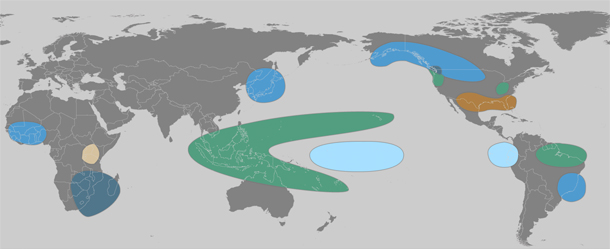

The lead character in the 2011 climate story was La Niña—the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation—which chilled the central and eastern tropical Pacific at both the start and the end of the year. These natural cooling events have a long reach: many of the big climate events of 2011, including famine-inducing drought in East Africa, an above-average hurricane season in the Atlantic, and record rainfall in many parts of Australia, are common “side effects” of La Niña.

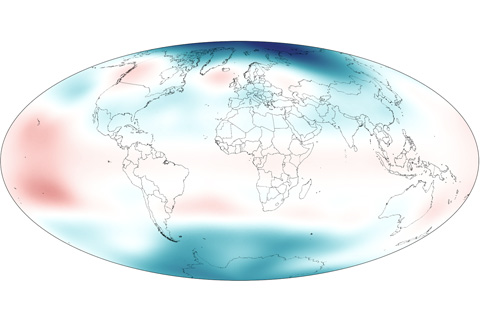

In early 2011, stratospheric temperatures rose over the tropics due to La Nina while temperatures over the poles fell below the long-term average.

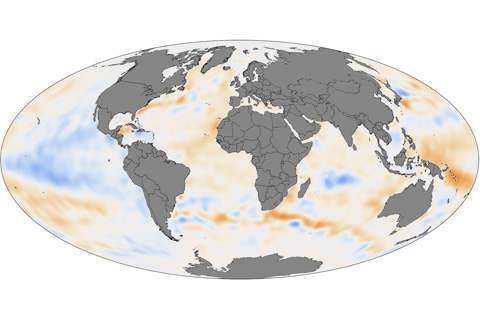

Except for some La Niña-cooled regions of the tropical Pacific and a few other cool spots, the upper ocean held more heat than average in 2011 in the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, and Southern Oceans.

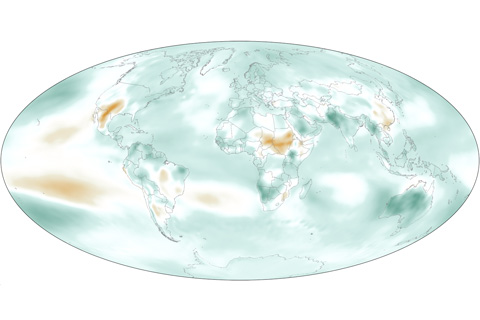

In 2011, Earth’s atmosphere was cooler and drier than it had been the previous year, but it was more humid than the long-term average.

Although solar flares can bombard Earth’s outermost atmosphere with tremendous amounts of energy, most of that energy is reflected back into space by the Earth’s magnetic field or radiated back to space as heat by the thermosphere.

Climate Science 101: What is the Difference Between Weather and Climate?

February 15, 2012

Climate Science 101: Historical Perspectives on Climate Change

February 15, 2012

The Arctic Report Card: Highlights from 2011

January 20, 2012