September 2024 ENSO update: binge watch

The tropical Pacific is still in neutral, but nature continues giving us signs that La Niña is on the way, and our La Niña Watch remains. Forecasters estimate a 71% chance that La Niña will emerge during September–November and expect it will persist through the Northern Hemisphere winter. A weak La Niña is the most likely scenario.

Opening credits

While there are no plot twists since Tom’s August post—frequent readers could be forgiven for fast-forwarding this month’s update—that 71% chance of La Niña developing this autumn is a small upward tick. Also, the slower-than-expected development of La Niña is a great example of how the short-term (subseasonal) and very long-term (climate change) complicate seasonal outlooks. I’ll run the numbers in a minute, after a word from our sponsor.

Hello folks! Do you wish you could get a heads-up about what your winter rain, snow, and temperature conditions might be like? Ask your forecaster about ENSO, the El Niño/Southern Oscillation! This seasonal climate phenomenon is made from the surface temperature of the tropical Pacific, including warmer-than-average water (El Niño) and cooler-than-average water (La Niña), and can be predicted months in advance. ENSO changes global atmospheric circulation in known ways; common side-effects may include shifts in the jet stream and changes in global temperature and precipitation patterns, droughts, and heatwaves.

Back to our regularly scheduled program

ENSO forecasters get their information from two general areas: climate prediction models and current observed conditions in the ocean and atmosphere. Climate models are up first, today. (See footnote.)

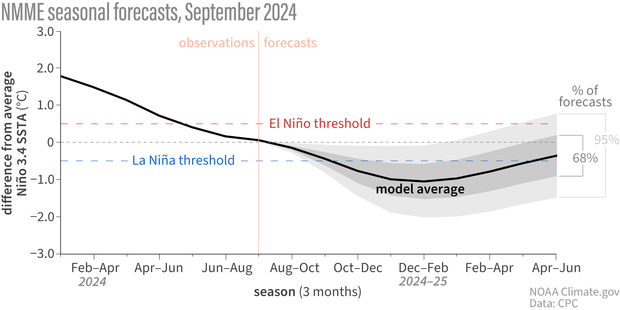

Line graph showing observed and predicted temperatures (black line) in the key ENSO-monitoring region of the tropical Pacific from early 2024 though spring 2025. The gray shading shows the range of temperatures predicted by individual models that are part of the North American Multi Model Ensemble (NMME, for short). Most of the shading appears below the dashed blue line by the fall, meaning most models predict that temperature in the Niño-3.4 region of the tropical Pacific will be cooler than average by at least 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 degrees Fahrenheit)—the La Niña threshold. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on data provided by Climate Prediction Center.

The North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) is a collection of computer models that take information about current global conditions and apply physical equations to make predictions about upcoming weather and climate. For more about the NMME, check out this ENSO Blog post and this recent one from our friends at Seasoned Chaos.

This set of climate models has been predicting the development of La Niña since last winter, and continues to do so, although it’s taking a little longer than initially expected. This isn’t particularly surprising, since predictions made in the spring are often less accurate than predictions made at other times of the year. Overall, though, the models’ prediction of La Niña this upcoming winter has been consistent, including from last month to this month, providing continued confidence in the forecast despite the slowdown.

Reality TV

Time to check in with a few of our favorite characters. Our primary metric for ENSO, the surface temperature of the tropical Pacific Ocean in the Niño-3.4 region, was about 0.1 °C cooler than the long-term average (long-term = 1991–2020) in August, according to the ERSSTv5 dataset. This is solidly neutral—the La Niña threshold is 0.5 °C cooler than average—and only a small drop from July.

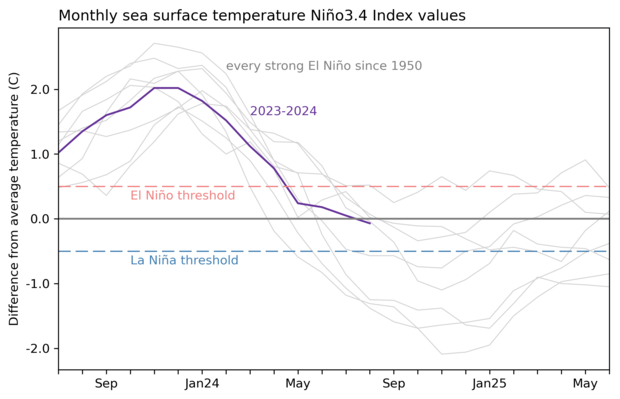

2-year history of sea surface temperatures in the Niño-3.4 region of the tropical Pacific for all strong El Niño events since 1950 (gray lines) and the recent (2023-24) event (purple line). Five of the eight gray lines dip below the dashed blue line (the La Niña threshold) in the winter following the El Niño. The 2023-24 event appears headed in the same direction. Graph by Emily Becker based on monthly Niño-3.4 index data from CPC using ERSSTv5.

The winds over the tropical Pacific play an important role in ENSO’s dramatic arc. When the near-surface winds in the tropics—the trade winds—are stronger, they cool the surface and keep warmer water piled up in the far western Pacific. They can also trigger an upwelling Kelvin wave, an area of cooler-than-average water under the surface that moves from west to east. Throughout August, the trade winds were stronger than average across most of the tropical Pacific, helping to maintain the gradual surface cooling tendency and to bolster the amount of cooler water under the surface. This cooler subsurface water will provide a source to the surface over the next few months.

Beneath the surface of the tropical Pacific Ocean at the equator, a deep pool of cooler-than-average (blue) waters has been building up over the past couple of months (July 12–Sept. 5, 2024). This pool of relatively cool water is a key factor behind the prediction for La Niña later this fall and winter. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on analysis from Michelle L'Heureux, Climate Prediction Center.

Character development

We started this La Niña Watch party back in February. Looking back at that forecast, the probability of La Niña developing by June–August was about 55%, with about a 42% chance of ENSO-neutral during that period. These probabilities mean that La Niña’s development in June–August was favored, but there was still a good chance that neutral would linger. As it turned out, the June–August average sea surface temperature in the Niño-3.4 region, the “Oceanic Niño Index,” was 0.1 °C below average, in the neutral range.

So why is La Niña behind schedule? Honestly, nature is wild and crazy and it amazes me that we can predict anything ever, especially many months in advance. In this case, though, there are a couple of complicating factors we can point to. The first is our old frenemy, short-term variability, or, essentially, unpredictable weather events that complicate seasonal or longer predictions. For example, just a few periods of weaker trade winds can delay surface cooling. Unfortunately, predicting such short-term variations is an ongoing challenge, and currently we can only predict these trade wind fluctuations a week or so in advance.

On the other side of the timeline, we have climate change. The global ocean temperatures are still way above average, and they are predicted to drop only slightly over the next several months. We don’t yet have a clear picture of how global warming may affect ENSO in general, or the development of La Niña this year in specific.

Coming up on La Niña Watch

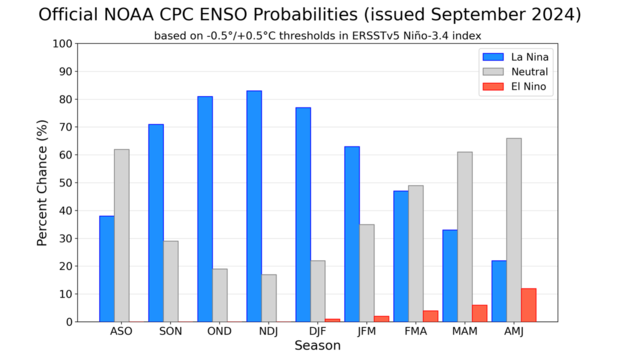

That said, the most likely outcome is still that La Niña will be in place this winter, with slightly greater than 80% chance of La Niña in November–January, probably a weaker event (see strength probabilities here).

Out of the three climate possibilities—La Niña, El Niño, and neutral—forecasts say that neutral conditions are the most likely for the August–October season (tall gray bar above the ASO label, slightly over 60 percent chance). By the September-November (SON) season, La Niña has the highest chance of occurring (blue bar, 71 percent chance). NOAA Climate Prediction Center image.

A weak La Niña wouldn’t play as large a part in steering global atmospheric circulation patterns, meaning a lower chance of La Niña’s typical impacts on winter conditions. However, even a weak La Niña can nudge the winter climate and would likely factor into CPC’s winter outlook.

Stay tuned here for recaps and predictions about your favorite program, ENSO!

Footnote

There are two kinds of prediction models, dynamical and statistical. The model information I discuss in this post is from dynamical models. Statistical models use historical observations and their relationships to predict how conditions might evolve. Statistical models do not use physical equations, but rather statistical formulations that produce forecasts based on a long history of past observations of sea surface temperature, atmospheric pressure, subsurface temperature, and others. Statistical models have been around longer than dynamical models, because the dynamical ones require high performance computers.

Comments

Interesting...

but this came up from years ago. I looked up the PDO in December 1917, and the PDO was a negative 0.52. La Nina was in place in the Tropical Pacific. I read that was the coldest and Snowiest begin to Winter 1917 - 18 that was ever recorded in the CONUS. Interesting that in January 1918 the PDO was a positive 0.42. Apparently, low readings in the PDO plus La Nina was responsible for the very harsh Winter 1917 - 18. I also looked up the AMO (AMV) and from 1880, and has been slowly climbing from that year to now. The AMO in 1917 - 18 was strongly negative and now strongly positive and the PDO is a negative 2.88. Appreciate any thoughts on this scenario.

La Nina

Seems the west tropical pacific is cooling. What does the RONI figures look like? Seems the Nino 3.4 is going to be in the weak to moderate range. Do you see an enhanced La Nina based on the surrounding SSTs and warm in the ocean?

La Nina effects

This La Nina looks like a weak one based on the Nino 3.4 ssts. is there anything out there that may enhance La Nina's effects this winter. The warm temperatures in the Western Tropical Pacific are cooling. What do the RONI numbers show?

The Relative Oceanic Nino…

The Relative Oceanic Nino Index for June–August was -0.44, so quite a bit cooler than the Oceanic Nino Index. As we go into the Northern Hemisphere cool season, it will be interesting to see if these numbers remain separated. The RONI, which takes the entire tropical oceans into account, may be a useful metric to understand ENSO in a warming world. It is not the official NOAA metric for ENSO and is still in the testing stage.

LaNina

Thanks Emily.

What is out there that may influence La Nina's effects and make it a stronger event than what is measured by the SSTs in the Nino 3.4?

Thoughts on post

1. As usual, this was an interesting and informative post

2. Your "word from our sponsors" part seemed a bit like one of those TV drug ads, where they introduce some medicine and talk about how wonderful it is, but then describe its side effects really quickly, in a manner that sounds kind of funny. (Use of xxx has been linked to such problems as finger cancer, growing a tail, and minor cases of death. See your doctor for details.)

So, you could almost have done something like that for this: (spoken quickly) "Following the ENSO blog regularly has been found to result in users understanding this atmospheric phenomenon a little better, rolling their eyes at news reports sensationalizing El Nino and La Nina, and amazing their friends and family with their weather knowledge. Individual user experiences may vary. See your friendly ENSO blogger for details."

All joking aside, this was an educational post. Thanks for your hard work.

And thank you for this!! I…

And thank you for this!! I hope our readers make sure to read the fine print down here in the comments! :-)

la Nina Strength

Hi Emily,

great posts as always. Just read through the BOM ENSO update that was issued today. They are forecasting based on modeling a weak la nina possibly around the .8 range. Is there a way to measure the relative strength of a La Nina which may be enhanced due to the surrounding warm SSTs? Does the SOI measure the relative strength?

Hi Bob - we do track the…

Hi Bob - we do track the relative Oceanic Nino Index, which takes into account the entire tropical oceans, here. This isn't the official NOAA metric for ENSO, since we need to do some more research to understand the impacts. Recently, there is a large difference between the Relative ONI and the original-flavor ONI. It will be interesting to monitor both as we head into this likely La Nina winter.

La Nina

Thanks Emily!

Hurricanes and La Nina

Question: Did something just change with water temperatures or winds in the Pacific? I ask because it seems like the tropical Atlantic suddenly seem to have gotten more active.

To the extent of my…

To the extent of my knowledge, we don't have a clear explanation of why this Atlantic hurricane season had such an extended quiet period, followed by this active period. There will be a lot of research to uncover what happened this year and to understand if it could be predicted.

mateojose@gmail.com

Or, maybe it had some coffee...

On a more serious note, I hope that whoever researches this is able to get some answers, so that future forecasts get a little better.

Regardless, thanks for the reply.

NMME

The October run came out. NMME looks ugly for California and many other places in the continental US as far a s precipitation goes and temperature wise almost the entire continental US looks warmer than normal.

Warm SSTs

There currently is a very warm large blob of water west of 180 in the North Pacific. If this warm SST blob persists, could it affect our weather?

North Pacific SST impacts

That's a good question. On one hand, many studies have struggled to find robust impacts of extratropical sea surface temperature anomalies on midlatitude weather (unlike tropical sea surface temperature anomalies that directly impact atmospheric convection and midlatitude Rossby waves). On the other hand, there have been some indications that North Pacific sea surface temperature anomalies, especially in connection with the Kuroshio-Oyashio extension, could have some impact on our weather. For example, this recent study led by one of my postdocs suggests that a warm North Pacific like what we see now is associated with enhanced North Pacific atmospheric blocking, which impacts North American weather. So, I would say the jury is still out!

Thanks Nathaniel

Thanks Nathaniel for that explanation!. Weather geeks love to look at the overall SST patterns in the Pacific other than ENSO and compare them to prior years SSTs to come up with a winter forecast. I've always felt that was a bit of folly.

SST patterns

Yeah, there's a reason why we focus on ENSO in this blog and why seasonal forecasts from dynamical models usually resemble the typical ENSO impacts (with the addition of the trend for temperature) - the impacts of other sea surface temperature patterns tend to be minor. However, that doesn't mean that the impacts of these other patterns are always negligible, and it doesn't mean that our models aren't missing something important. The bottom line, though, is that the atmospheric response to tropical sea surface temperature anomalies, especially from ENSO, is often the dominant seasonal forecast signal.

Add new comment