ENSO and the southwest United States "megadrought”

This is a guest post by Hannah Bao, a recent graduate of the University of Maryland’s Atmospheric and Oceanic Science Department. Hannah is currently enrolled in UMD’s Data Science M.S. program. She developed this piece based on a longer research paper she did for a class.

El Niño and La Niña (collectively, ENSO, the El Niño/Southern Oscillation) affect global rain/snow and temperature patterns, making certain outcomes more likely in some regions. For example, winters with La Niña—cooler-than-average surface waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific—tend to be drier than average along the southern third of the U.S. While this is certainly not always the case, ENSO still gives us a valuable early heads-up of an increased chance of certain outcomes. (Here at the ENSO Blog, we have several posts discussing these precipitation relationships.) In this post, I’ll cover the relationship between ENSO and drought in the Southwest.

The state of the Southwest

The atmospheric river events of winter 2022–23, and more recently those that swept through the U.S. West this past winter (2023-24), delivered much-needed moisture across portions of the southwest United States, a region afflicted with severe drought over the past two decades. Back in mid-March 2024, around 25% of the Southwest was in some level of drought. For comparison, at least 90% of the entire Southwest experienced drought conditions around that same time in 2021 and 2022.

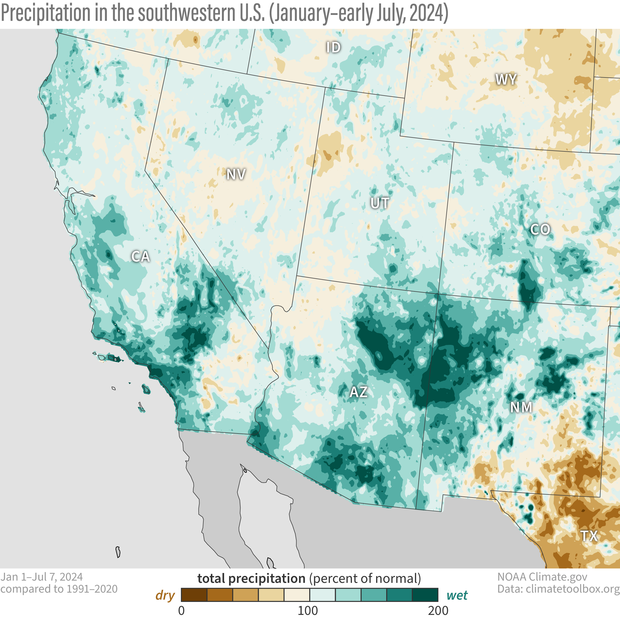

This map shows July 2024 precipitation (total rain and snow) received across the United States as percent of normal (1991-2020 average). Places where precipitation was below normal are brown; places where it was above normal are blue-green. NOAA Climate.gov map from https://climatetoolbox.org data.

However, the so-called “drought-buster” events of the previous two winters, coupled with the 2023–24 El Niño, have not been enough to entirely eliminate the dryness over some parts of the region. Data from the U.S. Drought Monitor indicates that about 16% of the Southwest is in some level of drought as of early August 2024, including 20% of Arizona and roughly 48% of New Mexico experiencing drought conditions.

Click and hold bar to drag slider. (left) In 2021, extreme (bright red) to exceptional drought (dark red) was widespread across the U.S. Southwest. Even following a series of "atmospheric river" events in the winters of 2022-23 and 2023-24, most of the region (right) remained abnormally dry (yellow) or in some level of drought in August 2024. Images from the U.S. Drought Monitor Project via Drought.gov.

With a 66% chance for La Niña to develop in September-November 2024, you may be wondering: what does this mean for drought in the southwest United States? Are La Niña conditions likely to improve or worsen the severe multi-year drought persisting in portions of the region? Stay tuned to find out!

Drought is a complex phenomenon with many components, including rainfall, snowpack, temperature, land-use management, and other elements. However, we can begin to answer these questions by studying the historic links between ENSO and drought in the U.S. Southwest. In this blog, we will address:

-

How does ENSO typically impact Southwest winter precipitation?

-

How is ENSO impacting the 21st-century drought in the Southwest?

We’ll look at several scientific studies that have had important contributions to our understanding of ENSO impacts in the Southwest.

How does ENSO typically impact Southwest winter precipitation?

In a 1999 study (1), Dr. Daniel Cayan of Scripps Institution of Oceanography and his team found that the frequency of daily high precipitation and high stream flow over the western U.S. are strongly influenced by ENSO phase. They used daily wintertime precipitation and late-winter to early-summer stream flow from 1948 to 1995, retrieved from several hundred observing stations across 11 Western U.S. states.

Dr. Cayan’s team found that El Niño years are linked to more days than average with high daily precipitation and streamflow in the Southwest; La Niña years showed an approximately opposite pattern. Heavier precipitation events also tend to occur more frequently during El Niño years and less frequently during La Niña years over the Southwest.

These findings agree with those from a 2002 review (2) conducted by Dr. Paul Sheppard and colleagues. Dr. Sheppard’s team concluded that El Niño is generally associated with cooler and wetter winters in the Southwest, whereas La Niña is linked to drier, warmer winters over the region. Another 2002 study (3), led by Dr. Julia E. Cole and colleagues, traces the La Niña and Southwest drought connection back to the 1800s using coral records! Together, these studies seem to point towards La Niña events as potential drivers of drought over the Southwest during the latter half of the 20th century to early 21st century. This naturally prompts the question: has this pattern continued into recent decades?

Dry conditions drop water levels in Utah. Credit: Drought.gov

ENSO’s role in the 21st-century U.S. Southwest drought

Dry episodes are not uncommon for the Southwest, as discussed in this 2010 study (4) and the 2002 review by Dr. Sheppard’s team. However, recent research (5) has shown that the 21st century drought is one of the worst droughts within the last 1200 years in the region. As southwestern U.S. precipitation patterns have exhibited a strong response to ENSO phase in the past, it’s worth examining ENSO’s role in the recent drying observed over the region.

A 2019 study (6) analyzing the effects of ENSO, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), and the Atlantic Multi-Decadal Oscillation (AMO) on drought variability over the western United States from 1948 to 2009 found that the Southwest tends to experience more dry episodes during La Niña years than El Niño years—consistent with the studies discussed earlier in this post. This study, led by Dr. Peng Jiang of the Desert Research Institute and colleagues, explored the response of winter consecutive dry days to ENSO.

More recently, a 2022 study (7) led by Dr. Richard Seager examined the roles of tropical Pacific sea surface temperature (SST), internal atmospheric variability, and anthropogenic change in driving the severe Summer 2020 to Spring 2021 drought over southwestern North America. Using observational SST and precipitation data, they found that the onset of the drought coincided with a La Niña developing between June to August of 2020. Anomalously cool tropical Pacific SSTs and circulation anomaly patterns, typical of La Niña events, corresponded to reduced precipitation from Fall 2020 to Spring 2021, suggesting La Niña as a potential driver of drought during this period. Dr. Seager and colleagues concluded that a combination of internal atmospheric variability and La Niña were largely responsible for fueling the extreme dry conditions across the Southwest from Fall 2020 to Spring 2021. Also, as we can see from the drought monitor images above, the drought conditions across much of the Southwest continued through the third consecutive La Niña winter, 2022–2023.

Paleoclimate data have uncovered multiple megadroughts in the American Southwest. Credit: National Climate Assessment

Limitations!

So…will a potential La Niña bring drier conditions to already-parched portions of the Southwest this coming winter 2024-25? The current Climate Prediction Center outlook favors below-average precipitation for the region.

Based on our understanding of typical ENSO teleconnections over the Southwest and the studies discussed above, it’s entirely possible.

However, as always, let’s keep in mind some key limitations and proceed with caution. First, our observed SST record for monitoring ENSO is very limited (around 74 years!). Second, ENSO explains only a fraction of the variability of wintertime southwestern U.S. precipitation. Other large-scale climate phenomena such as the PDO, ENSO’s interactions with other climate modes, climate change, and other factors may all influence drought conditions in the Southwest to varying degrees.

It is also an open question to what extent the Southwest megadrought can be attributed to ENSO. Answering this important question requires more research, and ideally, a longer observational record.

Lead reviewer: Emily Becker

References

- Cayan, D. R., Redmond, K. T., & Riddle, L. G. (1999). ENSO and hydrologic extremes in the western United States. Journal of Climate, 12(9), 2881-2893.

- Sheppard, P. R., Comrie, A. C., Packin, G. D., Angersbach, K., & Hughes, M. K. (2002). The climate of the US Southwest. Climate Research, 21(3), 219-238. 10.3354/cr021219

- Cole, J. E., Overpeck, J. T., & Cook, E. R. (2002). Multiyear La Niña events and persistent drought in the contiguous United States. Geophysical Research Letters, 29(13), 25-1. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL013561

- Woodhouse, C.A., Meko, D.M., MacDonald, G.M., Stahle, D.W., & Cook, E.R. (2010). A 1200-year perspective of 21st century drought in southwestern North America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(50), 21283-21288. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911197107

- Williams, A. P., Cook, B. I., & Smerdon, J. E. (2022). Rapid intensification of the emerging southwestern North American megadrought in 2020–2021. Nature Climate Change, 12(3), 232-234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01290-z

- Jiang, P., Yu, Z., & Acharya, K. (2019). Drought in the Western United States: its connections with large-scale oceanic oscillations. Atmosphere, 10(2), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10020082

- Seager, R., Ting, M., Alexander, P., Nakamura, J., Liu, H., Li, C., & Simpson, I. R. (2022). Mechanisms of a meteorological drought onset: summer 2020 to spring 2021 in southwestern North America. Journal of Climate, 35(22), 3767-3785. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-22-0314.1

Comments

Droughts in the...

Southwest US are caused by decades of a Negative PDO and a positive AMO. The question is when will this reverse ?

Interesting post

So, it sounds like La Nina contributes to drought in the Southwest while El Nino reduces the odds of that - irrespective of their effects on the monsoon season there. Is that correct?

Thanks to Ms. Bao for sharing what she learned in that class with the rest of us.

That is correct!

That is correct!

But why so many La Nina?

My thanks to Ms. Bao forher comprehensive article on the mega drought. As a NM resident, we are feeling this still. No atmospheric rivers for us, yet.

I do wonder, how is the melting polar ice effecting these years-long La Nina cycles? Does the cold water from melting poles increase the chance of a la Nina?

Hi Amanda, While the melting…

Hi Amanda,

While the melting polar ice is having all sorts of impacts across the Arctic, luckily it won't have much influence on La Nina.

Good to know, thanks!

Good to know, thanks!

Add new comment