October 2024 ENSO update: spooky season

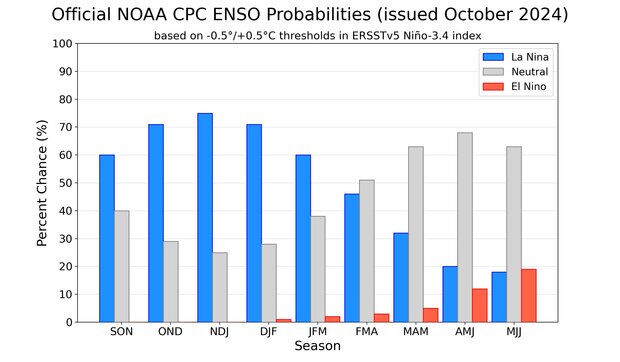

The tropical Pacific Ocean reflected neutral conditions—neither El Niño nor La Niña—in September. Forecasters continue to favor La Niña later this year, with an approximately 60% chance it will develop in September–November. The probability of La Niña is a bit lower than last month, though, and it’s likely to be a weak event.

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore

La Niña is the cool phase of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a pattern of alternating warmer (El Niño) and cooler surface waters in the tropical Pacific. Rising warm air in the tropics is what drives global atmospheric circulation, and therefore the jet stream, storm tracks, and resulting temperature and rain patterns. ENSO’s varying sea surface temperature changes where the strongest rising air motion occurs, hence changing global atmospheric circulation. ENSO is predictable several months in advance, and when you couple that predictability with our knowledge of how it changes global patterns, you get an early picture of potential upcoming weather and climate patterns.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling

Let’s take a spin through recent conditions in the tropical Pacific. The threshold for La Niña is a sea surface temperature in the Niño-3.4 region in the central equatorial Pacific that is equal to or more than 0.5 °C below the long-term average. (Currently, long-term is 1991–2020.) The most recent weekly measurement of the temperature difference from average in the Niño-3.4 region was -0.3 °C, and the September average was also -0.3 °C.

Hurricane Helene’s devastating impacts on the Asheville, NC, region affected NOAA’s data center—see the footnote for details on our new data sources this month. Michelle and CPC’s Caihong Wen did extensive testing and determined that the temporary replacements have historically been very close to the ones we usually use, so we’re confident that ENSO-neutral conditions are still in place.

This animation shows weekly sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean compared to average from July 1–September 29, 2024. Orange and red areas were warmer than average; blue areas were cooler than average. Warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the key ENSO-monitoring region of the tropical Pacific (outlined with black box) have started to be replaced by cooler-than-average waters—a sign that La Niña may be brewing. NOAA Climate.gov animation, based on Coral Reef Watch Data and maps from NOAA View. View the full-size version in its own browser window.

There has been a region of cooler-than-average water in the central-eastern tropical Pacific in recent weeks, as you can see above, but it’s not quite crossing the threshold. Some aspects of the tropical atmosphere are still reflecting neutral, too. There was a region of stronger-than-average trade winds in the east-central tropical Pacific and a little bit of reduced rainfall over the central Pacific, but overall, no strong, distinct pattern of stronger-than-average trade winds or increased rainfall over Indonesia as we’d expect during an established La Niña. In fact, a couple weeks of average to weaker-than-average trade winds during September allowed the surface to warm a bit.

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

If it seems like we’ve been stuck here in neutral for longer than we expected—we have! Last winter, models were predicting that La Niña would develop rapidly after the end of El Niño 2023–24. So what happened? Why are we still waiting? Didn’t I just say ENSO is predictable?

Not exactly a pallid bust of Pallas.

ENSO is predictable, but only in the big picture, meaning seasonal averages or longer. The signals that tell us that El Niño or La Niña are on the way, such as a large amount of cooler or warmer water under the ocean surface, or a particularly strong, long-lasting shift in the trade winds, are reliable indicators. Also, our computer climate models, which look at current conditions and make predictions based on mathematical and physical equations, are pretty good, especially after the spring barrier (a time of year when predictions are especially difficult).

However, small, short-term fluctuations, such as the weaker equatorial trade winds that occurred during September, can’t be predicted more than a couple of weeks (at best) in advance. They tend to have a disproportionate impact during borderline, more marginal situations when we are hovering near our ENSO thresholds. These small fluctuations can tip the scales one way or the other. In this case, they’ve added up to a slower and weaker La Niña development. That said, many of our models are holding steady for La Niña to develop shortly.

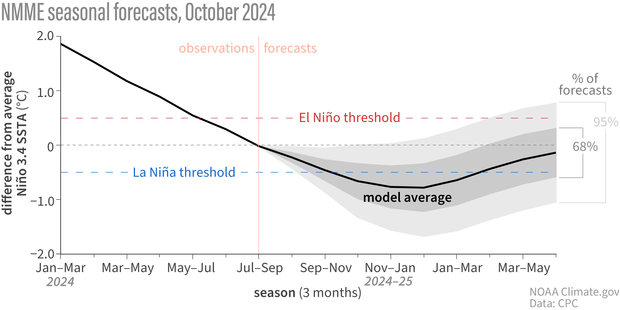

Line graph showing observed and predicted temperatures (black line) in the key ENSO-monitoring region of the tropical Pacific from early 2024 though spring 2025. The gray shading shows the range of temperatures predicted by individual models that are part of the North American Multi Model Ensemble (NMME, for short). Most of the shading appears below the dashed blue line by the fall, meaning most models predict that temperature in the Niño-3.4 region of the tropical Pacific will be cooler than average by at least 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 degrees Fahrenheit)—the La Niña threshold. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on data provided by Climate Prediction Center.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary

Forecasters have nudged the overall chance that La Niña will develop down a bit from last month, though. That means that, while La Niña is still favored, we’re less confident in La Niña emerging.

Out of the three climate possibilities—La Niña, El Niño, and neutral—forecasts say that La Niña conditions are the most likely for the September–November season (blue bar over the SON label, 60% chance). NOAA Climate Prediction Center image.

Also, if La Niña forms, it’s very likely this will be a weak event, with a maximum between -0.9 and -0.5 °C, in line with model predictions. In the historical record, which starts in 1950, only four La Niña events have formed this late in the year, with two forming in September–November and two in October–December. These were all either weak or on the border between weak and moderate. ENSO events are strongest in the winter, so there’s less time for this La Niña to grow from where we are now.

The strength of an ENSO event, as gauged by its sea surface temperature departures, matters because stronger events change the atmospheric circulation more consistently, leading to more consistent impacts on temperature, rainfall, and other patterns. A weaker event makes it more likely that other weather and climate phenomena could play the role of spoiler. However, even a weak La Niña can factor into seasonal outlooks, because it can still nudge the global atmosphere.

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer

Next month, Nat will review what the models have to say about winter conditions, including how much they reflect La Niña’s expected impacts. Stay tuned here at the ENSO Blog—we’re all treat, no trick!

Footnote

- The weekly SST data has been temporarily changed from OISSTv2.1 to UK Met OSTIA: https://ghrsst-pp.metoffice.gov.uk/ostiawebsite/index.html .

- ERSSTv5 has temporarily been replaced with JMA COBE2 SST data. https://ds.data.jma.go.jp/tcc/tcc/products/elnino/cobesst2_doc.html

- More on our usual temperature data in Tom’s post here.

Comments

Cause of ENSO

In a recent Yale CC article "Schmidt says that scientists still can’t explain the unexpected spike in temperatures. When I talked with him recently, he called the continuing confusion “a little embarrassing” for researchers."

A spike that lasts a year or more is not consistent with the secular, monotonic rise in temperature predicted by a GHG model. It could be a tipping point perhaps, but if the spike disappears, that does not make sense. So that leaves an El Nino or ocean-cycle cause, Hunga-Tonga response, or an aerosol change as has been suggested. No way is it a sunspot-related event IMO. As Gavin said, it's somewhat embarrassing not understanding the cause, but that's really in the context of not having a consensus to the cause of El Nino events in the first place. Or having an agreement of whether the AMO is an oscillation or not.

It's good that Gavin Schmidt is honest in his appraisal of the difficulty in pinning this all down.

global heat

Nature certainly can humble us in many ways, and the climate system often throws us curveballs (so it's not just for us ENSO forecasters and researchers). I agree that the magnitude of recent heat is still a mystery, but I disagree with the statement that "A spike that lasts a year or more is not consistent with the secular, monotonic rise in temperature predicted by a GHG model." The rise of global mean temperatures in response to GHG forcing does not preclude the competing or reinforcing effects of internal variability or other radiative forcing agents, which could last days or decades. So, I agree that it's unsettling that we don't have a definitive answer for this spike, but that shortcoming doesn't necessarily say anything about consistency or inconsistency with the influence of GHG forcing on global mean temperature.

Global heat

Noticed that in the interview article not one mention of the words CO2, GHG, greenhouse gas, climate change, or global warming as a mechanism for the conspicuous heat spike of the last 2 years. This could be overlooked by the author of the article, but the implication conveyed by Gavin Schmidt is that they're looking at something else, including ENSO. Yet it's not ENSO alone as observed with the large spikes in the AMO for the Atlantic and the IOD for the Indian ocean.

Central Based la Nina

Enjoy the updates as always Emily, thanks!

I've read on the past here that central based la Nina events are more common with weak events. At least currently looking at the SST maps the coldest SST locations are in the central Pacific. At least following SST graphs and the maps not much cold SSTs in the Nino 3 region. What do you think the odds are of a Central Based Modoki type La Nina?

Modoki

I cannot speak for Emily, but I can respond anyway. :-) The relationship between ENSO strength and east versus central/Modoki is stronger for El Nino than for La Nina. La Nina tends to be centered farther west than El Nino in general, so most La Ninas are "Modoki-like" to some extent (see this previous blog post). That said, it's still possible this event could be centered farther east or west than normal. I've been more focused on trying to nail down the intensity of this even that I haven't focused so much on the spatial "flavor." If I reach any new insights, I'll let you know.

La Nina

Thanks Nathaniel!

It seems the last several La Ninas were east based with colder Temps in the Nino 3 and Nino 1.2 regions.

different data

why have copernicus and noah as well as the UAH presented different numbers for global average temps for the last 3 months?

global temperature

The different temperature datasets have differences in data sources and methods for filling in data gaps, and they often report their global mean changes with respect to different base periods. These differences in data/methods can lead to differences in global average temperature, but these differences are usually pretty small. To me, it looks like the global average temperature is pretty consistent among datasets, although there are small differences (like UAH had September 2024 as the warmest and ERA5 had it as the second warmest). Those differences look like they are within the typical range of uncertainty, but if I'm missing something, or if you noticed differences that look unusually large, please feel free to clarify.

Weather Nerds Unite

I just came here to say that I didn't know this blog existed, and I'm so happy it does. I love when scientists convey information so that even the layperson can understand - it helps me from losing my intro to environmental science knowledge from college!! The data visualizations are great. Thank you for your work and the creativity you put into this!

proud nerd

Thanks so much, Els! We're glad you're here. I certainly appreciate everything the rest of the team does, and I don't hesitate to borrow a lot of these visuals for my presentations.

Bring in the science communicators

Lead with your results. Low confidence in La Nina at this point. But it may change dramatically soon. Stay tuned.

Appreciate the literary subtitles. But it too way too long to get to the point.

So, read Randy Olson's "Don't be such a scientist." Then, bring him in as a consultant. Or, take my winter course on Environmental Research and Communication.

Professor Abel

Re: Bring in the...

We respect feedback from our fans and our critics, so thanks for taking the time to share your opinion. We do try to balance providing a "straight to the point" perspective for casual readers with the sorts of additional detail and insight that our regular readers come here for. Honestly, I can't help but wonder if you missed the intro, since our blogger pretty much did what you suggest!

Commentary on the recent global temperature spike

My recent YouTube commentary on the recent anomalously large spike (step) in global average surface temperatures might be of some interest to blog readers. The link for the video is: https://youtu.be/-EVy7MkUDBg

I'll be posting an update on the temperatue spike vs step issue shortly.

Add new comment