming is an unprecedented type of climate change, and it is driving a cascade of side effects in our climate system. It’s these side effects, such as changes in sea level along heavily populated coastlines and the worldwide retreat of mountain glaciers that millions of people depend on for drinking water and agriculture, that are likely to have a much greater impact on society than temperature change alone.

References

Broecker, W. S. (1975). Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming? Science, 189(4201), 460–463. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.189.4201.460

Climate Data Primer. Climate.gov.

Gillett, N. P., V. K. Arora, G. M. Flato, J. F. Scinocca, and K. von Salzen, 2012: Improved constraints on 21st-century warming derived using 160 years of temperature observations. Geophysical Research Letters, 39, 5, doi:10.1029/2011GL050226. [Available online at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2011GL050226/pdf]

Global Warming FAQ. Climate.gov.

How do we know the world has warmed? by J. J. Kennedy, P. W. Thorne, T. C. Peterson, R. A. Ruedy, P. A. Stott, D. E. Parker, S. A. Good, H. A. Titchner, and K. M. Willett, 2010: [in "State of the Climate in 2009"]. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 91 (7), S79-106.

Huber, M., and R. Knutti, 2012: Anthropogenic and natural warming inferred from changes in Earth’s energy balance. Nature Geoscience, 5, 31-36, doi:10.1038/ngeo1327. [Available online at http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v5/n1/pdf/ngeo1327.pdf]

Jouzel, J., et al. 2007. EPICA Dome C Ice Core 800KYr Deuterium Data and Temperature Estimates. IGBP PAGES/World Data Center for Paleoclimatology Data Contribution Series # 2007-091. NOAA/NCDC Paleoclimatology Program, Boulder CO, USA.

Mann, M. E., Zhang, Z., Hughes, M. K., Bradley, R. S., Miller, S. K., Rutherford, S., & Ni, F., 2008: Proxy-based reconstructions of hemispheric and global surface temperature variations over the past two millennia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(36), 13252-13257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805721105.

Melillo, Jerry M., Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and Gary W. Yohe, Eds., 2014: Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, 841 pp. doi:10.7930/J0Z31WJ2. Online at: nca2014.globalchange.gov

National Academy of Sciences, Climate Research Board, Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment (Jules Charney, Chair). (1979). Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. [Online (pdf)] http://web.atmos.ucla.edu/~brianpm/download/charney_report.pdf

Walsh, J., D. Wuebbles, K. Hayhoe, J. Kossin, K. Kunkel, G. Stephens, P. Thorne, R. Vose, M. Wehner, J. Willis, D. Anderson, V. Kharin, T. Knutson, F. Landerer, T. Lenton, J. Kennedy, and R. Somerville, 2014: Appendix 4: Frequently Asked Questions. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 790-820. doi:10.7930/J0G15XS3

Weart, S. (2008). Timeline (Milestones). In The Discovery of Global Warming. [Online] American Institute of Physics website.