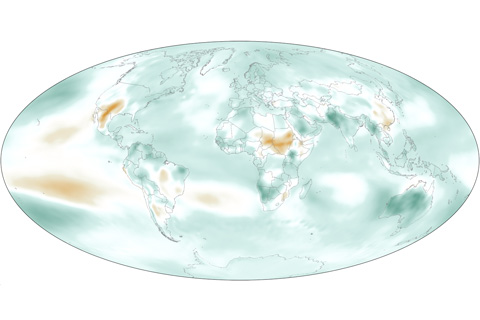

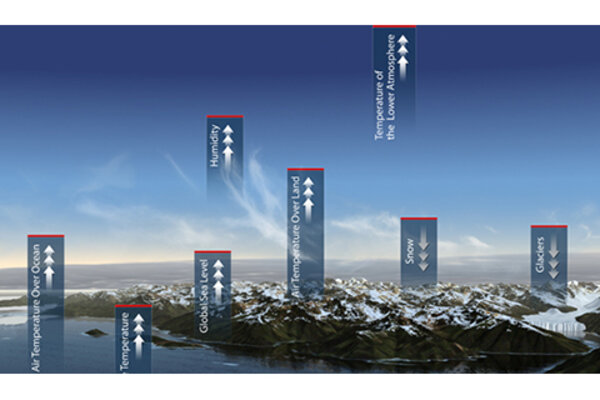

In 2011, Earth’s atmosphere was cooler and drier than it had been the previous year, but it was more humid than the long-term average.

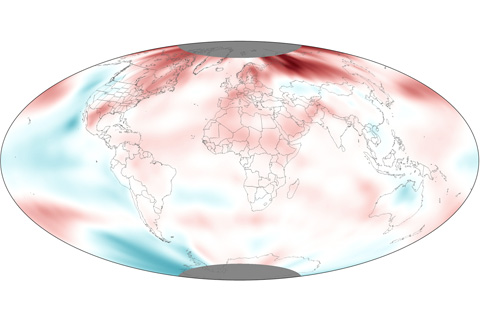

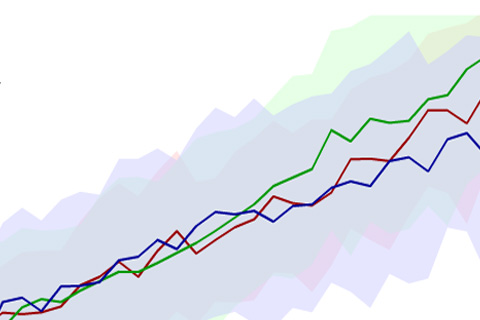

Despite the double-dip La Nina that occurred throughout the year, 2011 was still among the 15 warmest years on record. Including the 2011 temperature, the rate of warming since 1971 is now between 0.14° and 0.17° Celsius per decade (0.25°-0.31° Fahrenheit), and 0.71-0.77° Celsius per century (1.28°-1.39° F) since 1901.

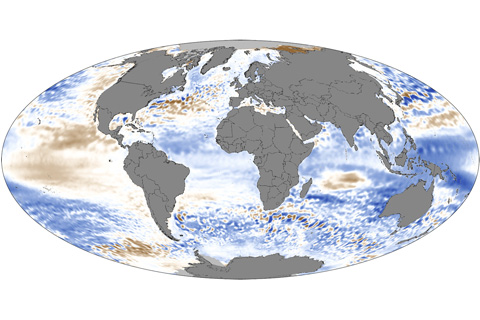

In 2011, global sea levels fell below the long-term trend of sea level rise, but as La Niña waned late in the year, global ocean levels began rising rapidly.

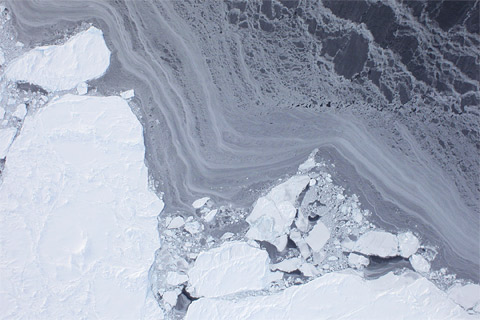

NOAA scientists have documented a new impact of the increasingly thin blanket of Arctic sea ice: gases escaping from the thinner ice in spring are affecting air chemistry, reducing ground-level ozone, and likely increasing mercury contamination.

In the Great Lakes region, conservation and resource managers are already fending off attacks by multiple invasive species. In the future, climate change will present new challenges, such as anticipating the invaders’ next move and dealing with new, emerging threats — some of which could be swimming around in your aquarium right now.

It is virtually certain our world will continue to warm over this century and beyond. The exact amount of warming that will occur in the coming century depends largely on the energy choices that we make now and in the next few decades.

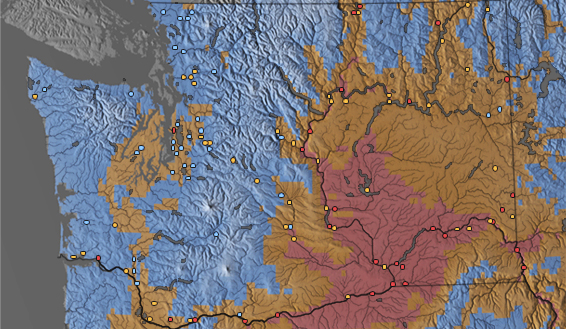

Modeling predicts that increasing greenhouse gas emissions will significantly increase thermal stress on Pacific Northwest salmon in coming decades, making the hard job of restoring endangered wild salmon even harder.

Climate Science 101: What is the Difference Between Weather and Climate?

February 15, 2012

Climate Science 101: Historical Perspectives on Climate Change

February 15, 2012

Climate Science 101: The State of the Climate in 2009

February 15, 2012