Another mild winter? NOAA’s 2018-19 winter outlook

The air is starting to feel crisp, the leaves are changing, and the aroma of pumpkin spice lattes are filling your favorite coffee shops. This can only mean one thing – it’s time for my annual post on NOAA’s expectations for the upcoming winter! And once again, one of the key players is found in the tropical Pacific. In contrast with the last two years, when we were looking at potential La Niña development, this year we’re waiting to see if El Niño will arrive in time to impact winter. Without further ado, let’s take a look at NOAA’s 2018-19 Winter Temperature and Precipitation Outlook and see how ENSO has affected this forecast.

As usual: Outlooks are probabilistic, so no guarantees

Wait, just one more thing before jumping to the outlooks. I again remind readers (if this seems repetitive, well, it is) that these forecasts are provided in terms of probabilities (% chance) for below, near, or above average outcomes with the maps showing only the most likely outcome (1). Because the probabilities on these and all CPC outlook maps are less than 100%, there is no guarantee you will see temperature or precipitation departures from normal that match the color on the map. As we’ve explained in earlier blog posts, even when one outcome is more likely than another, there is still always a chance that a less favored outcome will occur. And in fact, for the forecasts to be reliable (a critical part of a probabilistic forecast), less likely outcomes MUST happen from time to time.

Outlook for 2018/19 winter

Finally, the outlooks! Both the temperature and precipitation outlooks depend to a certain extent on typical El Niño impacts, but forecasters think a weak El Niño event is most likely. This means that despite the potential for El Niño, confidence in this outlook is less than we had than during recent strong events like in the winter of 2015/16 (more on confidence below).

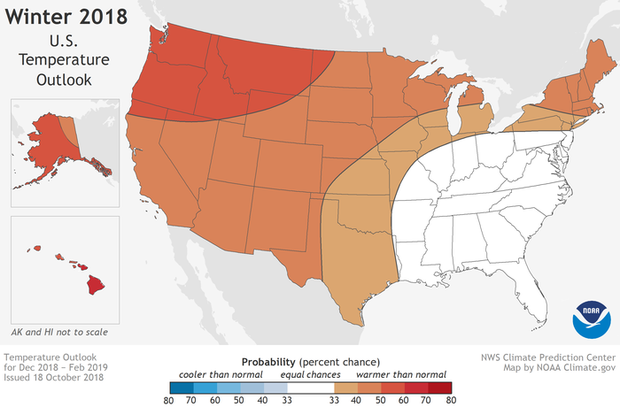

This lower confidence is reflected in fairly modest probabilities for the temperature outlook, with the largest probabilities only between 50-60% for above normal temperatures in Hawaii, Alaska, and parts of the Pacific Northwest and northern Rockies. The other shaded regions on the map indicate probabilities between 33-50%, meaning that the forecast only tilts modestly towards above normal temperatures. And while no areas of the country are favored to have below normal temperatures, it certainly wouldn’t be surprising for some areas to experience below normal temperatures this winter. This would be most likely in the white areas labeled EC (more on that later).

Places where the forecast odds favor a much colder than usual winter (blue colors) or much warmer than usual winter (red), or where the probability of a cold winter, a warm winter, or a near-normal winter are all equal (white). The darker the color, the stronger the chance of that outcome (not the bigger the departure from average). NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data from NOAA CPC.

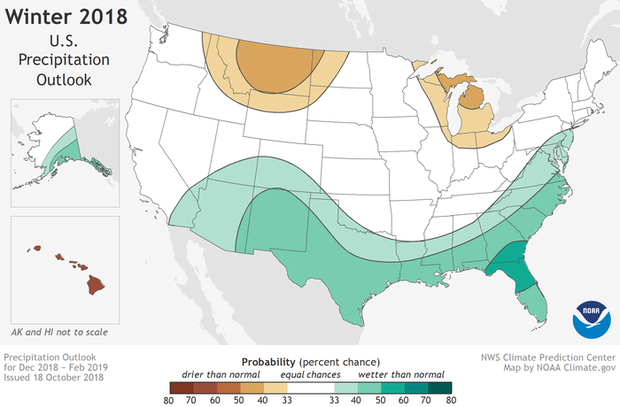

Similarly, the precipitation outlook is also much less confident (lower probabilities) than the forecast for the last El Niño winter. The pattern does resemble the typical precipitation pattern seen in an average El Niño, with above-average precipitation favored over much of the southern tier and southern Alaska, and with below-average precipitation most likely in the northern Rockies, around the Great Lakes and in Hawaii. However, the probabilities are much lower than typical for an El Niño winter, reflecting greater uncertainty over what may happen. A 50% chance is exceeded only in northern Florida and southern Georgia, and in Hawaii.

Places where the forecast odds favor a much drier than usual winter (brown colors) or much wetter than usual winter (blue-green), or where the probability of a dry winter, a wet winter, or a near-normal winter are all equal (white). The darker the color, the stronger the chance of that outcome (not the bigger the departure from average). NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data from NOAA CPC.

Both maps include blank regions where neither above-, nor near-, nor below-normal is favored. These areas (shown in white and labeled EC for “equal chances”), have the same chance for above-, near-, or below-normal (33.33%). This doesn’t mean that near-average temperature or precipitation is expected this winter in those regions, but rather that there’s no tilt in the odds toward any outcome. And as mentioned earlier, the blank region in the temperature map has the greatest chance of being colder than average this winter.

El Niño: Where’s the confidence?

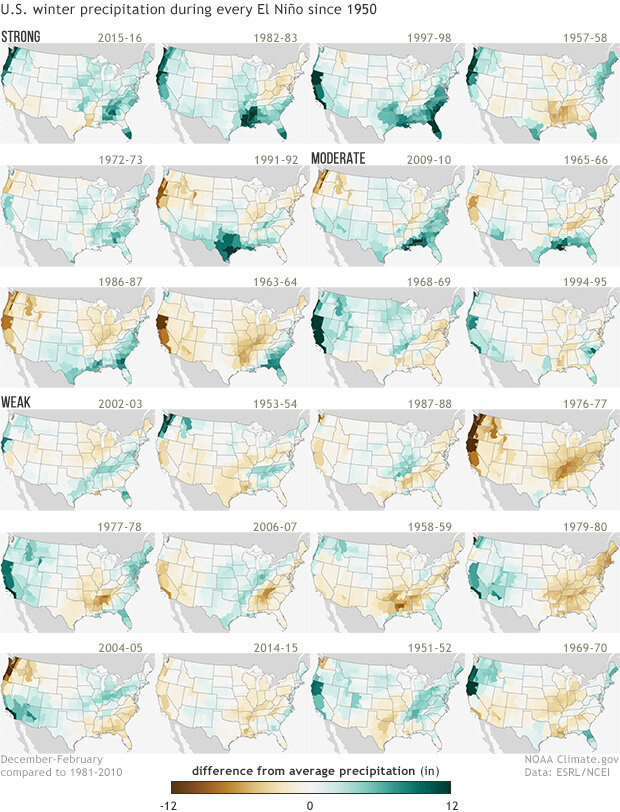

In two of my earliest posts for the ENSO Blog, I wrote about the relationship between El Niño and winter precipitation and temperature, presenting figures showing precipitation and temperature differences from average for the 20 prior El Niño episodes from 1950-2013. Here those figures are updated below to include events through the 2015/16 El Niño. An important theme emerges from these two figures: in terms of U.S. impacts, no two El Niño episodes are the same, and winter precipitation and temperature become less consistent as the strength of El Niño decreases.

This is especially true for precipitation, with the tendency for wetter seasons often dominating the southern part of the nation during the stronger episodes (maps towards the top of the figure), but drier winters occurring more frequently for the weaker episodes (bottom 12 maps). Thus, the precipitation outlook will be less confident during the weaker episodes.

Winter precipitation patterns during each of the El Niño episodes since 1950. Dark green colors indicate much wetter than normal conditions, and dark brown colors indicate much drier than normal conditions. The top row corresponds with the strongest El Niño episodes, the two rows below correspond with moderate El Niño episodes, and the bottom three rows correspond with weak El Niño episodes. Maps by NOAA Climate.gov, based on NCDC climate division data provided by the Physical Sciences Division at NOAA ESRL.

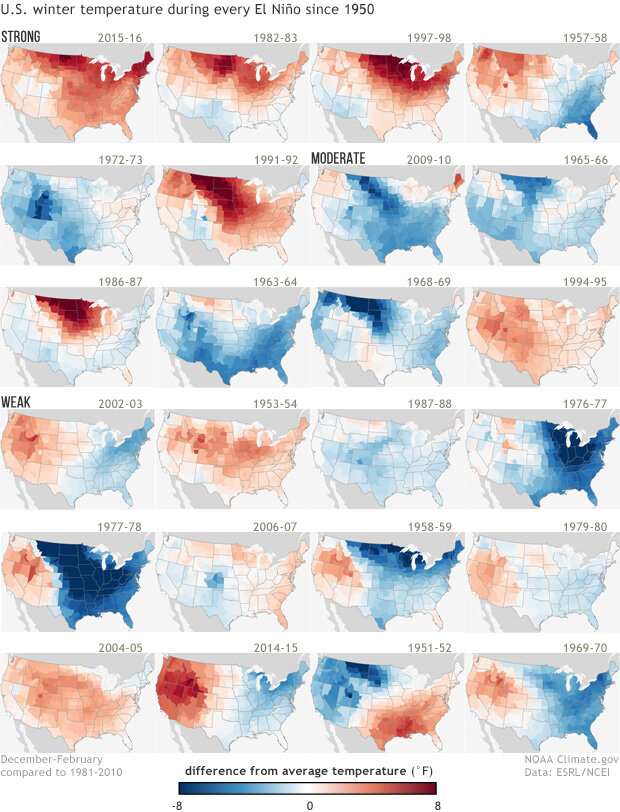

Temperature patterns over the U.S. (below) are not as well defined, with the El Niño winter-to-winter variability fairly large among the stronger events, although the 3 strongest events (1982-83, 1997-98, and 2015-16) were generally well above average coast to coast. However, some of the other stronger events (1972-73, 1965-66) were much colder, indicating that agreement even among the stronger episodes is lower. An average (not shown) of the 12 weakest events reveals some agreement favoring above average temperatures in the western and central states, but a more muddled picture in the East, where weak El Niño winter temperatures have varied widely from below-normal to above-normal. This East-West split may not be robust due to the small sample size, but it may also indicate that weak El Niño winters feature a typical temperature pattern that is somewhat distinct from the canonical pattern of a warmer-than-normal North and a normal or colder-than-normal South.

This lack of consistency reflects that a weaker El Niño does not exert a strong push (or forcing) on the U.S. If we have a stronger El Niño, the big push from the vigorous tropical heating sets off a cascade of global impacts, including changes in the strength and position of the jet stream that affects U.S. weather, which tends to dominate over other factors that could impact the outlook. Because of an expected smaller push from El Niño, however, other climate patterns are more likely to play a larger role in shaping the upcoming winter. These patterns, like the Arctic Oscillation and the Madden-Julian Oscillation, can have a profound impact on the character of the winter, but are quite challenging to predict months in advance.

Winter temperature patterns during each of the El Niño episodes since 1950. Dark red colors indicate much warmer than normal conditions, and dark blue colors indicate much colder than normal conditions. The top row corresponds with the strongest El Niño episodes, the two rows below correspond with moderate El Niño episodes, and the bottom three rows correspond with weak El Niño episodes. Maps by NOAA Climate.gov, based on NCDC climate division data provided by the Physical Sciences Division at NOAA ESRL.

The NOAA Climate Prediction Center (CPC) issues seasonal temperature and precipitation forecasts to help communities prepare for what's likely to come in the next few months. Empowering people with actionable forecasts and winter weather tips is key to NOAA’s effort to build a Weather-Ready Nation.

Lead Editor: Nat Johnson, NOAA GFDL

Footnotes

(1) The three categories are defined by terciles of the historical temperature or precipitation data, which are the 33.33 and 66.67 percentile positions in the distribution. In other words, they are the boundaries that subdivide the historical data into three equally populated categories (one-third of the data in each category): below-normal, near-normal and above-normal. In the maps, the CPC forecasts show the probability of the favored category only when there is a favored category; otherwise, they show EC (“equal chances”). Often, the near-normal category remains at 33.33%, and the category opposite the favored one is below 33.33% by the same amount that the favored category is above 33.33%. When the probability of the favored category becomes very large, such as 70% (which is very rare), the above rule for assigning the probabilities for the two non-favored categories becomes different.

Comments

Storm track

RE: Storm track

That's always the million dollar question and at this point, impossible to determine. We do see the best chance for cold (hence a dip in the jetstream) into the Southeast, Ohio Valley. and Mid-Atlantic, but whether that's associated with a suppressed jet stream that keeps most of the precipitation down to the South, or whether storms ride up the coast is an unknown at this time.

Re: Another mild winter?

RE: Re: Another mild winter?

The most reliable dry signal is really in the northern Rockies, with a weaker signal farther west. From the figure, you can see that's it's really a mixed bag, although the two most recent weak episodes did lean dry in much of the Pacific NW.

ENSO and crop production statistics

Link between ENSO and mild North American winters

RE: Link between ENSO and mild North American winters

It's certainly true that weaker events are not as robust in delivering a mild winter to North America. One thing to be cautious about, however, is that the colder years were generally earlier during the period of record. Almost all of the later years were warm out West, hence the tilt toward above normal temperatures in the region of the country. The East has been more of a coin flip, so the current outlook of equal chances fits with recent historical weak El Ninos.

Looking at those past El Nino

RE: Looking at those past El Nino

Good question... there are some papers looking at whether El Nino variability increases (vs. Neutral or La Nina winters), but in my view is there are some conflicting results. Also there is some pretty decent results showing that the variability doesn't change as much as the shift in *mean* anomalies (my colleagues paper here: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00382-014-2336-9 ). While the year-to-year pattern can be noisy, there is information to be gained by the average cahnge in temperature and precipitation. If you play your odds over the long term, then this skill becomes more evident. This is why we issue our outlooks as probabilities and not in inches or in degrees... b/c we know the event to event variations can be large.

RE: RE: Looking at those past El Nino

These maps are very clean

I like the style of your maps.

Where is the data for the maps?

Can you share where the data came from that was used to produce these maps? Is it on the NCEI site? Thanks.

Industrial Connection

Would there be a way to see this overlaid with maps of industrial sites across the US during each time period? That could make a compelling story!

7 subtropical storms in the

Virginia weather

Winter much better in 2019

Predictions

Add new comment