Previously, we showed how the southern African monsoon took a while to get going across Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Zambia. The lack of rain led to rapidly deteriorating ground conditions during November. And then? It started to rain heavily. And it hasn’t stopped.

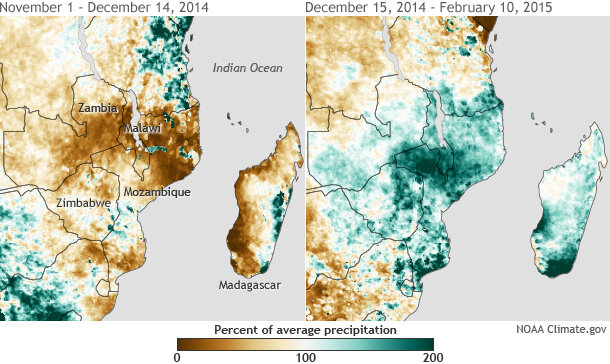

Percent of normal rainfall for southern Africa from November 1–December 14, 2014 (left) and December 15-February 10, 2015 (right). The monsoon season produced very little rain early in the season, but then unleashed a deluge. Map by NOAA Climate.gov based on CPC’s African Rainfall Climatology (ARC). ARC’s historical record dates back to 1983.

The result? A completely flipped map of rainfall anomalies (figure 1). Where there were substantial early monsoon season deficits, there are now crippling rainfall surpluses. Where ground conditions deteriorated, there was rebirth and then inundation.

Rains from the middle of December to the end January were 125-400% above-average, more than 8 inches more than normal, completely eroding any deficits that developed in November. According to the Africa Rainfall Climatology dataset, for a large portion of central/northern Mozambique and southern Malawi, it was the wettest December 15- February 10 on record dating back to 1983. Vegetation rebounded positively, to a point.

Satellite-based Vegetation Health Index (VHI) from October 14, 2014–February 4, 2015. Scant rainfall early in the monsoon led to very stressed vegetation (dark brown) in November and early December, but hints of green (healthy vegetation) had begun to emerge in January and early February. In Malawi, brown patches near the end of the time period may be the result of inundation, not just earlier dryness. Tan areas represent average vegetation conditions. White patches are lakes and other small water bodies. Map by Dan Pisut, based on NOAA NESDIS satellite data.

With that much water falling, though, flooding was inevitable. Rivers like the Shire, Licungo, Zambezi, Mazoe, Pungue and Save Rivers burst their banks in Malawi and Mozambique. According to reports from the United Nations, UNICEF, and the Malawian government, almost 64,000 hectares (247 square miles) of land flooded in Malawi, 40,000 hectares (154 square miles) of which was farmland. The floods displaced 230,000 people and killed more than 200.

Media reports also indicated that in Mozambique, 52,000 people were forced out of their homes, with Mozambique’s disaster management agency INGC reporting a death toll of 117 people. Flooding in Madagascar displaced 45,000 and, combined with the impacts from Tropical Storm Chedza in January, killed 74 people. Flooding extended into Zimbabwe as well, killing 18 people.

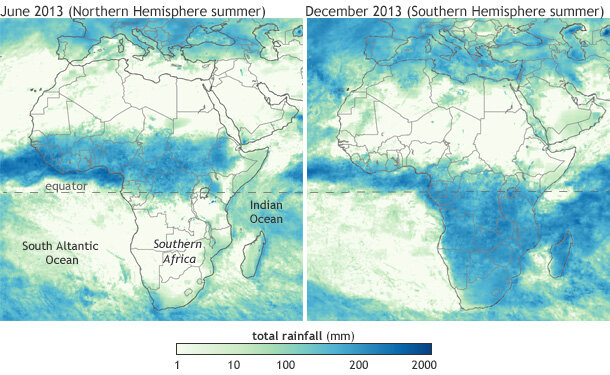

The location of rainfall in southern Africa is the epicenter in a complex game of tug of war between large areas of semi-permanent high pressure systems over the South Atlantic and South Indian Oceans and the seasonal progression south of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The ITCZ marks the region where the trade winds from the northern and southern hemisphere meet. Where they meet is an area of rising air and rain showers. The latitude of the rainbelt shifts north and south of the equator with the changing of the seasons.

Monthly rainfall over Africa in June 2013 (left) and December 2013 (right). The interaction between the African landmass, high pressure systems over the surrounding oceans, and the seasonal shift of the global tropical rain belt leads to southern Africa's rainy and dry seasons. Map by NOAA Climate.gov, based on NASA satellite-based rainfall images from NEO.

Plus, for good measure, tropical cyclones in the Indian Ocean or Mozambique Channel can shift where the rains fall by dragging and keeping the ITCZ farther south than normal. (Two storms have formed in the Mozambique Channel since January 1: Chedza and Fundi.) For the better part of the past two months, southeastern Africa has been the bulls-eye for rising air and heavy rain.

And even though rains were not quite as heavy at the end of January, they have picked up again to start February. Almost 8 inches of rain (200mm) fell in the central Mozambique city of Caia from January 27-February 2, while 3.6 inches (92mm) was recorded in Malawi’s second largest city, Blantyre, in the flood-affected south of the country. During the first week of February (February 3-9) 8-10 inches of rain (200-250mm) was recorded in western Madagascar and the city of Nampula in northern Mozambique thanks to thunderstorms associated with a developing tropical storm in the Mozambique Channel.

The southern African monsoon season is long, up to 6 months in some locations. As such, it can have many ups and downs along the way. But the 2014-2015 monsoon season has certainly been erratic for Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, Madagascar and Zimbabwe, and there are still several months left to go.